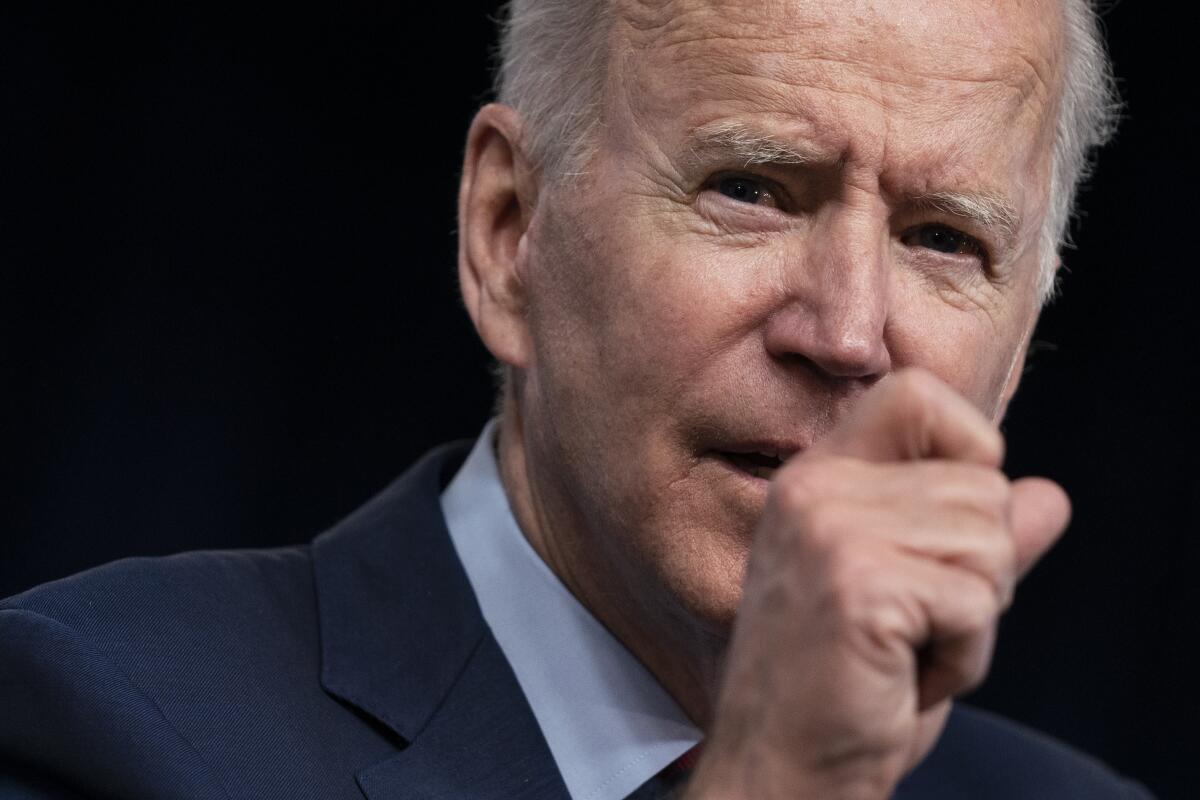

Opinion: The Biden administration makes a disappointing decision on refugees

- Share via

The decision by the Biden administration to delay ramping up resettlement of refugees — all but halted under his predecessor — is a sore disappointment, particularly to the tens of thousands of people hoping to start news lives here in the U.S. But the political and logistical realities are hard to deny.

President Biden earlier told Congress he would raise President Trump’s cap of 15,000 refugees per year — a low in the nation’s modern history — to 62,500 this year, and increase it further to 125,000 next year.

But then two realities intruded: The refugee resettlement system was gutted by Trump administration policies, and the sharp increase of children and families at the U.S-Mexico border has strained resources and muddied the politics.

The Times editorial board earlier this year laid out the problem with the resettlement system. In a nutshell, the non-government agencies that do the actual resettling are funded primarily by per-refugee payments from the federal government. When the Trump administration slashed annual resettlements from the Obama administration’s 2016 cap of 85,000 to 15,000, that meant the floor fell out for the resettlement programs themselves. (There are proposals for fixing that funding problem.)

The court’s senior Democratic appointee warns about court-packing.

So there’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario here. To significantly increase refugee resettlements, we need a stronger and more resilient resettlement system, but to rebuild that under current rules, we need more refugees resettled.

Nevertheless, some of the resettlement organizations say they have plenty of capacity to handle more resettlements.

“Officials have now suggested that capacity constraints have compelled them to maintain the current ceiling,” said Eric P. Schwartz, president of Refugees International. “That suggestion is without merit. Government agencies and the voluntary organizations that assist in resettlement have substantial capacity to resettle far more than 15,000 individuals this year.”

An ACLU official also condemned the decision.

“We know that this system cannot be rebuilt overnight, but today’s order reflects abysmally low numbers that will exacerbate suffering all over the world,” said Manar Waheed, senior legislative and advocacy counsel. “Today’s news is a devastating blow to Black and Brown immigrants who are fleeing persecution and seeking refuge — and have been for years — only to see their hopes destroyed by an administration that promised to do better.”

Biden’s press secretary, Jen Psaki, said Friday afternoon that the administration intends to “set a final, increased refugee cap for the remainder of this fiscal year by May 15,” but didn’t indicate whether it would be close to the original goal.

Meanwhile, the government is trying to deal with a surge of asylum-seekers primarily from Central America. Note that refugees and asylum seekers, while hoping for essentially the same thing, move on two separate tracks.

Refugees typically are first vetted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which makes the determination whether permanent resettlement is in the refugees’ best interests (usually because they have no safe home to return to). Then, after checking their backgrounds, the commission refers them to specific countries.

Those referred to the U.S. then face a second round of vetting, while still overseas, by State Department and U.S. Customs and Immigration Services interviewers who explore whether the applicants meet criteria for protection, such as facing persecution in their home countries for religious or political beliefs.

Once accepted for resettlement, the government fronts the cost of transportation and connects the refugees with the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which works with the non-government groups to find people places to live, jobs, etc.

Asylum seekers, on the other hand, apply for sanctuary primarily while in the U.S. or when they arrive at the border seeking entry. They go through an entirely different process that often involves immigration court proceedings. So the staffs are, for the most part, different. But since the closing of refugee resettlements, the government reportedly has shifted a lot of the folks who handled refugees to help process asylum seekers.

Yes, a management nightmare.

The Amazon organizing drive spotlights unions’ bigger problem: persuading Americans exactly how vital they are to our working lives.

And there’s the politics. Biden has come under fire from conservatives and immigration hard-liners who accuse him of encouraging migrants to come to the U.S. by reversing Trump’s broadly inhumane, and often racist, immigration policies — in particular, by allowing unaccompanied minors, and in some cases families, to enter the United States rather than forcing them back into unhealthy and dangerous areas of Mexico.

So the administration seems to have decided not to fight the war on two fronts. And while it is reconfiguring the map of where the limited number of refugees can come from, it has still just left the door ajar, and not opened it on the scale that some previous administrations had done.

So it’s disappointing. As The Times editorial board wrote in February:

“As one of the world’s wealthiest countries (despite our internal economic disparities), we have a moral obligation to help others. We are, by and large, a generous society, though we often squabble over how best to act on that generosity and who deserves to receive it. No, we are not obliged to accept all the world’s dispossessed people, but the U.S. ought to serve as a global role model for how nations should respond to humanitarian crises. It is no small responsibility to be the beacon of hope for those facing despair.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.