Opinion: American Jews a century ago faced upheaval, bigotry and division — all familiar today

- Share via

The last month has been profoundly disorienting for American Jews, as we have absorbed the horrific Hamas massacre and subsequent Israeli counterstrikes. This terrible war has surfaced deep divisions within the Jewish community, with some supporting a cease-fire or expressing solidarity with Palestinian civilians and others calling for unwavering backing for the Israeli government.

Yet many of us are experiencing the same jarring feeling that our traumatic past is not so distant, that dormant bigotries have been reawakened and that the Jewish people have again arrived at a moment of profound upheaval.

More than a century ago, American Jews believed they were on the cusp of a new era, that they had finally found sanctuary in a world that for millennia had provided no quarter. Then they too faced a crisis that was both far away and also at their doorstep.

The current wave of violence targeting Arabs, Muslims and Jewish people is part of a disturbing upswell of intolerance in the United States. The best way to fight it is to call it out.

Between 1880 and 1910, more than 1.5 million Jews poured into the United States, many fleeing antisemitism and oppression in Russia and its environs. They settled in large numbers in New York, gravitating toward Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where Jewish immigrants crowded into dilapidated tenements that lacked electricity and plumbing and were so closely packed that natural light and ventilation were luxuries.

The demographic changes that came with large-scale immigration prompted an upsurge of nativism. Groups such as the Immigration Restriction League, founded by Harvard alums, emerged to beat back the flood of foreigners, contending they imported disease, crime and moral decay; stole American jobs; and burdened public resources.

Jacob Schiff, the legendary financier considered the leader of American Jewry during that period, watched this trend with alarm. He represented a wealthy German Jewish elite who had come to the U.S. decades earlier. Many of them hailed from modest origins, rising from peddling to the corridors of finance and commerce. None had ascended higher than Schiff, who now dominated their community’s philanthropic life.

Beginning in the 1880s, as pogroms erupted in Russia and conditions for Jews worsened, Schiff and his allies had fended off attempts to curb immigration, including efforts to impose literacy requirements. They had established a sprawling network of charitable organizations to assist the new arrivals and speed their acculturation. But in the early 1900s, as Russian and Eastern European refugees flooded into the country, even this robust aid apparatus was straining under the demand. Schiff believed New York could no longer absorb the deluge and worried that the crime and squalor of the Lower East Side would both provide ammo to the restrictionists and fuel antisemitism, which was already on the rise.

College officials may fear being perceived as taking sides in the Israel-Hamas conflict, but it is wrong to confuse condemning antisemitism with ignoring the plight of the Palestinians.

Public opinion, meanwhile, was shifting sharply toward restriction. During his annual address to Congress in December 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt stated: “The laws now existing for the exclusion of undesirable immigrants should be strengthened.”

The solution, Schiff believed, was not halting immigration — but diverting it, in line with Roosevelt’s suggestion that the “right kind of immigration” should be directed “away from the congested tenement-house districts of the great cities.”

By August 1906, Schiff was sketching out his plan in a letter to British author and activist Israel Zangwill, the son of Russian immigrants and an acolyte of Theodor Herzl, the father of Zionism. Zangwill had broken with the Zionist movement following its leader’s 1904 death, forming an organization called the Jewish Territorial Organization. Where Zionists were pushing to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine — to the exclusion of other options — Zangwill and his organization were open to exploring alternative territories for the mass settlement of Jewish immigrants.

Proud of his American citizenship, Schiff found Jewish nationalism distasteful, if not dangerous. “Political Zionism places a lien upon citizenship” and “creates a separateness that is fatal,” he had said. Many American Jews during that era shared his viewpoint.

But Schiff was willing to set aside his philosophical differences with Zangwill for help in routing immigration away from New York. Schiff initially favored New Orleans as the port for diverted immigrants, but he and his compatriots settled on Galveston, Texas, because it was farther west and not a major city where immigrants would be tempted to settle. It could serve not as a destination but as a transfer point to locales west of the Mississippi.

An immigration group Schiff helped found would work with Zangwill’s organization to convey Jewish immigrants to Germany and then to Galveston. The new arrivals would receive some money and be sent on to one of 19 cities — including Des Moines, Denver and Kansas City — where local committees had formed to sponsor the immigrants and place them in jobs.

Advocacy groups are tracking increased discrimination and attacks against Arabs, Palestinians and Muslims in the U.S. as the death toll in Gaza mounts.

