- Share via

I was 9 years old when my great-aunt, Greta Mae, or Ma Mae as we called her, died of lung cancer. I was too young to visit her in the hospital, but my mom would come home with updates that went from “she’s not doing good” to “it’s going to be any time now.”

On what she knew would be her last visit, my mom came home to tell me that night would be Ma Mae’s last. She told me how Ma Mae was surprisingly in better spirits that evening, after having seen her mother, who came to tell Ma Mae that a room was being prepared for her and as soon as it was ready, Ma Mae’s mother would come back for her.

Ma Mae’s mother, my great-grandmother Alies, had died years before, and I didn’t need my mother to tell me that the visit meant death was looming. Somehow, I understood and I hugged my mother and cried, knowing I’d never see Ma Mae again. I don’t know how I understood but I accepted that sometimes our ancestors and predecessors come back for us in the end to soften the journey.

I was filled with guilt and resentment for what I had to take on. But over time, a community of caregivers helped me find fulfillment.

Three years later, my cousin Maine came home to die. It was 1994 and he had AIDS. My grandmother Irene’s home was the only rest haven open to him. My mom, who’d already taken care of one cousin who died in hospice from AIDS complications, knew there was no risk of contracting the disease from Maine, and knew how important it was for me to be at my grandmother’s house to be there with Maine in his final days.

My grandmother and I hugged Maine, laughed with him, listened to his stories of life away from Charlottesville, Va., and answered his questions about the family members he knew he wouldn’t have the opportunity to talk to face to face. I don’t remember how long he was around or when he died, but I was glad to be there for the many moments of joy.

Twelve-year-old me didn’t know how necessary it was to hold space for the dying, and I had no language for what it was I was doing. At 13, I became a hospice volunteer, sitting quietly, talking, feeding and playing games with patients, but it would be years later before I was able to put a name to the work I was doing to comfort the dying.

I am a Black man and a death doula, a community death-care advocate, who comes from a long line of folks who have done this work without titles for generations. I work closely with many whose skin looks like mine, whose norms, languages and beliefs look very similar to mine, and whose fight against systems of oppression, even in dying and death, look as familiar to me as family. It’s here and it’s in this work that I am able to assist in repairing the community care aspect for the dying and the dead, and to make death a celebration of life.

‘So lonely you could die’ isn’t just a song lyric. Neurogenomics is proving that the human nervous system is not well suited to isolation.

Black grief is different. It’s amplified by constant loss and inequalities. While Black death is traditionally celebrated, when it comes to Black dying, we do little work to prepare ourselves and those we leave behind for the inevitable. A large part of my mission as a Black death doula is to ensure those in my care don’t walk blindly into grief, tragedy or into their final moments alone.

In 2009, my brother’s girlfriend died, and I was immediately at his door. We didn’t speak much, but I sat there for as long as he needed. Four months after my grandfather’s death in 2017, I was talking to a friend about the many experiences I’ve had. My wise friend said to me, “Oh, you’re a death doula.” I’d never heard those two words together, though I knew what a birth doula was. Without letting a second pass, I responded, “That’s exactly what I’ve been doing.” The language was there and it fit in my mouth easily.

Being a Black death doula means I hold space to support the dying and their loved ones emotionally, physically and spiritually in the end. I’ve worn the title for nearly six years. My commitment to this service has led me to seek professional certifications, but certification isn’t necessary to do the work. After all, many of us have supported someone we love as they died.

I couldn’t slow cancer’s march through my Dad’s body. But I could surrender to the gifts of seclusion and quarantine time. Our last time together.

