Opinion: Angry about the Supreme Court? Blame Congress

- Share via

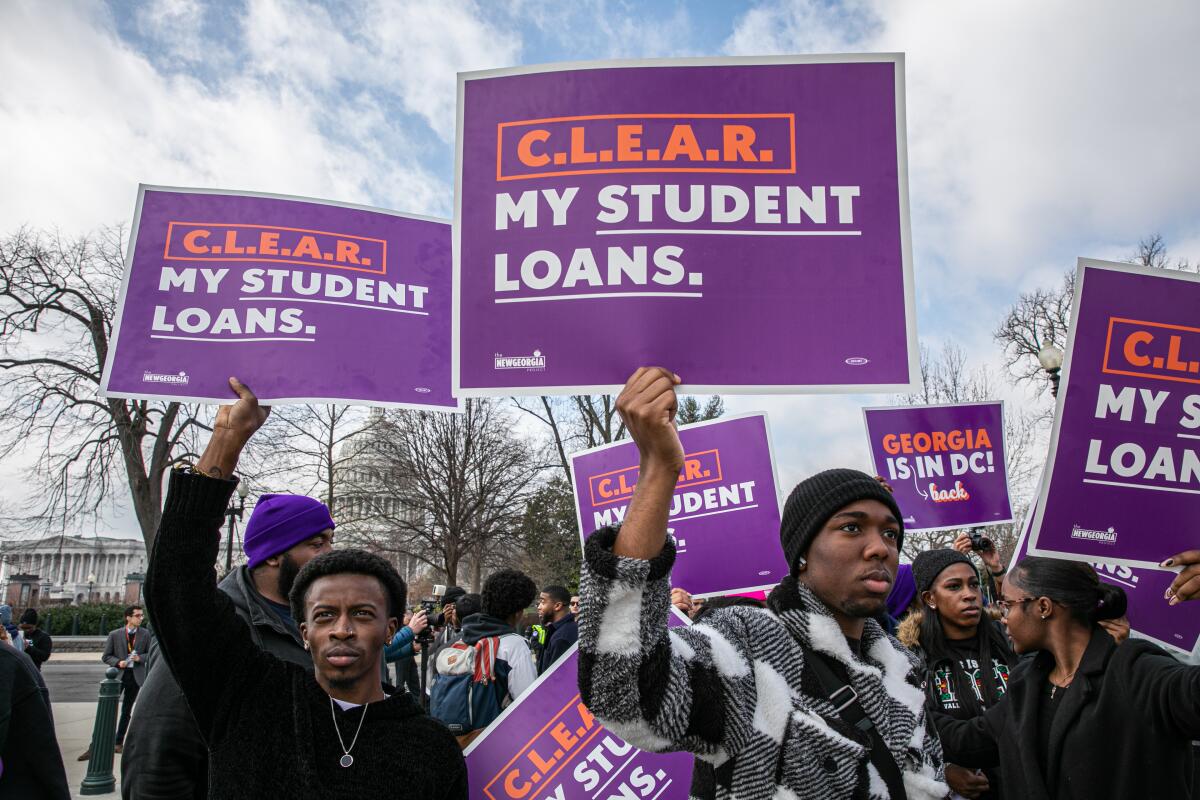

The Supreme Court is seizing more and more policymaking power, prompting a barrage of criticism for the court’s imperial tendencies. The current ultra-conservative super-majority is voraciously advancing a deregulatory and anti-democratic policy agenda, including by rolling back environmental protections, degrading bodily autonomy, invalidating common sense gun control, undermining labor rights, nullifying student loan forgiveness, gutting public health measures, eroding the administrative state, insulating public corruption and dismantling laws and policies aimed at promoting a multi-racial, pluralistic democracy. No doubt, the critics are right: The court is overreaching.

