Opinion: Reading poetry under lockdown is easier than baking sourdough. And it’s healthier

- Share via

Can poetry save our sanity during the pandemic? Or, at least, distract us? I’ll let you know after I moderate a panel of accomplished poets Thursday night.

In a time of need for solace, poetry is the most rarefied form of distraction. It’s not a movie, a novel with a digestible narrative, a jigsaw puzzle (although, frankly, jigsaw puzzles only annoy me). It’s not bread-making or cocktail-mixing. It’s not about a craft. It’s some hybrid of reading and surrendering.

I agreed to moderate the panel precisely because I didn’t know what to expect, didn’t know how I would be affected by these poets’ words.

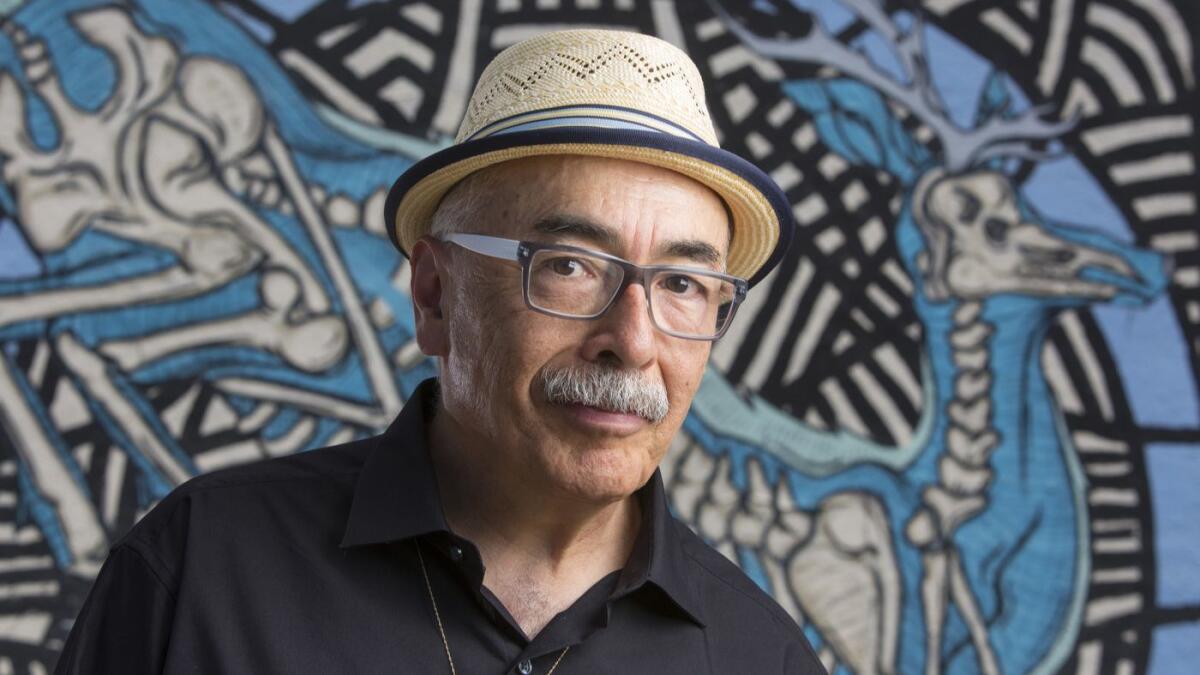

One of the panelists, Juan Felipe Herrera, the former California poet laureate and the 21st U.S. poet laureate, has never shied away from writing about the violence and the fear that confront people of color born here and people of color trying to get here. But, in the pandemic era, he’s also embraced the moment, writing in his poem “Social Distancing” that “grocery bags have a tendency to wobble.” His poem has a layout: words embedded on what look like spokes of a wheel flaring out from a center.

When I wrote an email to this distinguished group, which also includes Alberto Rios, and Inez Tan, suggesting some questions we should address Thursday night, Herrera wrote back to give me the go-ahead. In a poem. It read in part:

Any of these questions and those that spring

Up out of everywhere...

Poetry hugs

I’ve never had anyone write me an email in verse — well, except for a good friend I invited to Zoom in to this poetry event, who declined with this note:

While it’s always fun and a ball

To see our beloved Carla Hall

I don’t have the time

For poems that don’t rhyme

Right, this is not Dr. Seuss. (Not that I don’t love Dr. Seuss.) Alberto Rios writes about sensuality and love and family — and rabbits and death in the fires that ravage the Sonoran desert. Inez Tan writes about fear and annoyance and the struggle to create:

We all chant our own little spells hoping hope will make them work.

When I first read some of their poems, I could feel my mind racing, careening around the jerky, seemingly disordered words, demanding there be a theme, but I came to the end and was left thinking, “Wait, what?” So I would start over, slow down, and listen to each word as images came to mind and the poem revealed itself to me. It’s the closest I’ve ever come to meditation. And although I hate traditional meditation, who doesn’t crave something that transports you away from death tolls and hand sanitizer?

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.