Newsletter

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

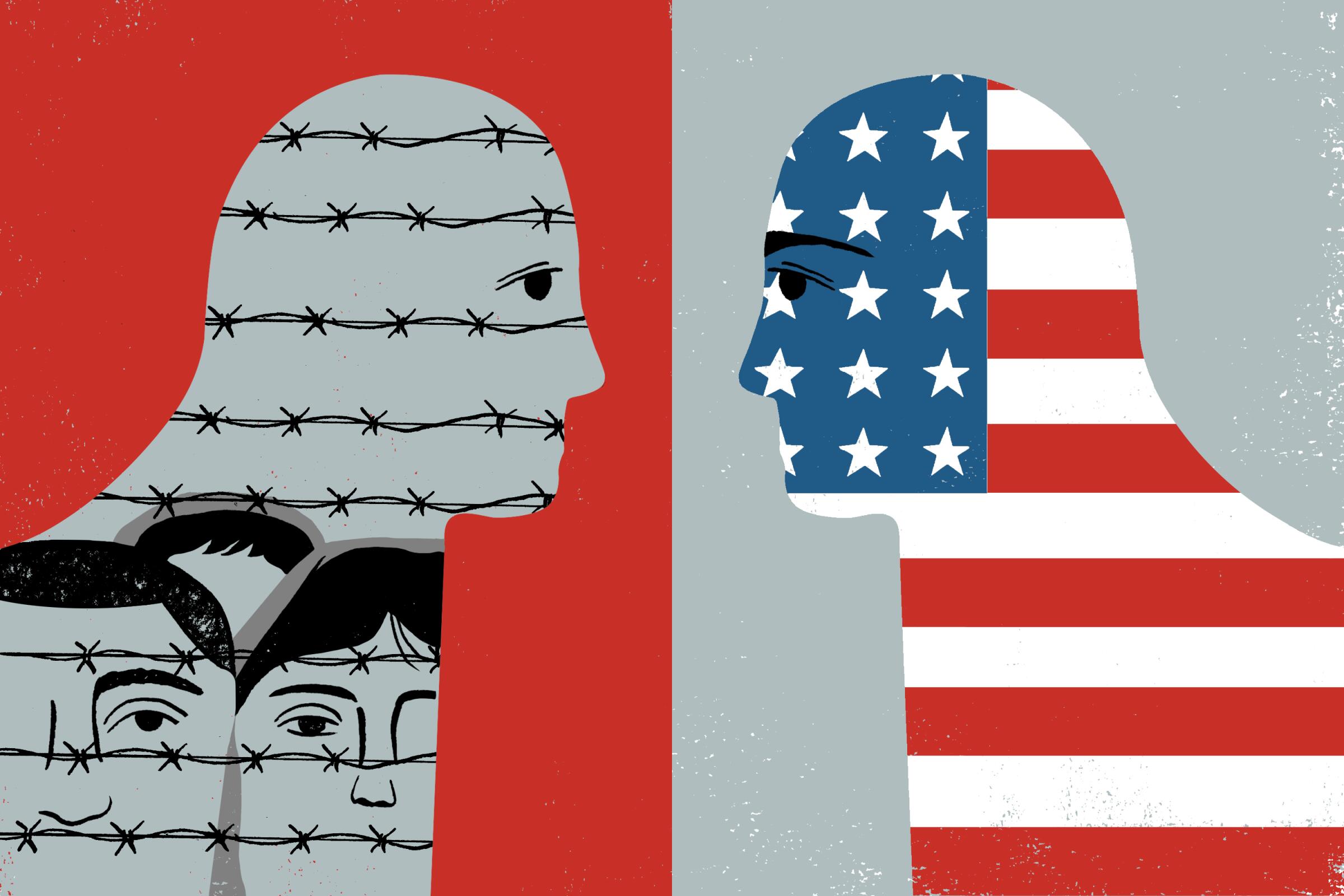

Since Donald Trump was inaugurated in 2017, our letter writers have occasionally compared the current political situation in the U.S. to Germany’s crumbling democracy both before the Nazis were elected into power and before the start of World War II. Since the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, those comparisons have been made more frequently by letter writers.

With the United Nations 2022 Holocaust Remembrance events underway, we asked some readers and letter writers who survived the Holocaust what they thought about those comparisons, and what they want people today to know about that era, less than 80 years ago, when 6 million Jews in Europe were murdered and millions more were enslaved or forced to flee their home countries.

— Paul Thornton, letters editor

When I was a teenager, I asked my father what it was like to live in Germany after Hitler came to power.

