Editorial: Fix the biggest flaw with California’s recall or next time a loser could win

- Share via

California’s system for recalling politicians has an enormous flaw: It creates the possibility that an elected official could be thrown out of office and replaced by someone voters like even less.

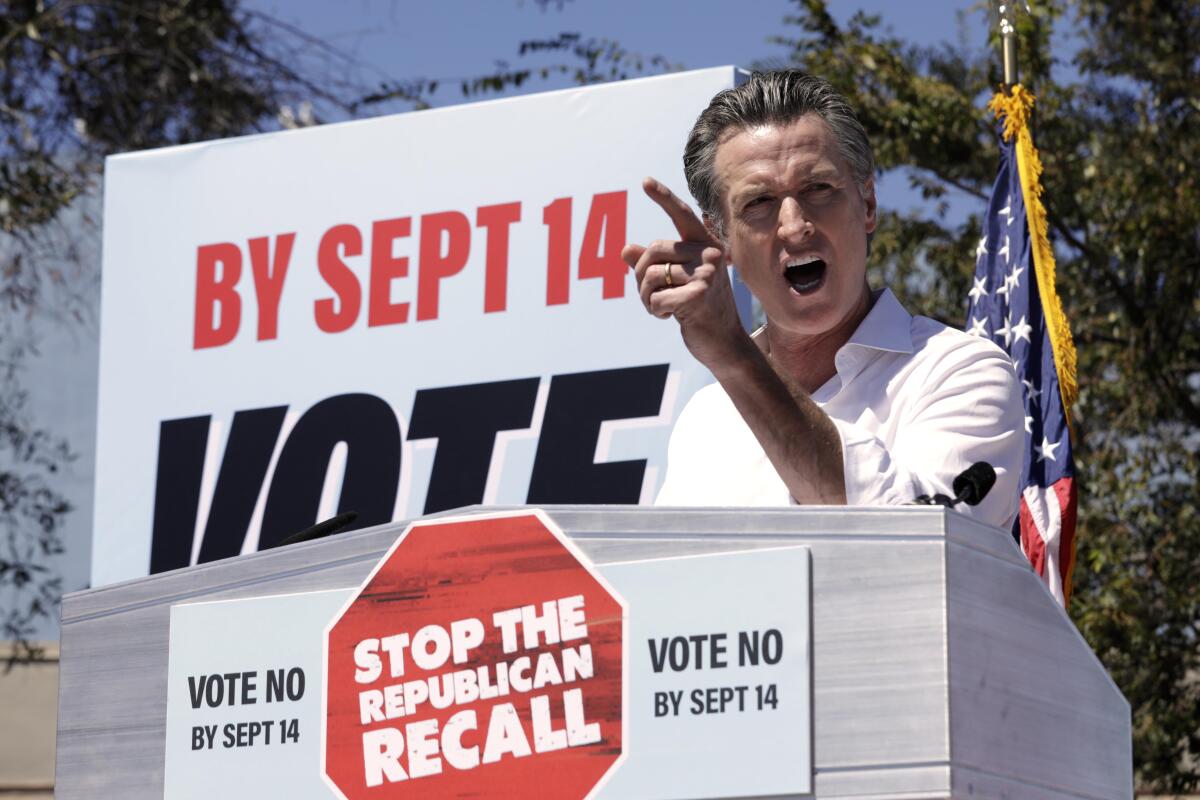

This didn’t happen last year, when 62% of voters said “no” to recalling Gov. Gavin Newsom, keeping him in office and sending the 46 people who ran to replace him back to their talk radio studios, YouTube channels, reality TV shows, pink Corvettes and losing legislative agendas.

But it could have. Because while it takes a majority vote to win the yes/no recall question, it takes only a plurality to win the who-should-be-the-replacement question. If, hypothetically, 49% of voters had said “no” to the recall, Newsom would have been recalled and replaced by whoever received the most votes — even if that person received only, say, 40% of the votes.