Yet prevailing criticisms miss half the problem. The court’s overreach is a direct result of Congress’ underreach. The Constitution relies on a system of checks and balances to preclude tyranny and ward off imperial overreach. As its framers recognized, power abhors a vacuum. The American model of government is not one of voluntary self-restraint but of countervailing power. It requires strong institutions vying against one another to prevent the concentration and abuse of power. It does not do well when a branch is content — even eager — to cede power and retreat from its constitutional role.

For decades, however, Congress has done just this. It has under-reached, under-performed and under-protected its legislative prerogative. This willing retreat has enabled an anti-democratic juristocracy. How?

When the justices didn’t gut the Voting Rights Act, people cheered. The ripple effect got less play — it may allow Democrats to retake the House in 2024

Congress has constrained its own legislative capacity while simultaneously neglecting its oversight role. The resulting power vacuum invited Supreme Court overreach, making the court’s imperial problem largely a problem of Congress’ secession.

First, Congress has abdicated its constitutional role of legislating by pitifully tying its own hands in parliamentary red tape. It continues to maintain the filibuster, requiring 60 votes for ordinary legislation to pass the Senate. This archaic rule works as an instrument of obstruction, allowing a single senator to grind legislation to a halt and effectively transforming the Senate into a “dadaist nightmare,” as a column in the New York Times called it.

The Senate also continues the farcical blue slip tradition, which grants individual senators veto power over federal judicial nominations in their states and thus impedes the majority party from filling judicial vacancies. Both houses further truncate members’ legislative and political power by tightly controlling when and by whom a vote is ever brought to the floor. Together, these procedural hurdles ensure gridlock, obscure accountability and neuter our legislature.

Second, Congress consistently neglects its duty to check the Supreme Court. It could but never has imposed any significant ethics framework on the court, even in the wake of a slew of improprieties involving multiple current justices. It meekly tolerates judicial snubs to its oversight powers, refusing to subpoena justices or private individuals involved in possible judicial corruption. Congress neglects to use its formidable budgetary powers over the Supreme Court, which allow it to control significant functions such as paying court staff, providing the justices’ security and keeping the lights on.

Strikingly, Congress has failed to even consider its far-reaching powers to restructure the court, such as by changing its size, imposing limits on how long the justices serve or redefining the court’s jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court didn’t rule that student debt can’t be forgiven; it merely said that government has to do it right or don’t do it at all.

As for its imagined role as a governing partner in dialogue with the judiciary, Congress has let the court dominate with a monologue. The justices have struck down constitutional precedents, such as the right to abortion, that the legislature has failed to codify. And Congress has failed to fulfill judicially imposed requirements that would make legislation pass constitutional muster — for example, it seemingly will not make a factual record that race discrimination continues to infect voting practices in order to reenact an important provision of the Voting Rights Act gutted by the court in 2013. Congress has also steadfastly shrunk from challenging the court’s overt incursions into its domain, for example by letting stand court decisions that erode the legislature’s power to create new rights for the public, including civil, environmental and privacy rights.

Congress’ abdication is not without reason; it reflects today’s perverse political incentives. A combination of political gerrymandering, voter suppression, extreme partisanship and unfettered campaign spending has made Congress all too happy to minimize its lawmaking function. It does not adequately use its legislative, override, confirmation and investigatory powers because a majority of its members no longer have the political incentive to do so.

Only Congress can claw back policymaking power from the Supreme Court. Doing so will not be easy, especially when both parties benefit from the anti-democratic power transfer to the judiciary. But there are immediate steps we can take.

It’s past time for Congress to abolish procedural barriers to legislating, including the filibuster, and support bold court reform strategies — which also need the backing of the president and public. Voters should support anti-gerrymandering initiatives at the state level and demand that congressional candidates in 2024 run on a platform of reining in the court and reforming Congress — two closely connected issues that garner immense popular support.

Congress’ appeasement and retreat are responsible for the belligerent court we have today. Instead of simply decrying the court’s overreach, we need to seriously address Congress’ underreach.

Francesca Procaccini is an assistant professor of law at Vanderbilt Law School. Nikolas Guggenberger is an assistant professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.