“Das kanst du dir nicht vorshtellen” — you cannot imagine it. “At first we thought it wouldn’t be so bad, but some things changed almost overnight. My boss said I shouldn’t visit certain clients because they might not want to do business.”

“But you hadn’t changed!” I interrupted.

“My child, you can’t understand, and God willing, you won’t have to. The boss said he personally didn’t go along with Hitler’s Nazi rantings, but by 1934 we were no longer invited to their Sunday kaffeeklatsch.”

I remembered this when a pro-Trump neighbor stopped inviting us to her annual holiday cocktail party.

Prior to 2016, we respected each other’s differing political views, even joked about it. This changed dramatically after I said to her, “But Trump lies.” That was the end of the conversation, and she and her partner retreated to their capsules of collusion, for it is a form of collusion when normal, ordinary people look away from facts.

It was the same collusion as when teachers, lawyers and ministers went along with the Nazi lie that in a pure Germany, Aryan supremacy must be returned to “das Volk.”

My parents left Germany for France in 1935; I was born there in 1938. Too many of our relatives were less fortunate, and they were gassed in the camps.

For a time I wanted to believe that the Nazi era was a “never-again” episode orchestrated by some twisted fascist monsters. I wanted to believe that America had saved Europe from the worst evil in modern times.

Alas, “never again” is now.

I fear not enough good people remember history. Why are so many Republicans on board with Trump, even a year after the Jan. 6, 2021, coup attempt? I worry about political things, such as the large number of judges Trump has appointed, but there are also other changes that deeply concern me.

I wonder about doctors who refuse to call COVID-19 the killer that it is, especially of poor Americans and people of color. My grandmother was a victim of the Nazification of medicine. She had leukemia. It was treatable with transfusions that she received regularly at a blood bank in Frankfurt. After the Nuremberg Laws, she was denied pure Aryan blood. Her oldest son stayed in Germany to donate blood to her even though he had received an exit visa to America. She feared he wouldn’t get out in time.

My grandmother stopped eating so her son would leave. She died.

Where were the good doctors, journalists or judges who could have demanded this cruelty stop? Where were the ruling bodies then?

And where will ours be in 2022 and 2024 if so many election officials have been ousted or quit because they failed to cheat for a would-be fascist dictator? I pray for our democracy, which seems irrevocably on life support.

