Biden’s executive order on AI is ambitious — and incomplete

- Share via

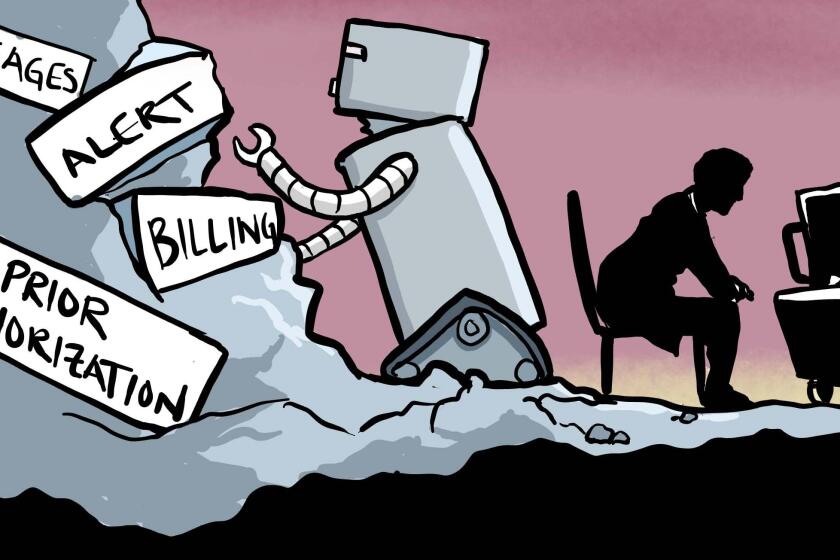

Last month President Biden issued an executive order on artificial intelligence, the government’s most ambitious attempt yet to set ground rules for this technology. The order focuses on establishing best practices and standards for AI models, seeking to constrain Silicon Valley’s propensity to release products before they’ve been fully tested — to “move fast and break things.”

But despite the order’s scope — it’s 111 pages and covers a range of issues including industry standards and civil rights — two glaring omissions may undermine its promise.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signaled he wants the state to lead the way when it comes to putting guardrails around AI’s potential risks.

The first is that the order fails to address the loophole provided by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. Much of the consternation surrounding AI has to do with the potential for deep fakes — convincing video, audio and image hoaxes — and misinformation. The order does include provisions for watermarking and labeling AI content so people at least know how it’s been generated. But what happens if the content is not labeled?

Much of the AI-generated content will be distributed on social media sites such as Instagram and X (formerly Twitter). The potential harm is frightening: Already there’s been a boom of deep fake nudes, including of teenage girls. Yet Section 230 protects platforms from liability for most content posted by third parties. If the platform has no liability for distributing AI-generated content, what incentive does it have to remove it, water-marked or not?

Imposing liability only on the producer of the AI content, rather than on the distributor, will be ineffective at curbing deep fakes and misinformation because the content producer may be hard to identify, out of jurisdictional bounds or unable to pay if found liable. Shielded by Section 230, the platform may continue to spread harmful content and may even receive revenue for it if it’s in the form of an ad.

A bipartisan bill sponsored by Sens. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) seeks to address this liability loophole by removing 230 immunity “for claims and charges related to generative artificial intelligence.” The proposed legislation does not, however, seem to resolve the question of how to apportion responsibility between the AI companies that generate the content and the platforms that host it.

AIs can spit out work in the style of any artist they were trained on — eliminating the need for anyone to hire that artist again.

The second worrisome omission from the AI order involves terms of service, the annoying fine print that plagues the internet and pops up with every download. Although most people hit “accept” without reading these terms, courts have held that they can be binding contracts. This is another liability loophole for companies that make AI products and services: They can unilaterally impose long and complex one-sided terms allowing illegal or unethical practices and then claim we have consented to them.

In this way, companies can bypass the standards and best practices set by advisory panels. Consider what happened with Web 2.0 (the explosion of user-generated content dominated by social media sites). Web tracking and data collection were ethically and legally dubious practices that contravened social and business norms. However, Facebook, Google and others could defend themselves by claiming that users “consented” to these intrusive practices when they clicked to accept the terms of service.

In the meantime, companies are releasing AI products to the public, some without adequate testing and encouraging consumers to try out their products for free. Consumers may not realize that their “free” use helps train these models and so their efforts are essentially unpaid labor. They also may not realize that they are giving up valuable rights and taking on legal liability.

Many physicians are burned out and rushed, so it’s no wonder if they fail to connect meaningfully with each patient. If a robot can help, why not?

For example, Open AI’s terms of service state that the services are provided “as is,” with no warranty, and that the user will “defend, indemnify, and hold harmless” Open AI from “any claims, losses, and expenses (including attorneys’ fees)” arising from use of the services. The terms also require the user to waive the right to a jury trial and class action lawsuit. Bad as such restrictions may seem, they are standard across the industry. Some companies even claim a broad license to user-generated AI content.

Biden’s AI order has largely been applauded for trying to strike a balance between protecting the public interest and innovation. But to give the provisions teeth, there must be enforcement mechanisms and the threat of lawsuits. The rules to be established under the order should expressly limit Section 230 immunity and include standards of compliance for platforms. These might include procedures for reviewing and taking down content, mechanisms to report issues both within the company and externally, and minimum response times from companies to external concerns. Furthermore, companies should not be allowed to use terms of service (or other forms of “consent”) to bypass industry standards and rules.

We should heed the hard lessons from the last two decades to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Self-regulation for Big Tech simply does not work, and broad immunity for profit-seeking corporations creates socially harmful incentives to grow at all costs. In the race to dominate the fiercely competitive AI space, companies are almost certain to prioritize growth and discount safety. Industry leaders have expressed support for guardrails, testing and standardization, but getting them to comply will require more than their good intentions — it will require legal liability.

Nancy Kim is a law professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.