Editorial: Why L.A. needs independent redistricting

- Share via

In the wake of recent scandals that have rocked Los Angeles City Hall, the simplest, least controversial reform should be the creation of an independent redistricting commission.

It was a good idea before a leaked audio recording caught council members scheming to draw council district lines to help themselves and hurt their foes. But now it’s an essential change to help restore faith in city government.

Politicians should not draw their own districts or choose their voters; it’s a conflict of interest that puts incumbents and their allies’ desires above what’s good for communities. We know there is a better way to draw political boundaries. Jurisdictions that have enacted truly independent redistricting commissions have high levels of public participation, less gerrymandering and districts that represent communities, not individual politicians’ interests.

Los Angeles City Hall has been rocked by scandal after scandal, but now there’s momentum to reform city government.

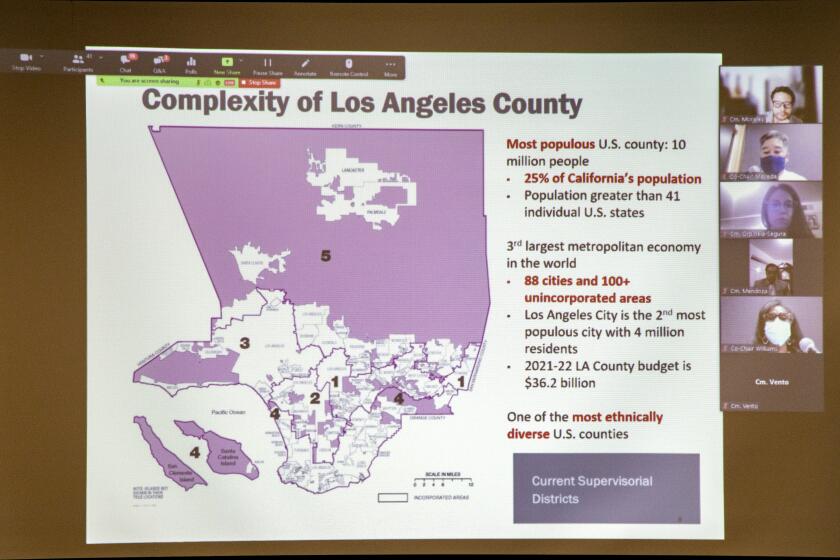

Political districts are redrawn every 10 years to reflect the federal census’ updated population and demographic data. The goal is to make elected bodies more representative of their constituents. Redistricting does this by grouping communities of interest, including racial, ethnic, political and geographical, so they have more influence at the polls and on their elected leaders. When communities are split, their political power to elect a representative of choice is diminished.

The state of California, Los Angeles County, Long Beach, San Diego and several other cities and counties have independent and bipartisan citizen commissions draw the boundaries for congressional, legislative and local government seats and school board districts.

Commissioners are ordinary citizens, not elected officials or political operatives who have a personal interest in the outcome. And the independent commissions do their work in public, so voters know how and why the district boundaries were drawn. People may not like the new lines — redistricting is a balancing of interests — but at least they can trust that the maps were not the product of behind-the-scenes self-dealing.

That’s one reason why California was the rare state that didn’t have a lawsuit challenging its 2021 redistricting. The great majority of states allow the politicians who control the Legislature to draw districts that benefit their party. As a result of two ballot measures in 2008 and 2010, California voters created an independent citizens commission made up of Republicans, Democrats and independents to draw political boundaries for state legislative and congressional districts.

We asked Los Angeles’ elected leaders and candidates if they would support asking voters to approve an independent redistricting commission.

The state commission held months of hearings, took more than 36,000 public comments and — after some chaotic meetings and tense sessions of map drafting — unanimously approved the final maps in December. The new district boundaries have led to competitive races and more representative districts, including an increase in the number of legislative and congressional districts with a majority Latino citizen voting-age population, which is more reflective of the state’s population, and that’s good for democracy.

In Long Beach, the independent commission, which was new in 2021, finally got rid of the “whale tail,” the nickname for a City Council district that had been ridiculously elongated 20 years ago so a council member could locate his field office in a particular park far away from the bulk of his district, according to the Long Beach Post. Yes, the district did look like a whale and its tail.

After decades of having the city’s Cambodia Town split among four council districts — thus making it harder for the Cambodian community to elect a representative of its choice — the commission united the neighborhood into one district. (Long Beach is home to more Cambodian Americans than any other city in America.) The commission’s final maps drew two incumbents out of their districts.

Across the state, race, ethnicity and representation were actively debated during redistricting. Most independent commissions aim to keep communities of interest together so they have a better chance of electing a representative of their choice. But, again, the discussions, decisions and balancing are done with full disclosure.

Unlike other states facing lawsuits for drawing unfair political maps, California has satisfied many constituencies in our diverse state.

Compare that with what we heard on the leaked audio of then-council President Nury Martinez (she has since resigned) and Councilmembers Kevin de León and Gil Cedillo. They were meeting with Los Angeles County Federation of Labor President Ron Herrera to discuss maps proposed by the city’s advisory redistricting commission and, specifically, Latino underrepresentation on the City Council. Latino residents make up roughly half of L.A.’s population, but less than a third of the council’s 15 council members are Latino.

But as the racist and demeaning comments and the machinations on the recording revealed, they were really just plotting how to manipulate the maps to retain their power and diminish that of their perceived enemies. And that’s allowed under the city’s current redistricting system.

Though it purports to be an independent citizens panel, L.A.’s commission is not. The most recent group of 21 commissioners — appointed by city politicians and serving at their pleasure — included former elected officials and longtime political aides. The last two redistricting commissions in 2011 and 2021 have been rife with meddling and string-pulling by elected officials.

In 2021, elected officials were allowed to have back-channel conversations with commissioners during the process, and they replaced their appointees when they weren’t happy with the line-drawing.

City Council members have the final vote and can adjust the proposed lines to their own advantage, as Martinez did last year when the council redrew San Fernando Valley maps to keep two economic assets — Sepulveda Basin and Van Nuys Airport — in her district.

The good news is that there is consensus that L.A.’s corrupt system needs to be replaced. We surveyed current city elected leaders and candidates, and every respondent supported putting a measure on the ballot asking voters to create an independent redistricting commission, similar to what Los Angeles County and the state of California have.

Last month the City Council voted to begin the process of putting an independent redistricting commission on the 2024 ballot or sooner. Separately, City Atty. Mike Feuer wants to call a special election in the spring to fast-track an independent redistricting commission and redraw the council district lines before the 2024 election. Councilmember Monica Rodriguez has pushed for state legislation that would force the city to do the same.

Local philanthropic groups are funding an independent review of Los Angeles governance, including independent redistricting, and are expected to press city leaders to put the reforms on the ballot.

California Common Cause, a key advocacy group behind most of the state’s redistricting reforms, has said that if the city fails to act, it will launch a ballot initiative for 2024. The group is also exploring legislation that would that require that cities over a certain size conduct independent redistricting.

Independent redistricting is long overdue in Los Angeles. Now is the time to make it happen.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.