Editorial: Are California school kids drinking water tainted with lead? We don’t know, and that’s the problem

- Share via

Children attending older California schools are in danger of exposure to lead-tainted water because drinking fountains and faucets have not been tested for unsafe levels of the toxic metal. Lead exposure is particularly dangerous for young kids, whose bodies are developing.

Assemblymember Chris Holden (D-Pasadena) is trying to fix that with a bill that would require the water fountains and faucets at public and private schools built before 2010 be tested every five years and cleaned up if tainted with lead. The legislation, sponsored by the nonprofit groups Environmental Working Group and Children Now, is a sensible solution to a problem that has been vexing environmental health advocates for years.

For the record:

1:27 p.m. Feb. 10, 2023An earlier version omitted Children Now as a sponsor of the bill.

California has enacted several laws since the 1970s to limit lead exposure from products such as paint, pipes and plumbing materials. Drinking fountains in older schools are of particular concern because children, whose bodies can absorb more lead than adults, are most susceptible to the health hazards of the metal.

Resisting gun control is one of the many ways our country’s leaders tolerate violence against children whom they have the power and responsibility to protect.

Though a 2017 law required schools built before 2010 to test their water sources for lead, it didn’t require schools to test all faucets and required remediation only if the water contained more than the federal standard of 15 parts per billion, which health experts have long disputed as unsafe. Even commercially bottled water has a maximum allowable lead level of 5 ppb. The results revealed that nearly 1 in 5 of the 8,200 schools required to test have a drinking fountain with water containing more than 5 ppb of lead.

There are no safe levels of lead in drinking water because even low levels can be dangerous, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, American Academy of Pediatrics and World Health Organization. Lead exposure can cause learning difficulties such as attention deficit disorder and hyperactivity, in addition to high blood pressure, reproductive problems and organ damage. Damage from lead poisoning is irreversible.

Holden’s bill would close the gaps in the 2017 law by requiring the schools to test all drinking and cooking faucets and remediate those with levels above 5 ppb. Under the bill, the testing has to be conducted by local water utility companies because they have the equipment and expertise to detect pollutants.

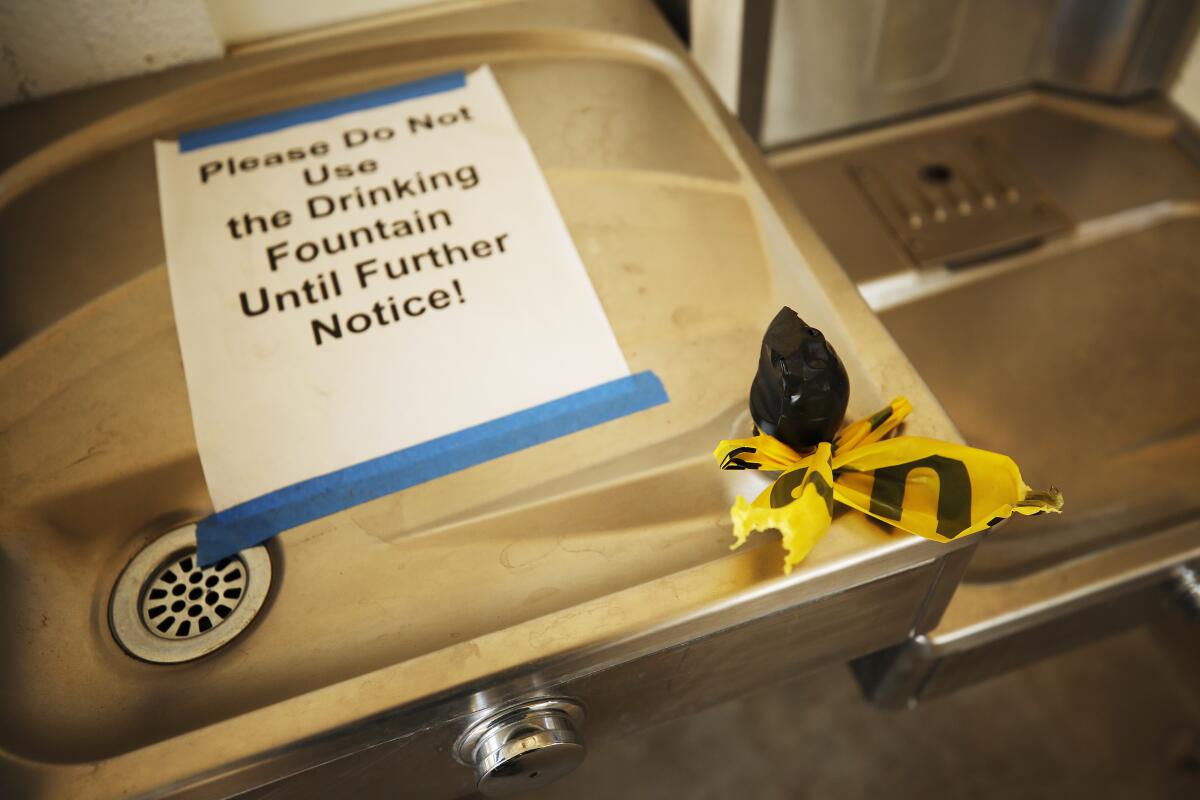

If lead is found, the school districts would have to shut off any faucets dispensing tainted water and fix the problem. California law requires that students have access to safe drinking water at school. The state will help pay for the first round of testing and repairs with $15 million in grants.

Children shouldn’t be forced to learn and play in hot, asphalt-covered, fenced-in campuses, especially in neighborhoods that already lack park space.

This is also an environmental justice issue. Communities of color and people with low income are most likely to be exposed to unsafe levels of lead because they tend to live in older homes, which may still contain lead paint or have lead pipes.

The new bill would also require that parents be notified if lead levels are unsafe. Legislators should add language to ensure adequate notification. At the moment, the bill leaves it to school districts to define. Posting a note on a school’s website, for example, would not be sufficient to get the message to communities that lack digital access.

Kudos to school districts in San Diego, Oakland and Berkeley that have taken an aggressive approach to protecting children from lead exposure through regular testing and installing permanent water filters at drinking fountains and sinks. But providing safe water for kids to drink during the school day shouldn’t be optional.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.