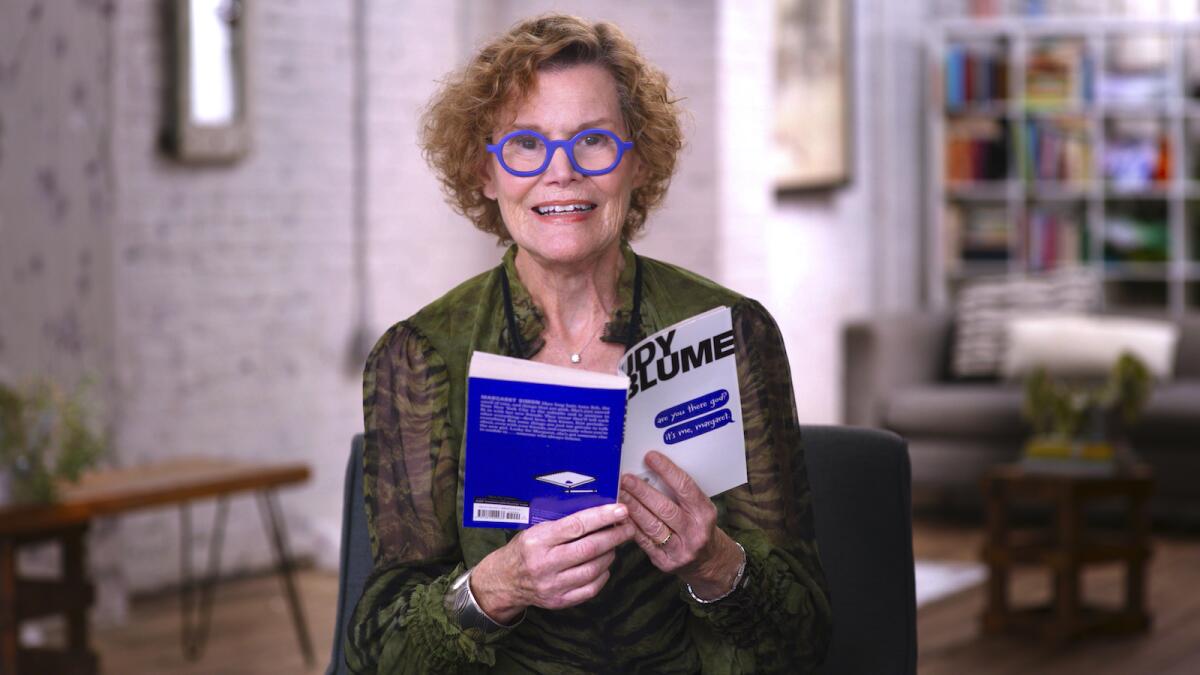

Column: Judy Blume and ‘Margaret’ are having a well-deserved moment

- Share via

Novelist Judy Blume and her straightforward depictions of menstruation, masturbation and teenage sexual desire came along a little too late for me.

By the time her groundbreaking 1970 novel “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” became popular, I was in high school and thought her books were for little kids. My friends and I, after all, had already passed around a dog-eared copy of Jacqueline Susann’s “Valley of the Dolls,” in junior high, so we were beyond fretting about when our periods would start and our boobs would pop. We wanted to read about the fraught lives of Hollywood’s pill-popping sexpots.

Which is why it took me so long to read Blume’s seminal work. Two years ago, I read it with my then-11-year-old niece, who lives with me. She was not interested in all the “our changing bodies” books I kept throwing at her. “Nope,” she’d say. “Not gonna happen to me.”

Maybe a good novel would help pierce the veil of her denial?

I’m not sure it did, but we did love the book, and we discovered, to our delight, that it delved into topics even deeper than the physiological changes of the adolescent female body.

“Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” was also — and maybe even mostly — a story about an 11-year-old girl caught between the two belief systems of her parents’ families: Christianity and Judaism. It was about a girl trying to decide whether God really exists, about her dismay upon learning that her mother’s Christian parents disowned their daughter for marrying a Jew. She puzzles over whether she should choose one religion over the other. “But if you aren’t any religion,” asks Margaret’s friend, “how are you going to know if you should join the Y or the Jewish Community Center?”

In her quest, Margaret attends temple with her grandmother, church services with friends and, unwittingly, confession at a Catholic church (which she flees when she realizes she has nothing to tell the priest).

It is not until the end of the book, when she spies blood in her undies, that she has an epiphany: “I know you’re there, God. I know you wouldn’t have missed this for anything! Thank you God. Thanks an awful lot.”

Ah, the perfectly rendered narcissism of youth.

In a case of great timing, one week before the movie version of “Margaret” hit theaters April 28, the documentary “Judy Blume Forever” was released on Prime Video. This is why you have probably been hearing and reading so much about Blume lately. Now 85, she is well overdue for this kind of attention.

After all, her professional trajectory perfectly recapitulates her times. A 1960s housewife raising two kids in suburban New Jersey, she was married to an attorney who “allowed” her to write as long as dinner was on the table when he got home from work.

When her first book made a splash, she says, other moms on her block resented her. As her popularity grew, her books came under fire for their frank approach to adolescent and teen life, and her marriage crumbled. She wanted more. So she kept writing, kept selling books, which kept getting banned. She divorced, remarried and divorced again before finding her soul mate.

The documentary includes many clips of Blume’s interviews over the years, including a 1984 appearance on the political show “Crossfire,” during which the conservative pundit Pat Buchanan accused her of being obsessed with sex.

“Deenie,” her 1973 novel in question, is about a teenage girl with scoliosis whose domineering mother wants her to be a model. At night, to relax and go to sleep, the stressed-out Deenie touches “her special place” and feels much better. That’s as explicit as Blume gets.

“Why can’t you write an interesting book for 10-year-olds without getting into a discussion about masturbation?” hectors Buchanan.

The generally soft-spoken Blume finally erupts: “Are you hung up about masturbation? One scene in one book!”

I can only think that this kind of attack, this kind of attention, has helped make Blume into one of the bestselling authors of all time: 90 million books sold, and counting.

As the young-adult historian and author Gabrielle Moss, one of many Blume fans interviewed in the documentary, quips: “Come for the female masturbation, stay for the empowerment.”

In 2017, Yale University acquired 50 years’ worth of Blume’s writings and correspondence. At one time, she was receiving between 1,000 and 2,000 letters a month. She seems to have kept them all, and some are excerpted in the documentary.

Touchingly, Blume developed decades-long relationships with her young correspondents, two of whom the documentary tracked down. One, Karen Chilstrom, says Blume saved her life. She wrote to Blume in 1982, when she was 12, to talk about the suicide of her 17-year-old brother. Later, she reveals to Blume that her brother had molested her for seven years.

“I just needed to be able to tell another human being, ‘Look what happened to me,’” Chilstrom says. “Judy was my last chance.”

Blume’s kindness is the emotional high point of the documentary: “Remember, if you do get overwhelmed by your feelings, you can write about them,” she wrote to Chilstrom. “Whether it’s in letters to me, or your journal or whatever. Keep getting those feelings out.”

Blume has helped generations of kids get “those feelings” out. The repressed adults (still) trying to ban her novels should instead sit down, shut up and actually read the books.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.