Did California issue its last fracking permit? Let’s hope so

- Share via

There’s been a welcome development in California’s fight against climate change: Regulators are saying no to the oil industry.

Earlier this year, state oil and gas regulators quietly began denying hydraulic fracturing permits on climate change grounds, without waiting to finish regulations to ban fracking by 2024 that Gov. Gavin Newsom has ordered. Since July, the state Geologic Energy Management Division has denied 109 permits sought by oil companies to use hydraulic fracturing or other well stimulation methods, and in 50 of those cases has cited the impacts on the climate and public health.

California has not granted a fracking permit since February. So if the streak of denials continues, it’s possible that will be the last one ever issued.

Let’s hope so. California needs this kind of decisive action, and more of it, to help slow the heating of the planet and do right by the communities near drilling operations, which are disproportionately Black and Latino, and have suffered the health impacts for far too long.

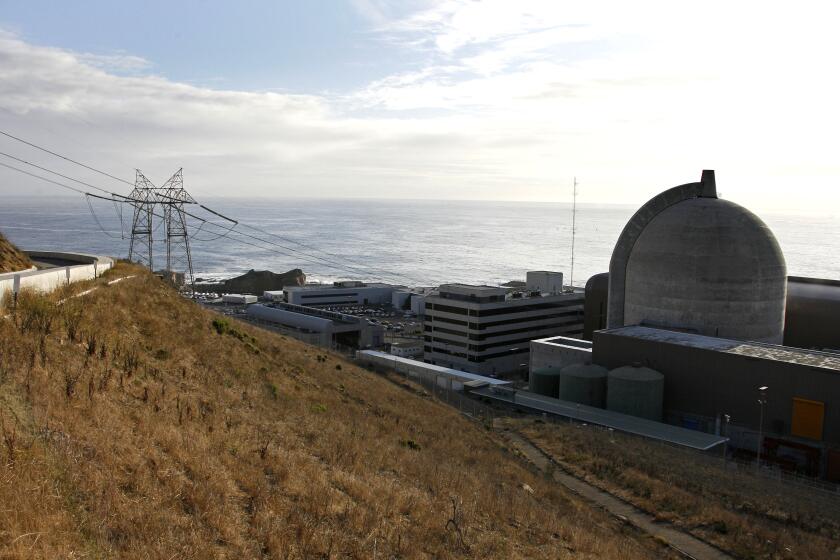

The impending closure of Diablo Canyon shows the need for California to double down on renewable energy and accelerate the transition.

In one letter to Aera Energy, State Oil and Gas Supervisor Uduak-Joe Ntuk put the permit denials in the context of deadly heat waves, devastating wildfires, intensifying drought and the need to rapidly decrease fossil fuel extraction to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

“Given the increasingly urgent climate effects of fossil-fuel production, the continuing impacts of climate change and hydraulic fracturing on public health and natural resources,” Ntuk wrote, he “could not in good conscience” grant the company the permits it sought.

A California law that took effect in 2014 requires additional review and permitting for hydraulic fracturing, which involves injecting a mixture of water, sand and chemicals underground at high pressure. But the state had never actually denied a fracking permit until last year.

The denials have prompted lawsuits, including one filed in Kern County Superior Court by the Western States Petroleum Assn., which calls it a “de facto moratorium” on well stimulation permits and says the applications were improperly denied. But as regulators point out, state law gives them discretion over fracking permits and they are not obligated to approve them.

What oil interests really fear is the end of oil and gas production and the elimination of their industry in the state.

The sculpture of a fossilized gas station at California’s new emissions testing lab in smoggy Riverside? The symbolism is perfect.

But the science is clear: To avert catastrophic climate change we must phase out the extraction and burning of fossil fuels and shift rapidly to emissions-free energy sources. These permit denials affect a small amount of California’s overall oil production, only 2% of which involved hydraulic fracturing in 2020, and the extraction method is almost exclusively limited to Kern County, according to state officials. Nonetheless, it’s encouraging to see the Newsom administration use permitting as a tool to keep more oil in the ground.

So what’s stopping his administration from going further and turning down more oil industry permits because of the threats to the climate and our health? The state has issued 517 new oil and gas drilling permits since February, projects that will also increase pollution and heat the planet.

Officials argue that broadly rejecting drilling permits and stopping so much production at once would be too big of a jolt to the state’s still overwhelmingly fossil-fueled economy. Though Newsom’s administration is evaluating how to end oil extraction by 2045, in-state production still accounts for about one-third of California’s oil supply. So for now, regulators are targeting fracking, which is one of the most intense types of extraction, and drilling operations close to homes and schools.

Newsom has had a somewhat confusing evolution on the issue. In 2019 he fired the state’s top oil industry regulator for issuing too many fracking permits, then his administration stopped granting them while conducting scientific reviews, only to start again. Last year Newsom asked state legislators to send him a bill to ban fracking, insisting that he lacked the executive authority. But after legislative efforts failed, he announced in April that his administration would move forward with regulations to ban fracking by 2024. His administration is also now developing rules to prohibit new oil and gas wells within 3,200 feet of homes, schools and healthcare facilities, measures that are also moving forward administratively after legislation died amid opposition from the oil industry and its allies in organized labor.

Newsom is right to forge ahead when state lawmakers will not act to protect public health and the planet. California is still not doing nearly enough, but at least the governor seems to be waking up to the idea that even relatively small actions, like saying no to oil companies, cannot wait.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.