Editorial: Learning loss is bad everywhere, and demands immediate action

- Share via

It’s no surprise that educational achievement suffered after two chaotic years of school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. But it’s still distressing to see the desolate picture of students’ academics and ever-widening gap between low- and high-performing students revealed by the latest national proficiency test scores.

Math and reading scores declined among fourth- and eighth-grade students in most states, according to results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress released Sunday. Overall, the “Nation’s Report Card,” as this periodic report is known, showed such steep declines in test scores compared with previous years that education experts warn that we’re on the verge of losing an entire generation to substantial learning loss.

California students fared slightly better than students in most other states, with small declines in math but less significant changes in reading. However, California students are still underperforming compared with national standards. Most troublingly, low-performing students’ scores declined at much higher rates than higher-performing students. For example, the average score in 2022 for students at Los Angeles Unified schools who are eligible for the free lunch program was 35 points lower than students who didn’t qualify for that program. In 2002, that difference was only 14 points.

The results are hardly surprising given the unprecedented disruption in schooling caused by the pandemic, but they offer concrete proof that K-12 students need more focused attention and resources in the form of tutoring or extended instruction time, depending on specific circumstances. More than just a snapshot in time of how students are faring, the results offer clues for educators, policymakers and parents of how we can better help students. The larger declines in math could mean that students need more support, perhaps one-on-one tutoring or more teacher instruction.

The L.A. Times’ editorial board endorsements for statewide ballot measures, elected offices in Los Angeles city and county, L.A. Unified School District board, L.A. county superior court, statewide offices, the state Legislature and U.S. House and Senate seats.

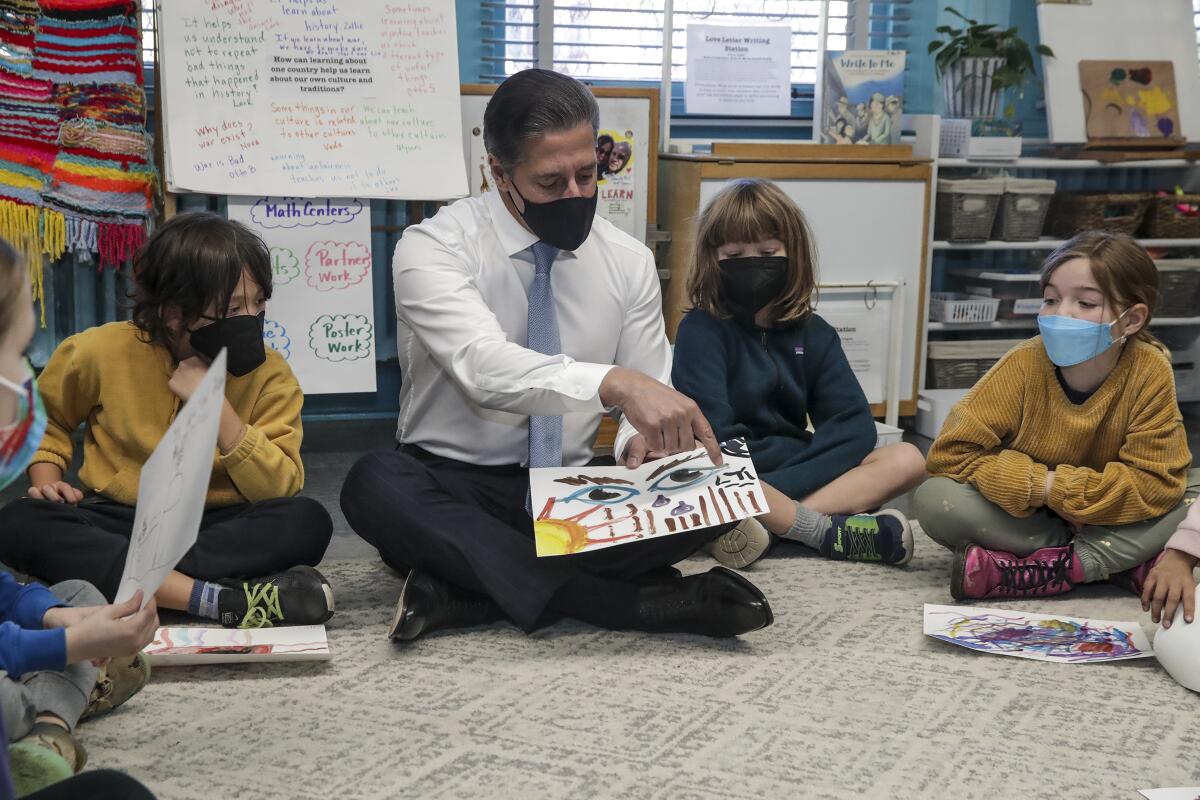

U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said the poor performance isn’t just the result of school closures during the pandemic but also a reflection of “decades of underinvestment in our students.”

Nearly 500,000 fourth- and eighth-grade students nationwide took the tests between January and March. The report card is helpful because it contains data for students in all 50 states and 26 urban districts, including Los Angeles and San Diego, which educators can use to glean information about best practices in areas that showed improvement from 2019, when tests were last administered.

For example, the declines at Los Angeles Unified weren’t as steep from 2019 to 2022 as had been feared, considering the many challenges — including high poverty rates, a dearth of affordable housing and lack of reliable, affordable Wi-Fi — faced by students in the second-largest school district in the country.

Nevertheless, LAUSD eighth-graders improved their reading scores by 9 points from 2019 to 2022, a notable gain in a sea of losses. LAUSD Supt. Alberto Carvalho credited many factors for this progress, including the district’s quick pivot to virtual learning, targeted tutoring of high-need students and mental health support for students.

Some education factions insist that students didn’t suffer academically last year. This rosy view can only evade accountability and hurt kids.

Carvalho called himself a data-driven administrator when he took over leadership of the district earlier this year. This report card, along with the troubling results of the state-mandated standardized California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress released Monday, provide a lot of data that he can use to better direct resources for students, parents, teachers and other staff.

It’s clear that a multi-pronged approach to boosting student performance will be necessary, but state and local educators and policymakers should ensure that decisions about how to allocate resources are driven by data and other evidence.

California schools received $15 billion from the American Rescue Plan. The state created the $4.6-billion Expanded Learning Opportunity Grant in 2021, issuing a set of guidelines for districts to spend on designated support such as additional staff, but it’s up to districts to come up with plans that meet their needs.

The data released this week show the urgency of remediating the learning loss exacerbated by the pandemic. Now that educators have the funds and the data to help guide them, they should use that money wisely. Our children’s future depends on it.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.