That’s what happened in 2018, when Orange County voters threw state Sen. Josh Newman (D-Fullerton) out of office. While 42% voted against the recall, meaning they wanted to keep Newman on the job, he was recalled and replaced by Ling Ling Chang (R-Diamond Bar), who prevailed in a field of six candidates with support from 34% of voters. In raw numbers it worked out like this: 66,197 people voted to keep Newman in office and 50,215 voted to elect Chang. But Chang won and Newman lost.

The 110-year-old recall rules are showing their age and need updating. Most Californians agree.

That violates a foundational principle of our democracy — that the person with the most votes wins. And it flies in the face of California’s top-two system that ensures our state leaders win office with support from a majority of voters. Worst of all, this flaw undermines the power of the recall as a legitimate tool to help voters hold elected officials accountable. Instead, it’s made the recall a potential path to victory for politicians who can’t appeal to enough voters to win a regular race.

Fixing this flaw should be the singular focus of any proposal lawmakers put on the ballot to change the recall system.

Over the last few months, state lawmakers have reviewed proposals to change many aspects of the recall. They’ve identified several questionable features of our 111-year-old procedure. California allows a recall to reach the ballot with a smaller portion of signatures from voters than most states require. A recall here can be launched at any time in an official’s term, which allows voters unhappy with an election’s outcome to begin trying to throw the winner out as soon as inauguration day. Unlike some states that require a standard of malfeasance, California allows voters to start a recall for any reason.

But trying to make too many changes at once would be foolish. It risks coming off like a California version of Texas, or the other red states where Republicans changed a raft of voting laws following an election they didn’t like, when Democrat Joe Biden won the presidency.

“Voters are viewing election reforms through a partisan lens,” said Mark Baldassare, president of the Public Policy Institute of California, which has been polling voters about the recall. “For reforms to get the kind of support they would need in California, they would need to be viewed as in the best interest of democracy.”

Eliminating the chance that someone can win with minority support is unequivocally in the best interest of democracy. Some of the other proposed changes — such as raising the threshold for signatures needed to put a recall on the ballot, or limiting when voters can launch a recall — may be seen as making it harder for Republicans to recall Democrats. Pursuing these would be a mistake.

Legal scholars say courts would uphold California’s recall law, even if an incumbent were replaced by someone with fewer ballots.

The fix is relatively simple, and already in place in most states that allow recalls: Make the recall one yes or no question. If a majority of voters say yes, then the office is filled in the same manner as if the official resigned or died. For governor, that means the lieutenant governor takes over.

A recent poll showed 50% of California voters like this option. It’s also favored by Secretary of State Shirley Weber, who said she came to that conclusion after consulting with a panel of experts led by former Gov. Jerry Brown, a Democrat, and former state Supreme Court Justice Ronald George, a Republican.

Of course, this plan also has its detractors. Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis and several of her predecessors argue it would incentivize lieutenant governors to undermine the governor, especially if the two are of different parties. But a lieutenant governor has little purpose other than to replace the governor if there is a vacancy.

The law should be rewritten so the lieutenant governor only holds the governorship until the next regularly scheduled general election, rather than the rest of the term. That would make the job a caretaker position until voters choose the next governor through primary and general elections, without the expense of adding a special election.

California’s Little Hoover Commission, which studies state governance, favors a different plan that eliminates the yes/no question and puts the official facing recall on the same ballot with the potential replacements. Whoever gets the most votes wins, and the recall fails if the winner is the incumbent. This eliminates the chance of someone winning with less support than the ousted official has. And it is efficient, because the decision is made in a single election. But it does not address the problem that a winner could still prevail with less than a majority of the votes.

Californians will likely reject changes to the recall that take away their power or feel like a partisan power play. Lawmakers must ensure that the recall remains an option in our direct democracy — and that whoever wins does so fair and square.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.