Editorial: Voters said no to ending money bail in 2020. Why is L.A. County doing it anyway?

In 2018, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill into law to end cash bail in California permanently. But cash bail is still with us. What gives?

The bail bond industry led a signature-gathering campaign to send the measure to voters as a referendum. When it qualified for the ballot, Senate Bill 10 â by then-Sen. Bob Hertzberg (D-Van Nuys) incorporating a bill by then-Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Alameda), now state attorney general â was put on hold.

The referendum was part of the Nov. 3, 2020, ballot as Proposition 25. It was imperfect, but The Times editorial board supported it as a rare opportunity to finally be rid of cash bail: âThere is something repugnant, and corrosive to our collective notion of justice, about allowing people without money to stay locked up in jail while others, accused of the same crimes but with money to spend, can buy their way out. Thatâs bail in a nutshell.â

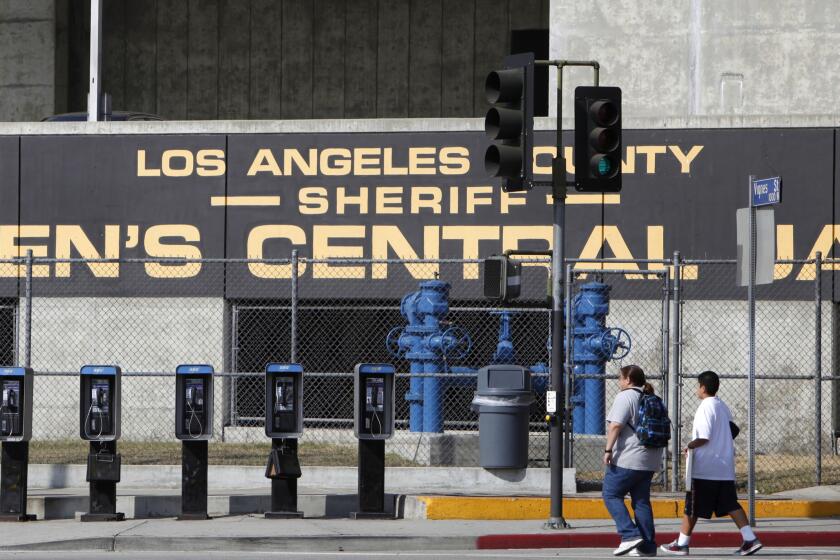

On Oct. 1 Los Angeles County transitions to a new way of administering pre-arraignment justice that doesnât use cash bail for most crimes.

But California voters defeated the measure, with 56.4% voting âno.â

That vote looms in the background today as the Los Angeles County Superior Court prepares to launch a program Sunday that sharply limits the use of cash bail and incarceration between arrest and a suspectâs first hearing, or arraignment, a few days later.

Why is eliminating money bail still an issue when the voters said ânoâ nearly three years ago?

The answer is that voters rejected one particular bail reform proposal, but not all possible bail reforms.

L.A. officials knew the bail schedules they used to lock people up before trial were unjust, but they didnât act. Now a ruling will force them to do so.

Hertzbergâs bill ending cash bail in California was opposed by the bail industry for obvious reasons. It would have put the industry out of business in the nationâs largest market.

Law enforcement, led by the California Peace Officersâ Assn., also opposed the elimination of money bail. Police argued that once they arrest a suspect, the person should be either locked up while awaiting trial to prevent further crimes, or have some money at stake. Some bail reformers also opposed the bill, arguing that it would leave too many people ineligible for release before arraignment, and that they could end up waiting in jail for as much as two weeks â far longer than under the money bail system.

Was the measure defeated by voters who wanted less bail reform, or more? Itâs impossible to know. Voters just vote âyesâ or âno,â without registering their reasons.

The Los Angeles Superior Court is wiping out money bail for many crimes. Evidence shows this makes the public safer, but people who should know better are likely to offer fact-free commentary about the change.

The L.A. County Superior Court is scaling back cash bail, but it was outclassed by the Illinois Supreme Court, which upheld legislation halting it altogether.

The referendum format may have confused some voters. A referendum that is successful stops a law from taking effect, but, counterintuitively, voters must choose ânoâ to signal their support of the repeal.

The same political dynamic that stopped bail reform three years ago exists to some extent today. The bail industry and law enforcement are unhappy with the L.A. County Superior Court program for releasing too many people without bail, because it cuts into their profits. Reform advocates are skeptical because the county program retains money bail and pretrial incarceration for many people accused of more serious crimes. Some also argue that there remain too many unanswered questions about the services and supervision that will be provided to people who are freed before arraignment.

The court is restricting cash bail because it treats suspects differently depending on whether they have money to buy their way out of jail, and because jail too often amounts to punishment before conviction. The court is also responding to numerous studies that show cash bail fails to do the two things it is intended to do: get defendants to return to court, and deter them from committing new crimes in the interim.

But the courtâs program will operate only in Los Angeles County, so the stakes are smaller. Police have persuaded court leaders to make it easier for law enforcement to hold people whom they believe are dangerous. Weâre hoping bail reform advocates wonât make the perfect the enemy of the good, and will work to improve the new program rather than block it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.