Readers React: Breast cancer experts: Mammograms aren’t perfect, but women should get screened

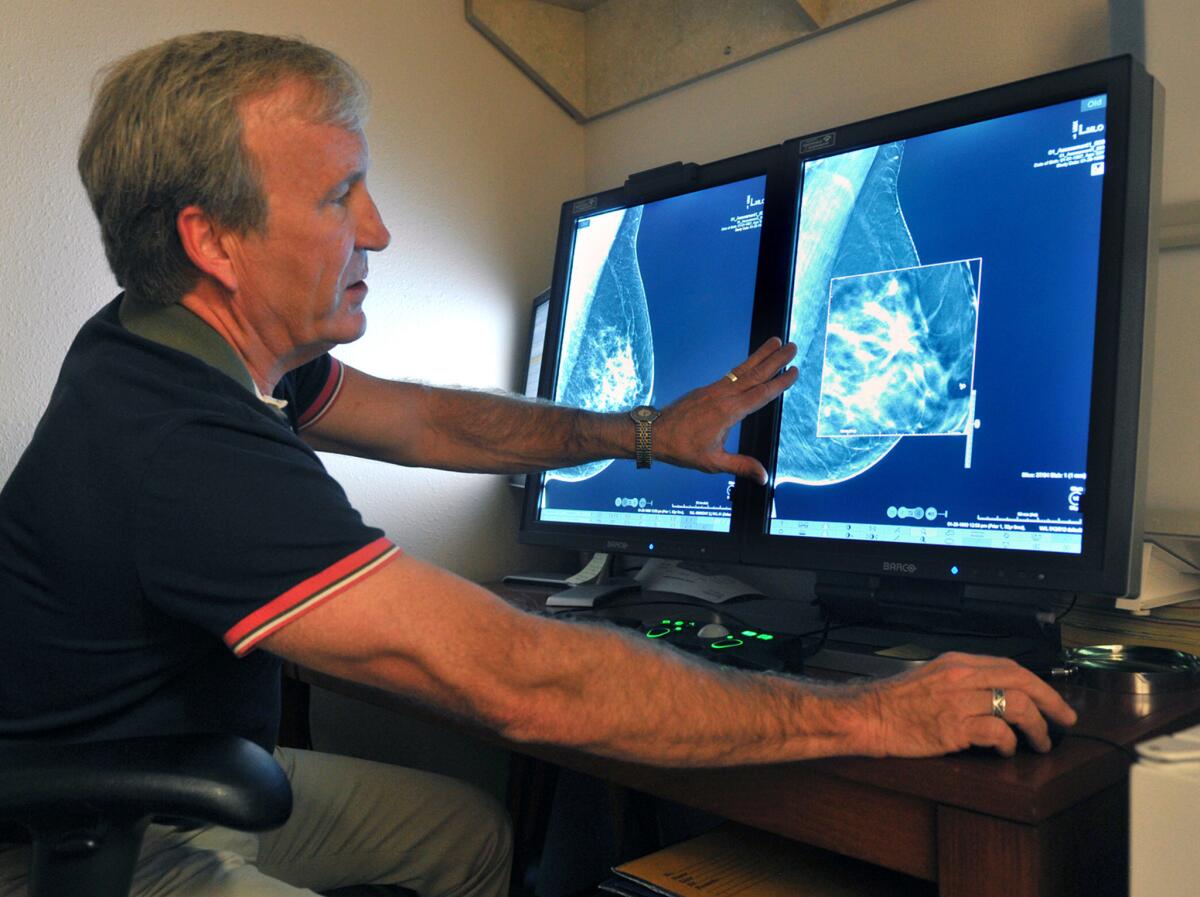

A radiologist compares an image from an earlier, two-dimensional technology mammogram to the new 3D mammography. The technology can detect much smaller cancers earlier.

- Share via

Whenever The Times publishes a piece raising questions on the efficacy of regular mammograms for women over 40 (or any cancer screening or treatment, for that matter), we typically receive several impassioned letters to the editor from cancer survivors or patients currently undergoing therapy who say they owe their lives to early detection methods.

