Op-Ed: Why ‘canceling’ the Russian language isn’t the way to support Ukraine

- Share via

During my sophomore year of college in 2010, I picked my major: Russian. I had been studying the language and was excited for the opportunity to read literature, learn about another part of the world and become bilingual. I updated my student profile on the university’s website and marched triumphantly to the cafeteria for lunch.

There, I ran into an acquaintance and told him my decision. He looked at me quizzically, then scornfully said, “You realize it’s not the Cold War anymore, right?”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is now almost a year old, and with divisions over democracy, authoritarianism and control of resources resurfacing, many have warned of a “new” Cold War. But despite Russia once again dominating headlines as a geopolitical foe of the United States, Russian language enrollments have hit historic lows.

By not studying the Russian language, Americans are responding to conflict by closing ourselves off from an adversary, rather than trying to learn about it. But learning to speak Russian isn’t just about negotiating with one large country ruled by a dictator. It’s about understanding the swath of the world where Russian is a common first or second language. Getting to know the diverse life experiences, desires and philosophies of people who once lived under that socialist empire allows us to better understand their cultures and also helps us learn more about ourselves.

Russian-speaking immigrants to the U.S. are facing backlash, but that does nothing to help those suffering in Ukraine.

Foreign language study in the U.S. as we know it grew out of the Cold War. After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in 1957, leaders in Washington worried that we lagged in scientific advancement and lacked expertise about the rest of the world. To help close the knowledge gap, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act in 1958.

Language study got a further boost after a 1979 presidential commission reported that foreign language education in U.S. schools was falling behind once again. In 1976, only about 17% of seventh-graders through 12th-graders were studying a foreign language, and Russian had suffered the most precipitous decline, dropping by 33% from 1968.

In response, in 1983, Congress created another set of appropriations, known as Title VIII, to fund language training and research specifically related to what is now the former Soviet Union.

Data from the annual Survey of Enrollments in Russian Language Classes show that enrollments in Russian-language classes have fluctuated along with university enrollments, peaking in 2011 and declining during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But in 2022, things took a turn. Russian-language enrollment numbers had never been so low. The average university Russian program counted 37 students. (In 2013, when I graduated, that number was 50.)

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine appears to be the key factor in this decline. “Many students have reportedly sought to distance themselves from anything Russia related,” wrote the authors of the survey’s 2022 report.

The problem is symptomatic of an increasing narrowness in the U.S.’ approach to the world, visible in declining support for the humanities, social sciences and education at large, and in blinkered “America First” politics. While the most immediate consequences of this solipsism will likely be seen in diplomatic efforts between Washington and Moscow, its repercussions will extend beyond politics.

My experience speaks to this. Since graduating from college, I’ve almost exclusively used my Russian to communicate with people educated under the Soviet Union who are not ethnically Russian. In 2014, I spent a year in Kyrgyzstan and honed my skills drinking tea late into the night with my roommate. When I moved to Mexico in 2019, one of the first people I befriended was from Belarus; we, too, communicated in Russian. Later that year, a friend who works as an attorney called on me to translate for pro bono clients of hers — Kyrgyz, Uzbek and Tajik families seeking asylum in Mexico.

Putin seeks to erase Ukrainian identity. Replacing the Russian language with their own, Ukrainians are fighting back.

Today, I maintain my Russian in weekly Skype sessions with a tutor in Kyiv. When Vladimir Putin first invaded Ukraine, we “canceled” Russian in our own private way, switching to a beginner Ukrainian textbook. I welcomed the opportunity to diversify my knowledge of Slavic languages.