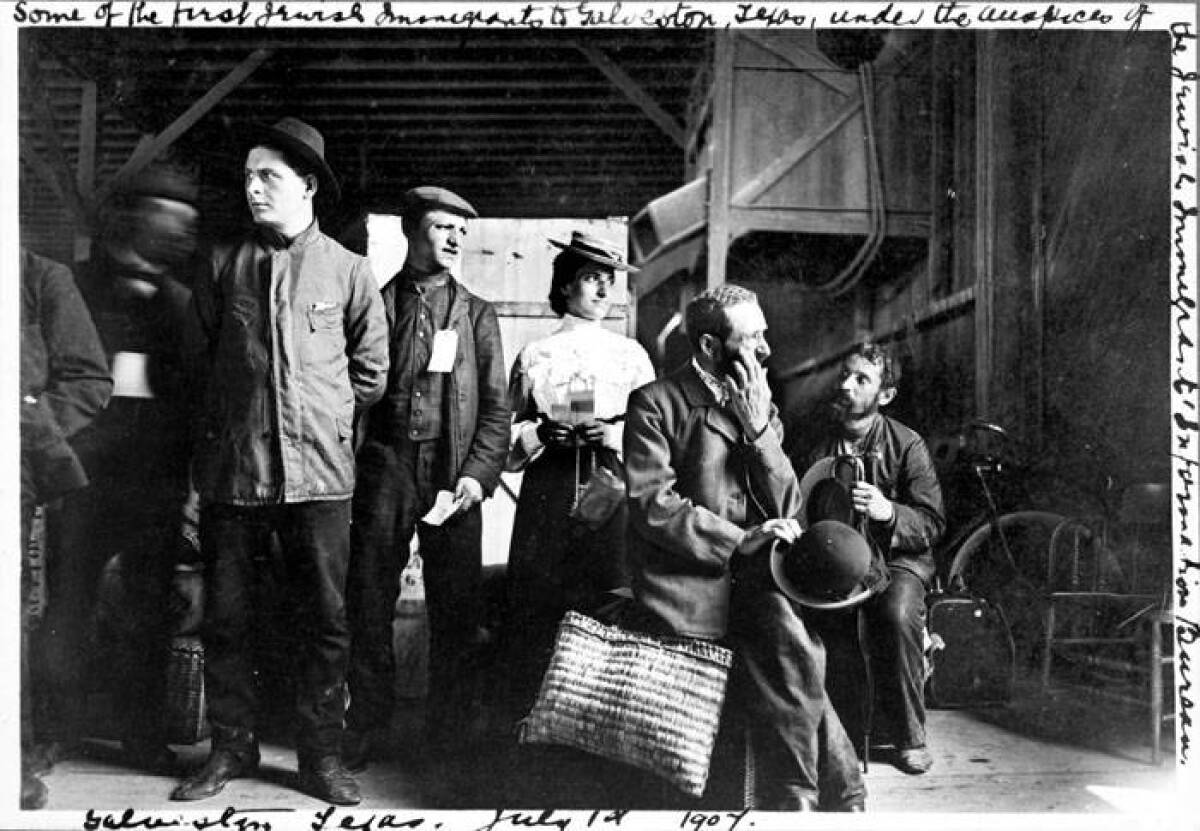

On July 1, 1907, the first group of Jewish refugees reached Galveston. One by one the 87 immigrants were examined by a doctor, grilled by inspectors and scrutinized by customs officers. By the end of the year, 900 immigrants had passed through the port. But soon the Panic of 1907 and the recession that followed made it difficult to find jobs for the newcomers. The flow of Russian immigrants, via Galveston, slowed to a trickle.

While Schiff’s Galveston project flailed and the economy wallowed, a new but related crisis struck that threatened to tarnish perceptions of Jews.

On Sept. 1, 1908, New York Police Commissioner Theodore Bingham published a treatise titled “Foreign Criminals in New York” that included the shocking — and false — claim that Jews comprised 50% of the city’s criminal element. Bingham’s essay drew widespread condemnation, sparking fiery editorials from the Jewish dailies and protest meetings. Downtown leaders directed their fury not just at the commissioner but at the wealthy uptown Jews, Schiff in particular, who were slow to speak out against the article.

Soon Bingham retracted his comments, claiming that the statistics he cited were “unreliable.” The scandal faded, but in its wake resentments between uptown and downtown Jewish communities lingered.

Outside of New York, a change in administrations doomed the struggling Galveston movement, with President Taft’s administration less supportive than Roosevelt’s. By 1909, many of the Jewish immigrants who arrived at Galveston were turned back. Schiff’s project, hobbled by its stop-and-start nature and plagued by internal squabbling among its partners, shut down in 1914. In seven years, the initiative settled some 10,000 Jewish refugees, less than half of the 25,000 immigrants Schiff hoped to support.

Soon, the immigration restrictions the Galveston movement sought to avert all but sealed the nation to refugees for decades to come. As Schiff’s project collapsed, and the U.S. was no longer a viable safe haven for Jewish immigrants, Zionism gained ground in Europe and the U.S. In the wake of the 1917 Balfour Declaration declaring British support for a Jewish homeland, the movement’s dream, once far-fetched, began to come to fruition, though skirmishes between Zionists and non-Zionists would continue for decades.

Now, the anxieties and divisions of a century ago feel oddly familiar. Again our communities see how, despite our differences, we are often painted with the same brush; how easily medieval prejudices can become a modern concern; and how what happens overseas can have ramifications in Indiana or New York or California.

Daniel Schulman is the deputy Washington, D.C., bureau chief of Mother Jones. His book “The Money Kings: The Epic Story of the Jewish Immigrants Who Transformed Wall Street and Shaped Modern America,” from which this piece is adapted, publishes on Nov. 14.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.