Op-Ed: How the pandemic is changing higher education for the better

During college graduation season, itâs easy to get swept up by the notion of the great promise of higher education, even if recent statistics tell a different, more sobering story.

The publicâs view of the value of a college degree has continued to decline, shockingly so. Only about half of 1,060 high school students surveyed in January say they want to earn a four-year degree. And enrollment â already predicted to sag throughout this decade â has fallen scarily in the last two years in almost every postsecondary sector.

For the record:

12:34 p.m. June 13, 2022In an earlier version of this article, Los Angeles City College was referred to as Los Angeles Community College.

Since the pandemic hit more than two years ago, 1.4 million students who were registered for college have dropped out, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Perhaps even more disturbing is the rapidly rising number of Americans who have earned some college credits but no degree. In 2020, that applied to 36 million of us; in two short years that figure has climbed to 39 million.

The largest percentage, more than 16%, live in California. This is not surprising since the state has the largest population of college students in the U.S. â more than 2.6 million potential graduates are enrolled.

California Community College students can decide whether they want a letter grade, a pass/no pass credit â a transcript lifeline of sorts designed to prevent students from dropping out.

The pandemic is commonly blamed for higher educationâs poor showing, a statement thatâs more convenient than fair.

Before COVID showed up, we and others had already identified key issues that would alter the higher-education landscape. Students from underserved groups were being affected by food and housing insecurity, the digital divide, the high cost of textbooks, and the expense and inaccessibility of childcare. COVIDâs contribution â brutal and catastrophic â has accelerated the challenges students face while trying to earn postsecondary degrees or credentials.

The pandemicâs influence on higher education will be long-lasting and transformative â but not necessarily negative. It has created an opening for colleges to reform in a way unseen since post-World War II, when returning solders attended college on the GI Bill; in 1947 they accounted for half of all college students. The number of degrees awarded doubled between 1940 and 1950, partly because schools found a way to award academic credit for learning gained during military service. Many veterans could earn a degree in less than four years.

Today, leaders in higher education are using lessons learned during the pandemic to reshape their institutions in ways that otherwise might have taken years to implement â if they occurred at all, according to interviews we conducted over the last year.

Many of the dozen people we have spoken with so far are presidents of community colleges, which were affected by the pandemic more than most institutions. The changes community colleges make are often harbingers of what postsecondary education for everyone will look like down the road. Their traditional focus on low-tuition, college-to-career training and enrollment of students from underserved groups are construction-ready blueprints for higher educationâs future.

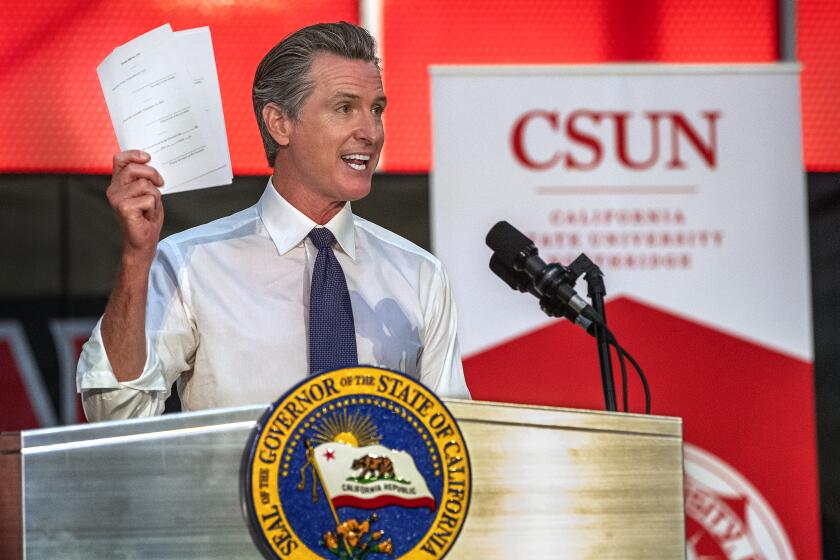

The education package signed by Gov. Newsom includes legislation that will help community college students transfer into four-year universities.

Grand Rapids Community College President Bill Pink â like almost every other college leader â discovered his Michigan institution was utterly transformed by the pandemic. Unlike many other higher-education leaders, Pink, now the incoming president at Ferris State University in Michigan, fully embraced that transformation. He found that offering more flexibility helped students complete their degree requirements.

Before the pandemic, Grand Rapids offered classes that were 80% in-person and 20% online. Those numbers are now flipped, which enables the school to reach more students, especially those who didnât enroll for the simple but overarching reason that courses were offered at times they couldnât get there. After an initial 9% decrease during the pandemic, enrollment at Grand Rapids increased about 1% between 2021 and 2022 â at the same time national public community college enrollment decreased by about 8%.

Los Angeles City College shifted to a full-remote class schedule. Mary Gallagher, the schoolâs president, knew that most students prefer remote classes and 24/7 accessibility. But she also realized that many subjects require in-class engagement. In response, the campus is developing on-demand science labs. Trained staff will be available to assist students as they complete their required labs, regardless of the time of day or night.

Beyond the classroom, higher-education leaders are also reimagining the way they deliver pivotal student services. Pre-pandemic, community colleges especially started emphasizing student support practices that included peer advisors, learning communities, faculty advisors and mental health counselors.

These investments are making a big difference. They have increased graduation rates for the new majority of students, who are often the first in their family to go to college. They tend to be older than 25, so-called Dreamers, and from low-income and historically underrepresented communities. Often, they are already parents.

John Sygielski, president of Pennsylvaniaâs Harrisburg Area Community College, responded by creating a comprehensive student center focused on providing for needs such as food and housing insecurity â and round-the-clock mental health services.

It is no secret that the mental health of college students (as well as faculty and staff) has been significantly strained during the pandemic, with nearly 1 in 5 students grappling with suicidal ideation. Almost every leader we spoke with said this was a primary concern. During the pandemic, the Harrisburg administration learned that students preferred accessing mental health services online. Greater anonymity, along with expanded service hours, made vital mental health interventions much more accessible.

Our new college graduates, pandemic veterans all, should be congratulated for their perseverance and for earning their degrees during a historic public health nightmare. Educators must take the lessons they learned during the pandemic and use them to create a college experience that invites more students in â and gives them the support and flexibility they need to succeed.

Stephen J. Handel is a senior program officer with ECMC Foundation in Los Angeles. Eileen L. Strempel is the inaugural dean of the Herb Alpert School of Music at UCLA. They are the authors of âBeyond Free College: Making Higher Education Work for 21st Century Students.â

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.