That reaction is understandable and welcome. For these people, abstractions about the usefulness of treatment or screening methods over large populations are highly personal in a way they aren’t for the rest of us. Their stories of surviving cancer ground debates over efficacy and best practices in real-life, human experiences.

We’ll also hear from a few experts who reject whatever contrarian medical opinion has been proposed. Mostly, these reactions read as dispassionate reminders of the consensus on the treatment and detection of cancer.

Similar to part articles on the subject, both cancer patients and physicians responded to the op-ed article Sunday by Dr. H. Gilbert Welch questioning whether regular screenings for breast cancer actually help women. But this time, it was mostly the doctors who reacted in greater numbers and more harshly to Welch’s piece than the patients.

One disapproving letter from a cancer survivor and another from a doctor were published online and in print this week. Since then, several more physicians — many of them experts in breast imaging — have sent us their letters. Their reactions range from clarifying the opinions held by the majority of physicians who treat breast-cancer patients (they say women should still get screened regularly starting at age 40) to questioning Welch’s science and motivation.

Here are some of their letters.

Dr. Kenneth Offit of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City says mammography, though imperfect, is an important tool in fighting breast cancer:

While Dr. Welch raises important questions regarding breast cancer screening, the vast majority of cancer care physicians endorse screening when our patients ask us whether they should have mammograms. We remain impressed by the evidence that mammography screening saves lives.

As observed in the editorial accompanying Dr. Welch’s most recent scientific publication, it remains impossible to predict when an individual mammogram will result in “overdiagnosis” of a cancer which might never progress. While newer methods of risk assessment using genomic and other markers should allow adjustment of type and timing of breast cancer screening, until then, mammography remains a reliable and proven means to detect cancers at their earliest, most curable stage.

Dr. Dana Smetherman, a radiologist in New Orleans, says finding those “small breast cancers” is precisely the goal of screening:

Dr. Welch is correct that “over time and over place, the findings are consistent: Screening is good at finding small breast cancers.” This is actually the goal of screening — identifying early-stage disease when it is most likely to be cured with the least aggressive treatment.

As noted by the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the number of lives saved from death by breast cancer is maximized when annual screening mammography begins at age 40. Suggesting that women cannot judge for themselves whether “harms” (like anxiety) from a false positive outweigh the risk of dying from breast cancer smacks of paternalism.

Also, stating that women are treated for cancers that are “not destined to cause symptoms ... or be life-threatening” wrongly implies that doctors can currently predict which cancers will become lethal.

Dr. Daniel Kopans, a Harvard radiology professor and the director of breast imagining at Massachusetts General Hospital, says mammogram naysayers unnecessarily risk women’s lives:

Dr. Welch’s op-ed article contains too much misinformation to address in this small space. One of a very small group who do not actually provide care for women with breast cancer, he is trying to reduce access to screening based on flawed analyses that have crept into the (less than perfect) medical literature. The vast majority of experts agree that therapy has improved, but therapy saves the most lives when breast cancer is treated early. The evidence shows that the most lives are saved by annual screening beginning at the age of 40.

Welch shows a disturbing lack of fundamental knowledge. Once a woman has a “lump,” it is too late. The mammogram is used, primarily, to screen the rest of the breast and the other breast for unsuspected cancer.

Invasive breast cancers do not disappear on their own (overdiagnosis). No one, including Welch, has ever seen this happen. His paper, to which he refers, has been shown to have been based not on science, but as his coauthor admitted in writing, “best guesses.” Healthcare advice should not be based on “best guesses.”

The recall rate for follow-up treatment after a mammogram is the same as for cervical cancer screening (10%), requiring a few extra pictures or an ultrasound. To reduce anxiety and inconvenience, Welch would effectively take away a woman’s right to decide for herself and would allow some to die unnecessarily by limiting access to screening.

Mammography is not perfect, but there is no universal cure on the horizon. Thousands of lives are now being saved because of early detection. Women need the facts and not a misguided crusade to take away their access to screening.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.