Opinion: California can lead the nation with a public option for health insurance. We have the data to show it works

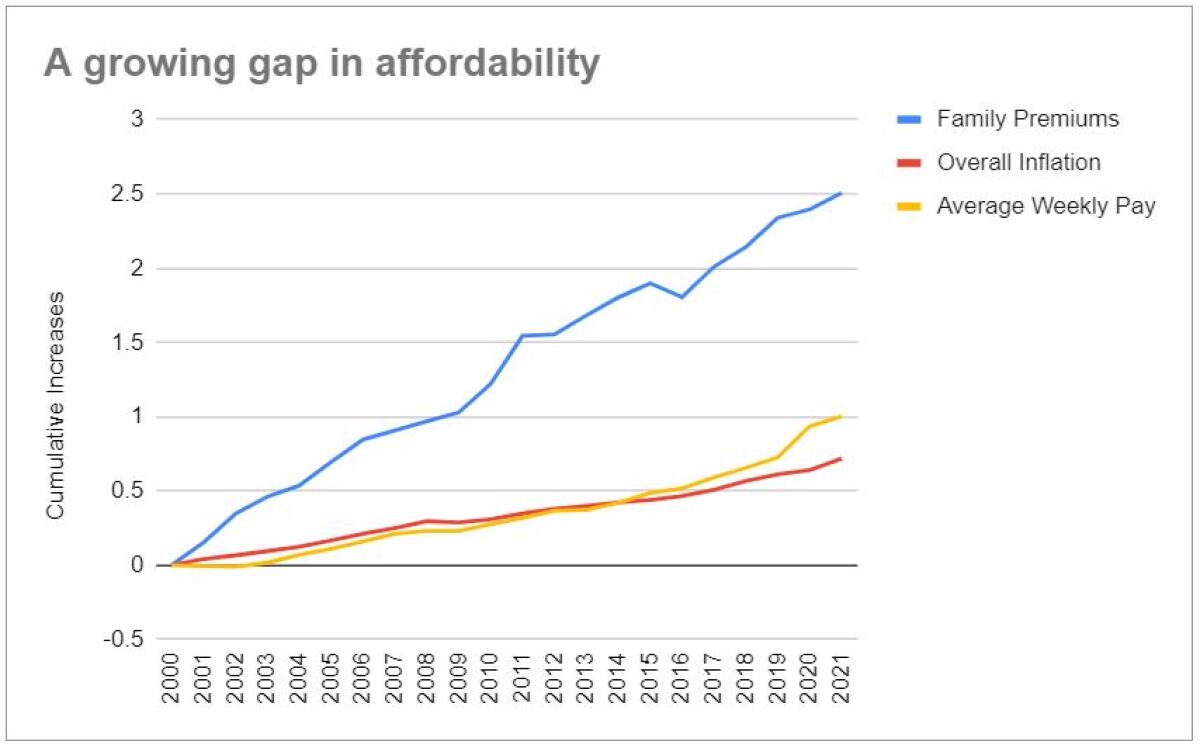

Californiaās workers are facing a mounting healthcare affordability crisis. The cost of insurance for families has grown more than two and half times faster than wages have, putting healthcare out of reach for more and more people. This gap is even larger for the stateās Black and Latino populations.

Part of the solution is within reach: The state should introduce a public option to compete with private insurance plans and drive down premiums. California is uniquely suited to pioneer this approach and has hard evidence that it will work.

President Biden proposed a public-option health insurance plan to increase competition and lower costs, but the gridlock in Washington and the lack of congressional support has shifted the development of a public option to the states, the ālaboratories of democracy.ā Washington has implemented one, with little success to date in gaining enrollment or lowering premiums.

We propose a public-option for California that we call Golden Choice, which would take a different approach. It is based on the ability of the stateās integrated medical groups to provide high-quality care at a lower cost by receiving monthly revenue per enrollee, a payment system known as capitation. The figure would be adjusted for each patientās age, gender, health status and related characteristics likely to influence need for care. This model provides incentives to the healthcare system to keep participants healthy and to manage illnesses with strong primary care and close coordination with specialists.

Our research indicates that health insurance premiums based on this model of care would be the lowest premiums in 14 of the 19 regions for Californiaās insurance marketplace. Individuals who switch from whatās now their most affordable option would save $1,389 a year on premiums through the state public option plan. Our work also looked at how the public option would fare if offered by the California Public Employees Retirement System, and we found that the premium would be lower than the premiums in 9 of the 10 HMO plans now offered to members.

California already has some experience with a public option: L.A. Care in Los Angeles County. This county-based public plan has been listed since 2014 on the stateās insurance exchange. Our research team found that L.A. Careās low premiums have had a competitive effect on the market, driving down prices. Premiums of the other plans have declined, and L.A. Careās enrollment increased to more than 125,000 last year. The estimated savings because of this public option were $345 million as of 2022. This decline in premiums did not happen in the rest of the state, where there is no similar plan. (L.A. Care has been faulted for treatment delays, but it says the problems reflect a systemic issue related to payment rates.)

In 2024, Inland Empire Health Plan, another county-based plan, is set to enter the Riverside/San Bernardino region with the lowest premium.

County plans are a valuable force in the marketplace, but the Newsom administration has the chance to make insurance more affordable on a much larger scale across all of California. Itās an achievable goal.

A statewide public option would require little to no new funding from the state. The Department of Managed Health Care already regulates capitated medical groups. We recommend that the state establish an Office of Public Options so that the 18 million commercially insured Californians and the uninsured are able to share the benefits of a public option ā particularly lower premiums. The office would organize, implement and promote a statewide public option.

The Newsom administration has the evidence that it needs to move forward. Such an initiative would be consistent with what the governor has done to address the increasing cost of prescription drugs by having the state partner with the private sector to develop drugs to compete in the marketplace.

The affordability of healthcare continues to be a nightmare for many Californians, fueling a crisis of medical debt that disproportionately hurts low-income workers and minorities. By introducing a state public plan, California would set an example for other states and the federal government to develop plans of their own that could, in turn, drive down premiums nationwide.

Richard Scheffler is a distinguished professor at the Graduate School of Public Health and the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley. He was appointed by the governor to serve on the Healthy California for All commission. Stephen Shortell is a distinguished professor at the School of Public Health and the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley and dean emeritus of the School of Public Health.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.