Op-Ed: 50 years post-Roe, who can predict what U.S. abortion access will look like in another 50?

- Share via

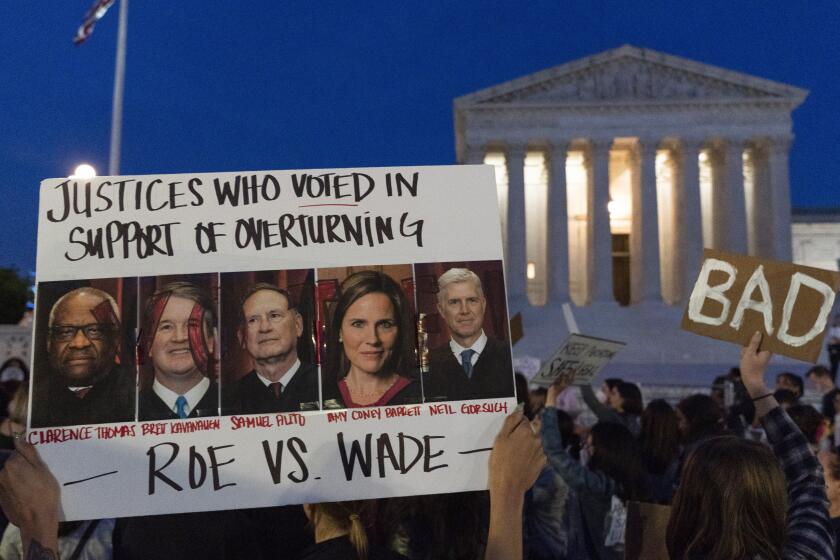

Today is the 50th anniversary of Roe vs. Wade, one quite unlike any that came before it. For one, this year’s annual March for Life protest gathering of the antiabortion movement will end not at the U.S. Supreme Court but somewhere between there and Congress. That’s by design: The Supreme Court last summer already eliminated the abortion right recognized in Roe; elected officials and judges will shape the rules going forward. Without question, a new chapter in the American abortion conflict has begun.

Since the Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling that struck down Roe, it’s been an era of uncertainty and confusion. There are already abortion bans enforced in 13 states, but most conservative legislatures have not been in session since the Supreme Court decision in June. Already, lawmakers in states like Texas and Missouri have proposed measures designed to make it harder to travel for abortion or to get abortion pills in the mail — some of them targeting people in progressive states whose actions are protected where they live. Others are aiming at corporations that reimburse their employees for abortion-related travel out of state.

It’s not clear whether these bills, if they pass, would be constitutional — or even which state’s courts will get to decide. What is obvious is that patients are the ones left to make sense of an ever-changing set of rules.

When we should be celebrating a half-century of progress, it is depressing to be grieving instead for rights that have been withdrawn.

In blue states, residents have to compete with out-of-state patients for scarcer and scarcer appointments. In states with laws that severely restrict or ban abortions, patients committed to ending a pregnancy face daunting travel distances or order pills online, all without any guarantee that they will be protected from punishment. The Alabama attorney general’s office recently claimed that women who take abortion pills could be prosecuted under the state’s chemical endangerment law.

With California at the forefront, progressive states have gone on the offensive, proposing shield laws designed to protect those who perform abortions and help others seeking them. But no one knows whether the protections available under these laws will hold up when conservative courts take a look.

Antiabortion groups have plans to circumvent laws such as Proposition 1, the state constitutional amendment that Californians overwhelmingly endorsed in November. Some hope that a Republican will win the race for the White House in 2024 and will then overhaul the federal Food and Drug Administration, making abortion pills harder to get or taking them off the market.

In the meantime, similar arguments are being raised before conservative judges by antiabortion groups. Other legal challenges to abortion pills rely on an obscure 19th century law still on the books, the Comstock Act, which bans mailing abortion pills. Although the courts for decades have interpreted the law narrowly, abortion foes are hoping that conservative federal judges will read it as a functional ban of all abortion pills.

With so much up in the air, what might the next 50 years of the American abortion debate hold? First, some of the most significant battles will unfold in places we’re not used to paying much attention to. That state legislatures will be major players goes without saying. State supreme courts have already started to clarify whether their constitutions protect the right to an abortion.

Even clear-cut wins and losses will be subject to challenge: 38 state courts use elections as part of their process of selecting judges, and well-funded and organized campaigns will shape who sits (or remains) on each state’s highest courts. Ballot initiatives will continue to be a major point of contest, especially after supporters of abortion rights went six for six in 2022 in these battles. Conservative states may respond by making it harder to get a ballot initiative before voters, or by making it harder to vote.

And the fights may expand beyond abortion. Some antiabortion groups are already targeting chemical contraceptives, arguing that they are no different from abortion pills — or that minors should need parental consent before obtaining them. Some conservative states may look at transforming the practice of in vitro fertilization, barring the disposal of unused embryos, for example. The more extreme these proposals become, the more robust a grassroots backlash we’re likely to see — one that may surpass the mobilization that helped lead to the 1973 decision in Roe.

With abortion care virtually inaccessible in 13 states, it’s imperative to remove barriers where it remains legal.

And speaking of Roe: The fight in federal courts over the right to an abortion is far from over, no matter what the current conservative supermajority would have us believe. In the near term, the conservative justices will probably weigh in on conflicts between the Biden administration and conservative states on issues such as access to abortion in cases of a threat to the patient’s life. Later, the court may be tasked with exploring the constitutional limits of state efforts to limit travel or punish out-of-state conduct. Further along, antiabortion leaders are hoping the Supreme Court will recognize the personhood of the fetus and hold abortion to be unconstitutional across the country.

There may be no chance of reviving a federal right to abortion in the next few years, but there is no reason that supporters of abortion rights can’t replicate the persistence the antiabortion movement showed in the aftermath of Roe. Efforts are already underway to rethink the right to choose abortion: as a matter of equality for women and others who can get pregnant, as a matter of tradition in a nation that committed to ending slavery and the compulsory childbearing of women of color, and as part of an agenda that includes not just being able to avoid pregnancy and parenthood but also the ability to seek out either safely and with dignity. If enough ballot initiatives succeed, it’s even possible to imagine a less-polarized conversation — one in which voters’ views on abortion rights can be separated from their partisan preferences.

Few could have predicted what the following 50 years would look like in January 1973 when Roe came down. The same is true today. But there is one thing we can be sure of: The fight for reproductive rights and justice is not about to end.

Mary Ziegler is the Martin Luther King Jr. professor at UC Davis School of Law and author of “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.