— Josie Levy Martin, Santa Barbara

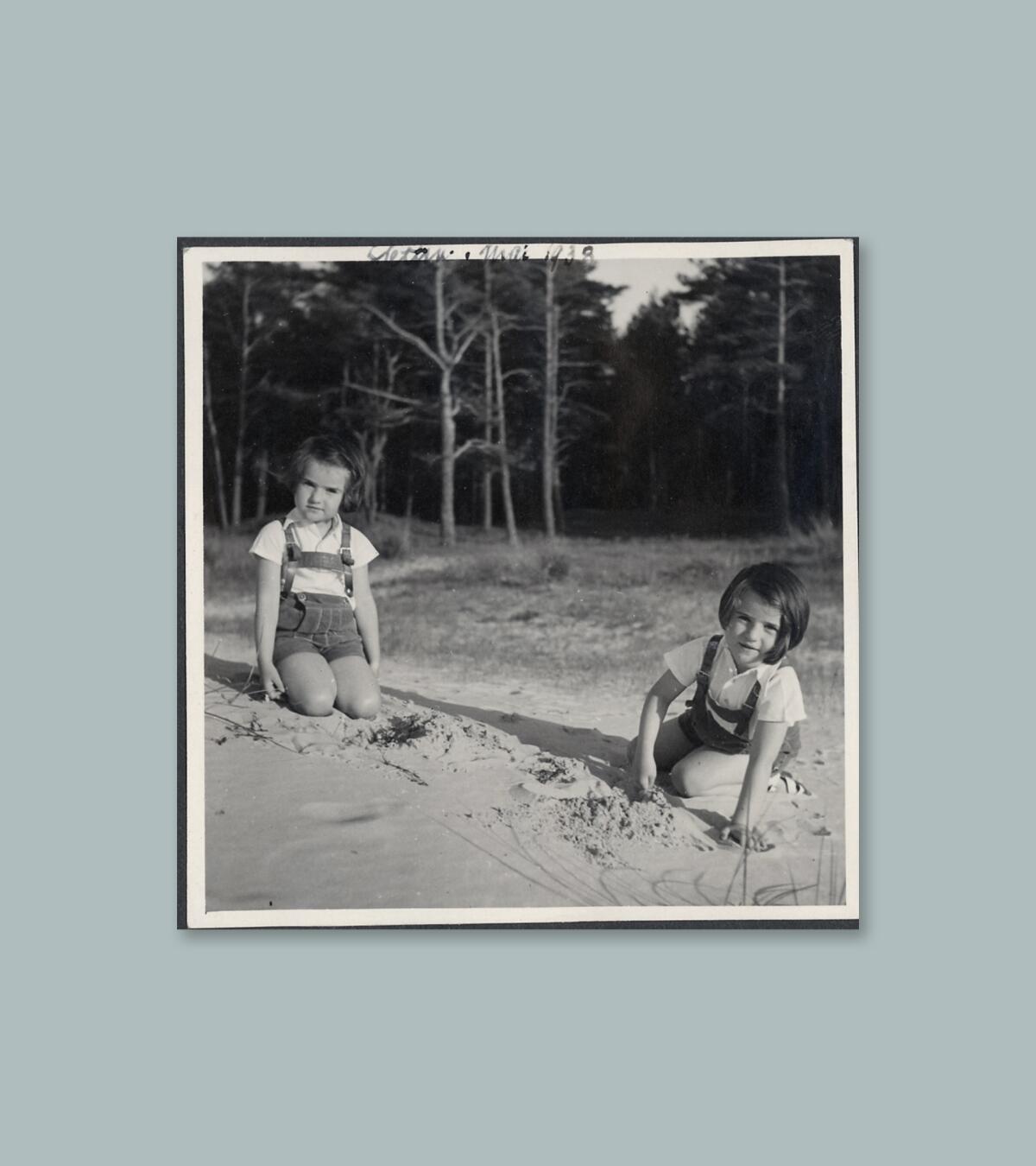

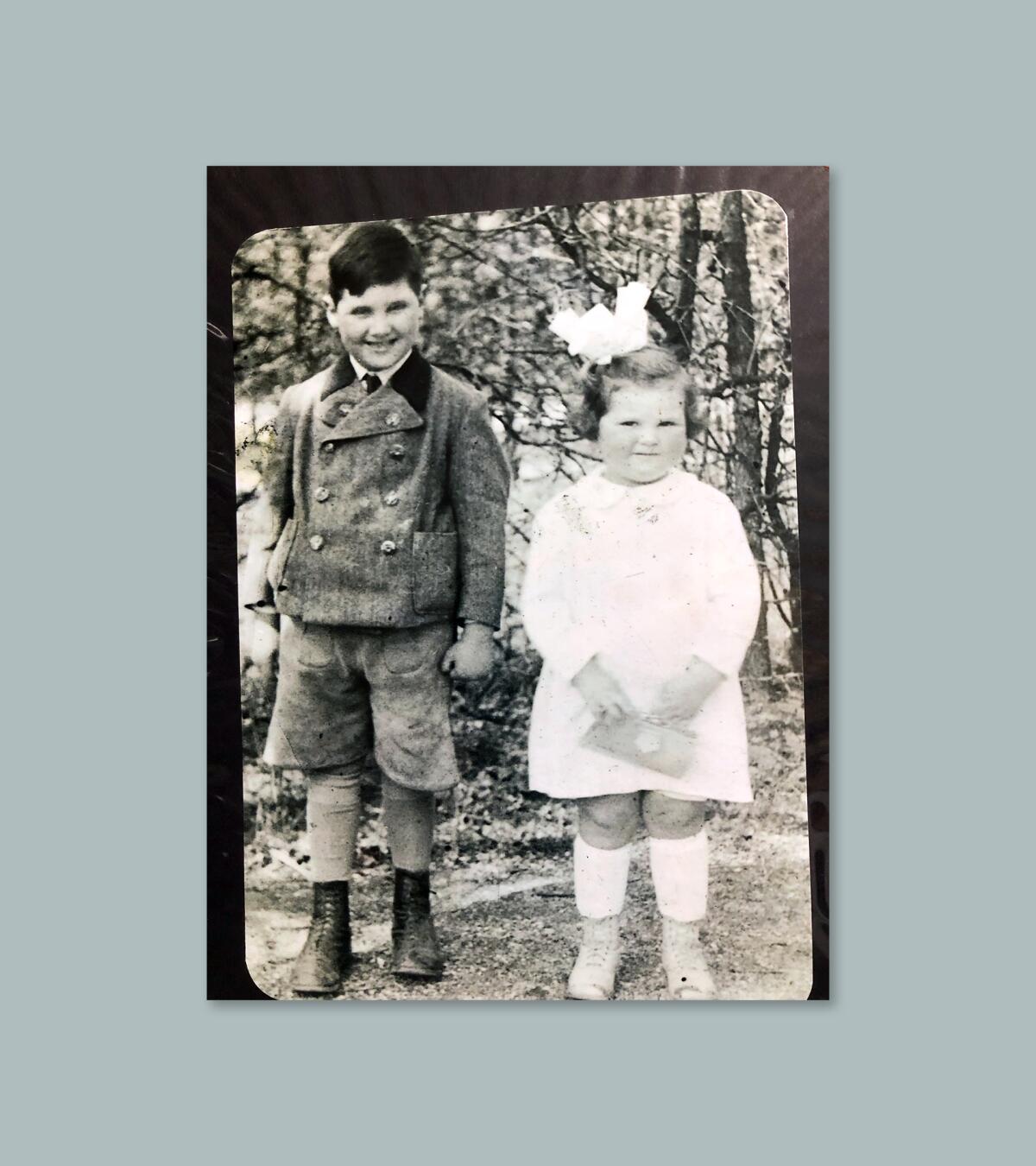

I am a proud American, born in Stettin, Germany (today, Szczecin, Poland) in 1933. My mother, father, sister and grandparents were all Germans of Jewish faith.

Because of Hitler and the Nazi regime, my family was forced to leave the country of our birth. We left behind my father’s family business, our friends and our home. My father was a highly decorated officer in the German army for his service during World War I. We were fortunate to be able to escape Germany and spared what so many others faced in the concentration and death camps.

My parents, my identical twin sister and I could not emigrate immediately to the United States because of a quota system that capped the number of Germans allowed to enter. So, we emigrated to England first and waited until we were legally able to come to the United States.

In June 1939, we arrived in the San Pedro harbor after a month-long voyage across the Atlantic and through the Panama Canal. My mother was 26 years old, with two 6-year-old girls. My father was in his early 40s and hard of hearing in one ear from an injury in World War I. We had no relatives or friends in California.

The Nazis forced the displacement of many of my relatives, who today live in India, Australia and Argentina. I relish and respect being a part of their lives even though we live far apart. It has made me humble and thankful for my life. My family was challenged with difficult times, and they turned their lives around with a positive attitude.

Much in today’s world concerns me. I sympathize deeply with refugees trying to flee poverty and violence south of the U.S. border. They want to come to the United States for a better life, but how can this country take in millions of people who would come here if they could? This is a difficult question to ask that is just as difficult to answer.

I am also concerned that fewer and fewer people are learning about the Holocaust. My father, mother, sister and I fled Europe before the mass killing began, and I have fond memories of our journey across the Atlantic, a period that my mother recalled as the best vacation of her life. But I also remember my mother and father begging their parents to flee. My grandparents died in the concentration camps.