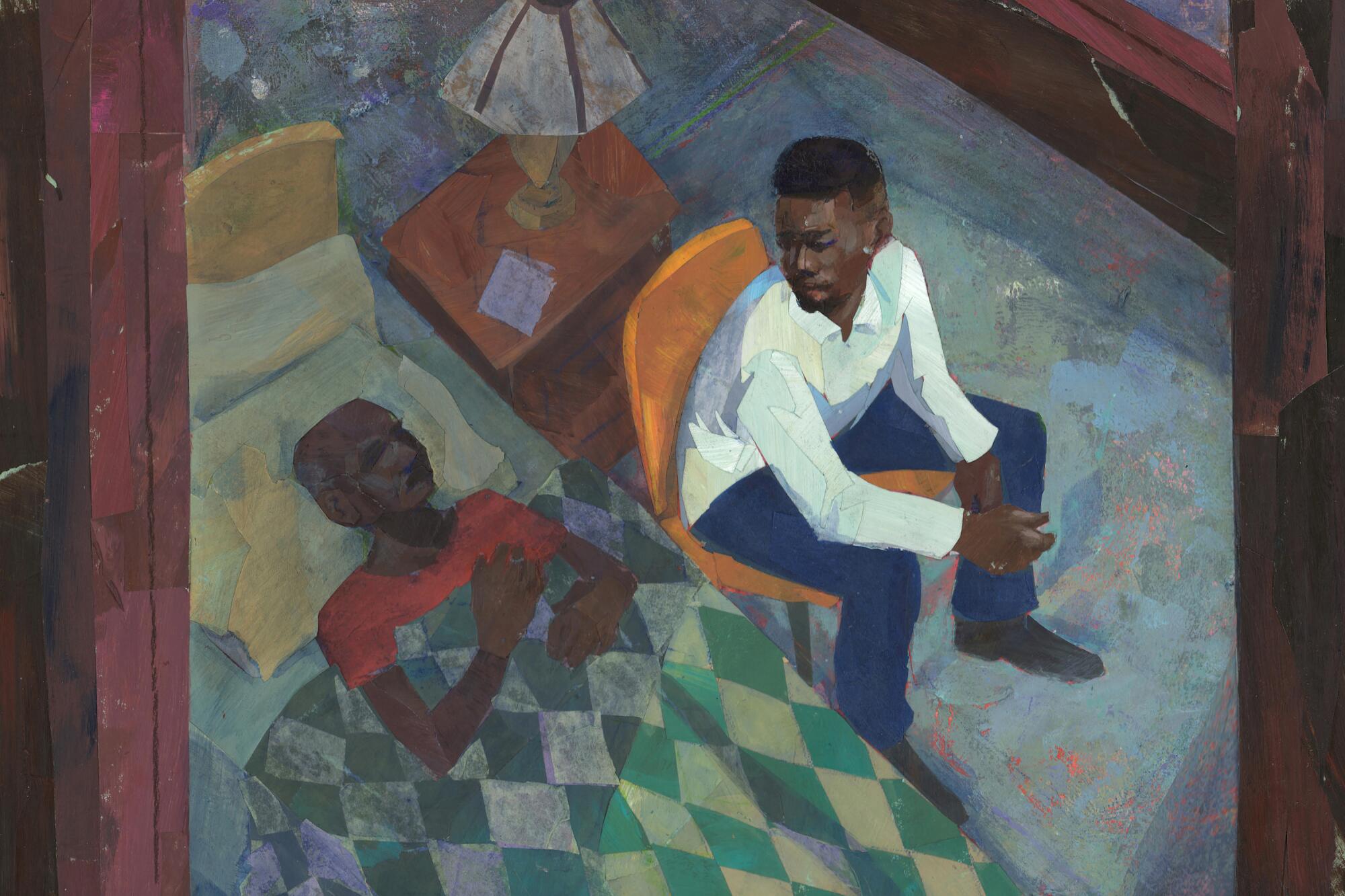

My grandmother Irene, my dad’s mother, died in 2011, and I knew death was coming when she talked about her mother coming to visit her just as her sister had 20 years earlier. Her mother, my great-grandmother Alies, told her, “It’ll be a little while because they’re still getting your room ready.” I flew home as soon as I could and sat in that same ugly hospice chair every day, not waiting for a miracle for my grandmother, but waiting for her to be liberated.

She stopped eating. She was no longer talking, and I knew she was ready; we had talked about how she wanted the end to be many times since I was a kid. It was just her and me in the room when I told her, “Listen, if you are ready to go, go. Everyone is going to be okay because you did great work.” I played Coldplay’s “Fix You,” kissed her on her cheek, squeezed her hand and left.

It took me 20 minutes to drive to my dad and stepmom’s place. I walked in, sat on the couch and the phone rang. I knew what the call was. I suppose I am like my great-grandmother Alies, softening the journey in the end.

Darnell Lamont Walker is a filmmaker and an Emmy-nominated children’s television writer whose work includes “Blue’s Clues,” “Karma’s World” and “Work It Wombats.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.