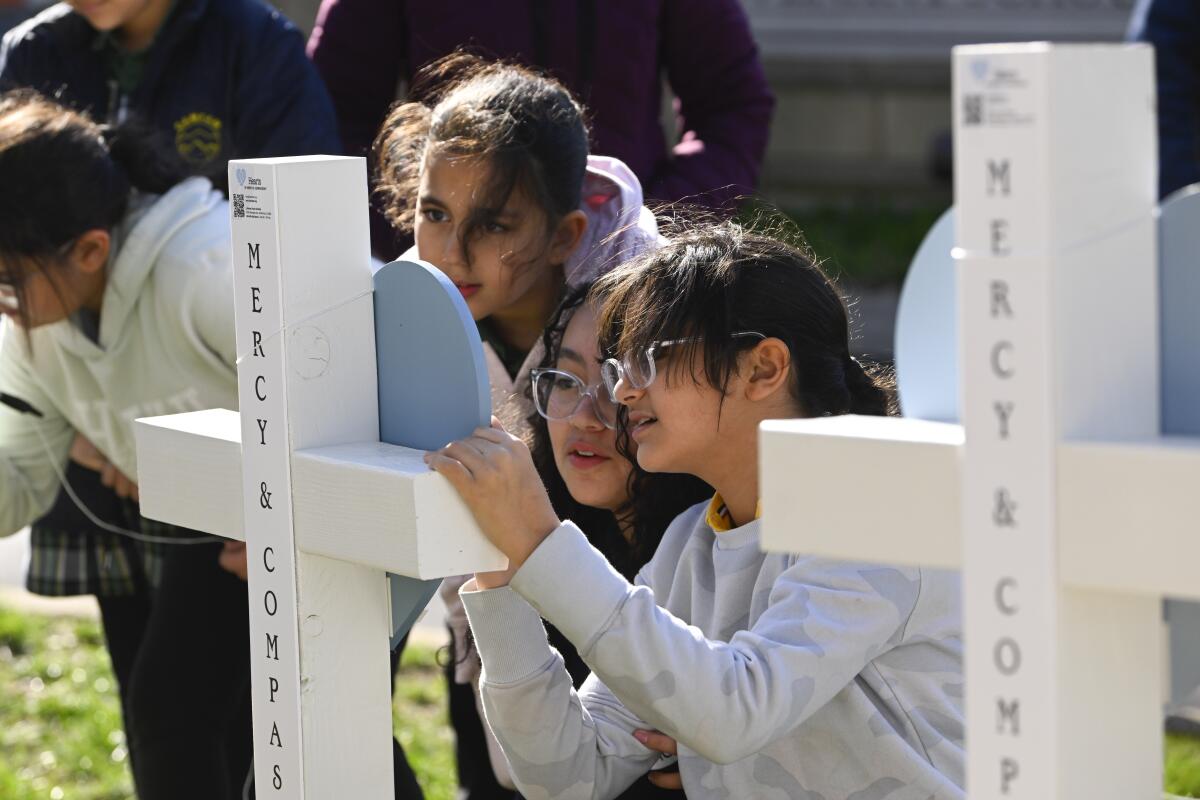

The Nashville shooting was horrific. The gun toll on our children is so much worse

- Share via

Three children and three adults were killed this week in Nashville, the latest city to become the scene of one of our all too regular mass shootings. As a parent, I am horrified to see another school taped off as a crime scene. As a physician who has studied the life expectancy of American children, I know shootings like the one in Tennessee represent only a small fraction of pediatric firearm deaths.

In 2021, the most recent year with reliable data, firearms killed 4,733 American children and youths ages 1 to 19, only 12 of whom — one in nearly 400 — died in school shootings. This awful toll grows every day as young people are shot, one by one, in communities across the country.

America’s young people are now more likely to die from guns than from anything else. The most life-threatening pediatric conditions — cancer, birth defects and heart disease —together claim fewer lives than guns. Motor vehicles, for decades the leading cause of pediatric deaths, fell to second place in 2020, yielding to guns as the top killer of children.

Over most of the past century, “all-cause mortality” — the probability of dying of anything — decreased dramatically among U.S. children, thanks to advances in prevention and medical care. Antibiotics and vaccines conquered infectious diseases that routinely sent children to their graves. Engineering advances such as seat belts and safer designs slashed car crash death rates. Innovations in chemotherapy helped more children survive leukemia.

Now firearms are putting all that progress in jeopardy. In a recently published study, my colleagues and I found that American children and teens have become significantly less likely to see the age of 20. All-cause mortality among those ages 1 to 19 surged 20% between 2019 and 2021, perhaps the largest such increase since the 1918 influenza pandemic.

America’s assault weapons ban, in effect from 1994 to 2004, shows that such a law enacted now would mean many fewer Nashvilles in the future.

This was not caused by COVID-19 or any other disease. The primary culprits are suicide, homicide, drug overdoses and car accidents, the first three of which began claiming more lives before the pandemic. Pediatric suicides started rising in 2007, homicides in 2013 and fatal overdoses in 2019. We have reached a horrific tipping point at which all the lives saved by pediatric medicine are now being lost to bullets, drugs and car crashes.

This alarming trend underscores two emergencies: a mental health crisis among young Americans and the growing danger of firearms. Politicians seeking to evade discussions of gun policy often pose a false dichotomy: The problem, they say, is not the weapons but the mental health of those pulling the trigger. This is disingenuous not only because both can be a factor but also because the same politicians often oppose meaningful investments in mental health.

The increase in pediatric suicides is one sign that a much larger population of young people is struggling with depression, anxiety and hopelessness. Psychosocial stresses can express themselves in conflict and violence. And impulsive anger or desperation can quickly turn fatal when a firearm is within reach.

In 2021, firearms were involved in 86% of homicides and 48% of suicides among those ages 1 to 19, and the rates are increasing. Guns have replaced overdoses as the leading means of suicide. Firearm-related deaths among young people surged 67% between 2015 and 2019. In 2018, emergency rooms treated more than 11,000 children under 19 for nonfatal firearm injuries. And as of 2021, accidental shootings were killing an American child every other day.

To grow up counting victims of gun violence is not “freedom.” When will we decide that this isn’t how we want to live?

The reasons for the gun epidemic are no mystery to observers in other wealthy countries, where gun violence is rare. Firearms outnumber people in the United States, where gun ownership rates are far higher than in other countries and climbing rapidly. Gun manufacturers have spent years promoting lethal semiautomatic rifles, the weapon of choice in mass shootings. Ownership of assault weapons such as the AR-15 grew from 74,000 in 1990 to 2.8 million in 2010.

The firearms industry and its lobbying arm, the National Rifle Assn., have promoted gun sales by convincing millions of Americans of the need to defend themselves with military-grade weaponry. Some members of Congress now wear assault rifle lapel pins and pose with firearms for their family holiday photos. This macabre climate helps explain why the most modest measures to curb pediatric gun deaths — those that would keep firearms away from children, require storing weapons unloaded, and mandate locks and other safeguards to prevent use — routinely go down in defeat in Congress and state legislatures.

Adults on any side of the gun debate should be able to agree on the wisdom of protecting children from guns. Adults can responsibly use firearms while also supporting policies to prevent children from being shot.

The recent surge in pediatric mortality is a flashing warning light. The fact that young Americans are now most likely to die by a bullet and less likely to reach adulthood should bring us to our senses. Our failure to protect the lives of our children is unconscionable.

Steven Woolf is a professor of family medicine and population health at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.