My immediate family was not killed, but the Holocaust still happened to us. We lost everything we had in Germany and were forced to make new lives for ourselves. I feel it is important for people to know about this, the different ways Jews were victimized. Even though my parents did not talk about the Holocaust with us much at all, and though I am proud to be an American, I believe we must know about this history today.

Finally, I am concerned about a general loss of trust among people today. When I was a child, my father — a distinguished World War I veteran and proud German — had everything taken from him because the people were made to distrust and hate him and other Germans of the Jewish faith. Today, in our world, I worry about a similar erosion of mutual trust among the people.

— Betsy Kaplan, Covina

I write as a Jewish refugee from Hitler. My family fled Austria the day after the Anschluss of March 12, 1938. I come from an entirely secularized family, and my maternal grandfather was a leading diplomat from World War I to 1938. Nevertheless, the Anschluss meant that my family, by sheer dint of being Jewish by birth and ancestry, had to flee the country instantly, leaving everything behind. We left with four suitcases and no money. Those Jews who stayed behind, even for a few months, were likely to be sent to concentration camps and be killed in the gas chambers of the Holocaust.

But the currently popular comparison between the U.S. today and early 1930s Germany is highly dubious.

Unlike the U.S., Germany had no real tradition of democracy. Germany became a unified country only in 1871; it rapidly industrialized and became a major power by 1914. But until 1918, it was not only a monarchy but also an empire with a weak parliamentary structure. All government ministers were appointed by the Kaiser. The chancellor, moreover, could nullify any of the laws passed by the Reichstag (parliament). Then World War I decimated the country, bringing on large-scale poverty and, in the early years of the Weimar Republic, starvation. The 12 years of democracy from 1918 to the economic crash in 1929 were already shaky by the time of Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch in 1923.

Then, too, 21st century Americans ignore the role communism played in bringing the Nazis to power. In 1930, there were 37 individual parties running for office. If the Socialist (SPD) and Communist (KPD) parties had joined forces, the Nazis wouldn’t have had a chance. But because the SPD and KPD were constantly at each other’s throats, the far right saw its chance.

