Op-Ed: Does ‘Nomadland’ reveal the reality of working for Amazon?

- Share via

Here are some of the memorable moments from “Nomadland”:

Chuck Stout, working at an Amazon fulfillment center as part of CamperForce — temp workers, mostly on the older side, who show up in vans and RVs to help with the holiday rush — is stationed near a conveyor belt when a box flies off, knocking him down and causing his head to hit the concrete floor.

Laura Graham is struggling to keep up with the countdown that begins on her handheld scanner every time she scans one product and is expected to pick another one. When she loses five minutes after accidentally turning into the wrong aisle, a supervisor comes to scold her for her delinquency.

Linda May suffers such a dizzy spell in a warehouse that she is taken to the hospital. She also suffers a wrist injury that will linger for several years from the repetitive motion of the scanner. She struggles, too, with the whole purpose of the job, of being “a cog in the world’s largest vending machine.”

If you don’t recall these scenes from “Nomadland,” the powerful Chloe Zhao film nominated for a slew of Academy Awards, that’s because they’re not in the movie. They are, however, in the 2017 nonfiction book by Jessica Bruder of the same title, which lays bare a subculture of older Americans struggling to make their way in a country that has cast them aside.

The film, adapted from the book, captures that world with arresting visuals and the affecting story of one fictional nomad, Fern, played by Frances McDormand. Strikingly absent, though, is the book’s depiction of the grim work at Amazon fulfillment centers.

While Amazon casts a shadow throughout Bruder’s book as a recurring employer of the nomads, the film includes only a couple segments inside a warehouse. And while the fulfillment center is gargantuan and antiseptic, there is nothing particularly unpleasant about it.

We see Fern packing boxes with bubble wrap and stowing products on shelves, and smiling at other workers. We see workers taking a friendly lunch break. We see Fern, when asked about the job, declaring that it’s “great money.” Later in the film, when she returns for another Christmas-shopping season at a warehouse, it feels almost like a homecoming.

The visual power of the film and its emotional core, Fern’s grief over the loss of her husband and her former life, occupy the audience’s attention, not Amazon’s problems. One could easily come away from the movie having a benign view of the toll Amazon takes on its workers, including the temporary ones.

As Alison Willmore explained in her profile of Zhao in New York magazine, Zhao believes Amazon “is an easier villain than the structural issues that enable CamperForce to exist, which is why she filmed the warehouse scenes the same way she did the scenes of Fern cleaning toilets on a campground and shoveling beets in Scottsbluff, Nebraska.”

It is certainly true that the older Americans who populate “Nomadland” — both in the book and the movie — are victims of all manner of larger forces, including age discrimination, wage stagnation, the fraying of the safety net, and the fragmentation of the American family.

But, as Bruder’s book shows and as I found in my reporting on Amazon, one can both take into account larger structural issues and hold the company accountable for specific actions that have made matters worse for its employees.

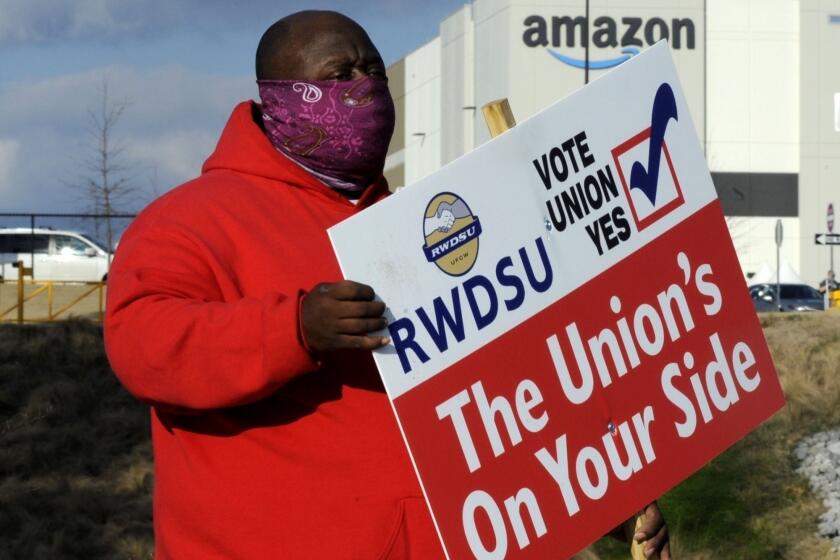

The organizing in Alabama could set off a chain reaction across its operations nationwide, with more workers rising up and demanding better working conditions.

Bruder’s book offers many such examples. There is Amazon’s practice of making workers spend many unpaid minutes going through anti-theft security checks after their shifts. There is the “wall of shame” showing anonymous profiles of employees who have been caught stealing, including one who consumed $17.46 in food intended for warehouse shelves. There are the degrading drug tests. There are the company’s warnings that it will keep a permanent record of any engagement with union organizers outside one Texas warehouse.

Above all, there is the relentless pressure to meet targets. “People were going around just like insane,” one product stower tells Bruder. “There was nowhere to put anything, you wanted to beat your face against a wall.” Meanwhile, Bruder writes, “supervisors were telling them to pick up the pace, to make ‘rate,’ that ‘we’ve gotta get our numbers.’”

Conditions have, if anything, gotten worse during the pandemic. The huge surge in orders, which helped drive Jeff Bezos’ wealth up $58 billion over the past year, further ratcheted pressure on workers. And belated measures to slow the spread of the coronavirus in the warehouses made the job even harder — for example, jobs once assigned to two people were now done by one, for spacing reasons.

Workers in the Amazon warehouse, in Bessemer, Ala., are taking more concrete action: holding a union election that will be decided this week. It’s a response that one could easily understand based on reading “Nomadland,” but less so from watching the movie.

Alec MacGillis, a reporter for ProPublica, is the author of “Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.