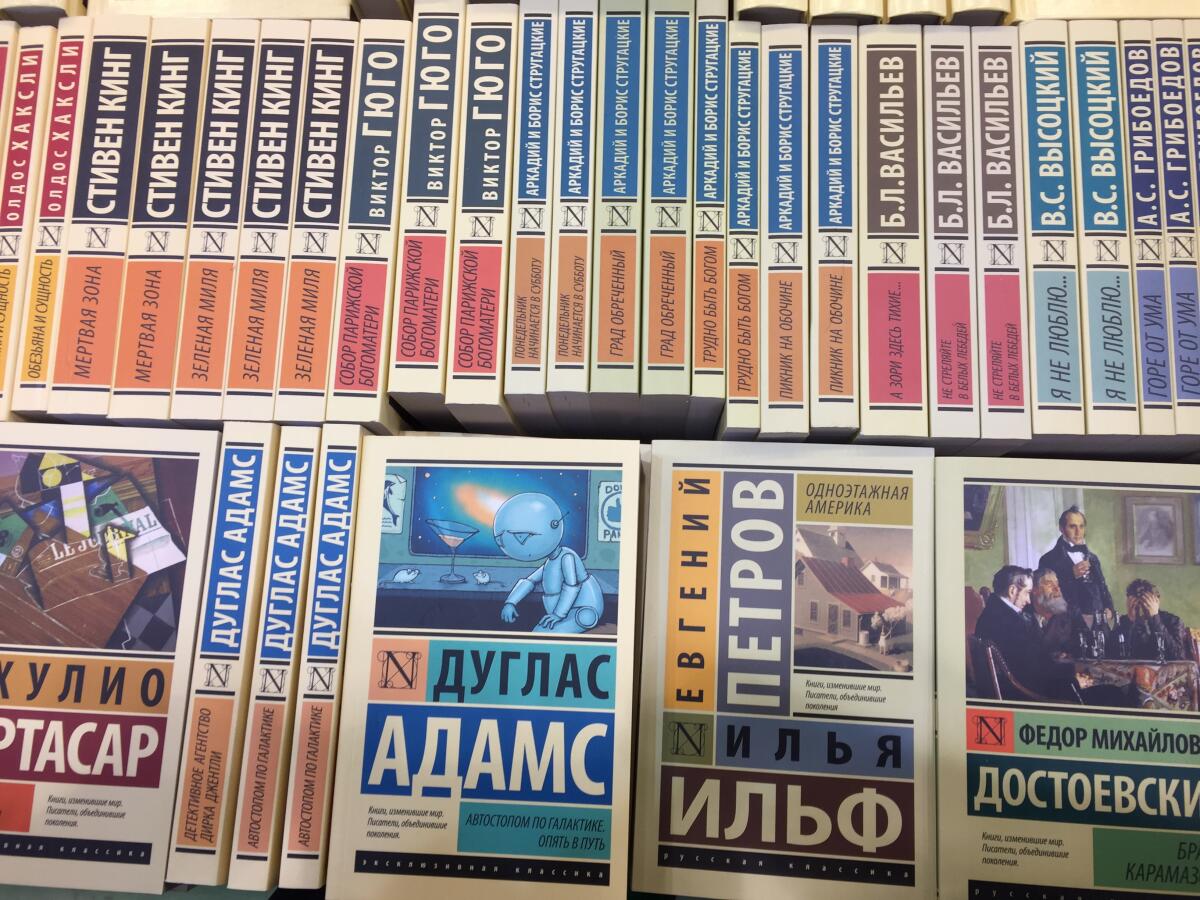

But it was draining repeating basic dialogues without having the time to commit to thorough study of a new language. We missed being able to chat with one another and discuss literature. We switched back to Russian, but with a commitment to read books that were geographically marginal, feminist and antiwar.

In my solitary time, it’s writers at the geographic and political fringes of the former Soviet Union who keep me attached to Russian. Though my college classes favored Pushkin, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, the writers that I pore over slowly in bed in the morning are those who capture life in the provinces and women.

Some, like Svetlana Alexievich and Oksana Vasyakina, occupy the center of this Venn diagram. I value how they speak to the way humans nourish their spiritual and interpersonal needs under repressive political regimes — something I find myself considering more frequently as the U.S. increasingly undermines the democratic processes it once invested so much in creating.

In “Voices From Chernobyl,” Alexievich’s novel about the aftermath of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, one character narrates (in Keith Gessen’s translation):

“There were teachers and engineers among us, and then the full international brigade: Russians, Belarussians, Kazakhs, Ukrainians ... I remember discussions about the fate of Russian culture, its pull toward the tragic ... only on the basis of Russian culture could you begin to make sense of the catastrophe. Only Russian culture was prepared for it.”

When Alexievich’s narrator refers to Russian culture, he’s referring to something far more expansive than Putin and his supporters. Those who are making sense of the catastrophe are working people from all corners of a crumbling empire, using a shared tongue to philosophize together. Those perspectives enrich the world and help us understand it. We lose access to them when we can’t understand their language.

Caroline Tracey is an editor-at-large at Zócalo Public Square and a writer whose work focuses on the U.S. Southwest and Mexico. This article was produced in cooperation with Zócalo Public Square.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.