It is impossible to understand today how great the fear of Russian communism was. It would have meant giving up private property — i.e. your house and home. This is hardly equivalent to the “threat” from the Republicans today. Those who turned to the Nazis often regarded it as the lesser of two evils — a temporary state of affairs before a centrist party could win again.

The day Hitler became chancellor, the free press simply dissolved; from then on, all newspapers reported directly to Hitler. In the U.S., on the other hand, every major news outlet with the exception of Fox was adamantly against Trump throughout the four years of his presidency and continues to be obsessed with calling him every name in the book. Even NPR and PBS seem to be 100% pro-Democrat. So where is the parallel?

What comparable state of affairs exists in America? Instead of the Weimar splinter parties, our current moment is Manichean, the country being divided right down the middle. Each of our two parties thinks it is the democratic one and the other elitist, racist or sexist.

And consider the anarchy today! At the moment, schools seem to be barely functioning; some close regularly because there are not enough teachers. This is the antithesis of Hitler’s Germany, where regimented children, marching into the classroom, were indoctrinated into fascism. For Hitler, discipline was the order of the day, whereas the Trump administration was curiously disorganized, firing its own personnel left and right. At the same time, the Biden administration seems to be paralyzed when it comes to education.

Finally, it should be made clear that democracy is not just a voting issue. One can, after all, vote in, fairly and squarely, a fascist party. It has happened all over Latin America. Rather, as Alexis de Tocqueville warned, democracy only works when you have a reasonably educated public. Today, when we have eighth graders who can’t read and write, when civics courses have disappeared and when geography is literally untaught, it is very hard to have a meaningful democracy in the U.S.

Our first aim should be to restore primary education as well as a meaningful media in which there is real discussion of the issues. As for antisemitism, how can it be avoided at the same time Israel has become such an object of hatred?

— Marjorie Perloff, Pacific Palisades

I am a Holocaust survivor and an American. I was born in Vienna six years before the annexation of Austria by Hitler’s Germany. My family was very affluent — we lived in a large apartment and had several servants. I was a very spoiled brat.

Everything changed in March 1938, the date of the “annexation.” No shots were fired, nor were there protests. German airplanes dropped leaflets advising us not to resist. Hordes of Austrians happily donned German uniforms sporting the swastika.

Several days later my father was physically thrown out of his business. His assets were confiscated. Soldiers came into our home and took anything they deemed valuable. My school, across the street from where we lived, was closed.

One day I heard gun shots and screams. I went to the window and saw maybe 30 ultra-Orthodox men dressed in their traditional garb doing exercises in the middle of the street. Some were very old. They were surrounded by soldiers. If they stopped or sat, the soldiers would prod them with their guns. If they did not get up, they were shot.

There were food shortages. Jews were not allowed in food lines. We were hungry.

One day I had an accident and sliced my knee open. My father wrapped my leg and took me to the local emergency room, where we were refused admittance because of the large “J” stamped on our identification cards. Somehow (I was unconscious), my father found either a medical school or a small hospital on the outskirts of the city, and a kindly doctor risked his life to operate on me.

On Kristallnacht — Nov. 9, 1938 — the Nazis determined to kill as many Jews as possible. My parents knew they would be coming for us. A banging on the door did not startle us. The door was opened and there stood a Nazi officer and a soldier. The officer yelled, “Quickly, come with us!”

My mother had secreted some jewelry. She gave it to the officer. He took it and hesitated, then turned and yelled at the soldier to go to the next address.

Shortly thereafter the Gestapo occupied the building as its headquarters. Our apartment was about five steps to the right of the entrance between floors and not accessible to the elevator. They left us alone, and we spent the rest of the time in the Gestapo headquarters building.

For 84 or 85 years, these memories buried themselves in the back recesses of my brain. Jan. 6, 2021, caused a tsunami of memories to come back to the forefront.

Terror, insecurity, fright — will America’s Constitution and freedoms be overturned? Will we become a dictatorship?

Tyrants thrive on chaos, incitement to overthrow government, fraud, mass hysteria, lies, manipulation and rallies. That is their playbook. I can still hear Hitler’s rallies with thousand yelling “sieg heil,” until our radio was confiscated. Will the legislators who have blatantly ignored their oath of office let their conscience guide them?

I instructed my children to always keep their passports current and to keep their assets only in banks that transfer money to foreign institutions via wire transfers. My insecurities are due to my history.

Yet, I have faith in America and that the so far silent majority will be able to protect our country.

— Marianne Bobick, Gainesville, Ga.

Never-before-seen footage of the chaos during the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, from Los Angeles Times photographer Kent Nishimura’s GoPro.

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.