Column: Patt Morrison asks: Historian Douglas Brinkley talks Clinton, Trump and the history of political conventions

- Share via

For the next couple of weeks, we’re being treated to the biggest show this side of the Atlantic -- the national presidential nominating conventions, our two-week, two-party festivals of red-meat speechifying and hats pimped out like parade floats. How, from the loftiness of President George Washington, did we ever get to this? Douglas Brinkley, who’s written books about Presidents Reagan, Ford, and both Roosevelts, among other volumes, is there for both conventions, and here he takes a lap around conventions that were and might yet be.

CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THIS INTERVIEW ON THE ‘PATT MORRISON ASKS’ PODCAST»

The Constitution doesn’t even provide for political parties, much less political party nominating conventions. How did we get to this?

The Founding Fathers were very worried about the two-party system, so much so that in 1800, when Thomas Jefferson was warring with John Adams and each was just beating up on each other in the press, the head of the former Continental Congress, a man named Charles Thomson, burned the founding minutes of our country, because he said we’ll never be able to survive if these elections are this brutal if we don’t all get behind a president once they’re elected.

So what Thomson’s point was, we’ve got to make presidents a cult so once they win we get behind them. That’s how our Capitol is Washington, D.C., and we have presidents on our currency, and we define our eras as the Reagan years or the Obama years.

The first political nominating convention, I think, was in 1832 with the short-lived Anti-Masonic Party – not around much longer.

There became some interesting parties like the third parties, as we call them today; the Know-Nothing party in the 19th century was anti-Mormon and anti-Catholic, and of course you have third-party movements. The Bull Moose party in 1912 with Theodore Roosevelt was the most successful third-party movement. But by and large, we are now, since the Civil War, it’s about being a Republican or a Democrat, and we usually only have two real choices. This year, the Green and the Libertarian Party might end up playing spoiler roles in a close election.

Pretty early on, the parties thought, we should get our act together and make this work like a well-oiled machine.

I think that the big turning point was the advent of television. In 1952, when Taft, Robert Taft, and Dwight Eisenhower were fighting for the Republican nomination, CBS brought cameras into that process and it was very boring and ugly – it was some smoke-filled rooms, wrangling and wheeling and dealing, it didn’t look visually great. And after ’52, both parties started recognizing that the conventions have to be coronations, that they have to be choreographed.

And so you get the birth of not just the telegenic candidates but also the idea that the sausage factory of politics takes place during the primary and caucus season, but by the time you get to the July conventions, they’re at least inside the arena … supposed to be very scripted.

But of course as we know from Chicago in 1968, what goes on outside the convention sometimes can be very disruptive and harder for a political party to control.

The process of caucuses and primaries being so criticized now was actually a great step forward in reform from those smoke-filled rooms.

I do think the primary and caucus system, with all of its problems -- it generally works. The downside about it is we seem to be in permanent running-for-president mode, and that is raising some eyebrows. Why are we spending billions in this long a process? Isn’t there a way to shorten it? But every time people talk about that, it’s like saying, let’s get rid of the electoral college. It’s good for an op-ed piece in a newspaper, but in the end, we keep doing what we’re doing right now.

We try to avoid contested conventions because it’s just not good for the party. However, this year, with Donald Trump being such a polarizing figure, there were people praying for a contested convention, hoping Trump wouldn’t be able to amass enough delegates. Whether you like it or not, it’s going to be Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

The big thing is who will be the vice presidential nominees? It is the only drama left. The vice presidents, many do become president. Just look at since World War II: I mean, Nixon was Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president, and Johnson was Kennedy’s vice president, and George Herbert Walker Bush was Reagan’s VP. It is the quickest route to becoming president, being vice president.

Some of the notable conventions: the 1924 Democratic convention with more than 100 ballots, and I think the one that for most people dwells in memory is 1968 in Chicago. You had protests in the streets of Chicago as Chicago police were beating protesters who were yelling, “The whole world’s watching,” and inside the convention, you have the senator, Abe Ribicoff, and Mayor Richard Daley, nominally from the same party, going at each other.

Oh, it’s an unbelievable spectacle, what happened in 1968. It was just mayhem in the streets. And inside, even Dan Rather, who was working as a reporter for CBS, got roughed up within the convention. So we talk about conventions that didn’t work well; Chicago is the one that comes to mind.

Some of the stars of tomorrow, meaning future presidents, may be on hand in Cleveland and Philadelphia, but however many Republicans are kind of boycotting Donald Trump, they don’t want to be seen there, they don’t want to be seen in the photo ops with their party’s nominee, and that in itself is quite bizarre.

I mean, Gov. Kasich of Ohio is saying he won’t even go to his own convention. He doesn’t want to be contaminated standing next to Donald Trump. I haven’t seen that before, where people of a major political party are embarrassed to be seen with the candidate.

The 1964 convention in San Francisco, where moderate Republicans battled with Goldwater Republicans -- it was vehement and even ugly on the floor of the convention at the Cow Palace. President Eisenhower said it was “unpardonable.” He said he was “deeply ashamed” by what he was seeing.

You just picked a very important one politically. Not only did protesters go after the opposition there, but they were booing and hissing and threatening reporters. Trump has gone after the media so hard and sometimes by name that they may be bullied, harassed, denunciated, because Trump has made journalists enemies, that’s part of his plan: Everything he does is the media’s fault.

You mentioned speeches by future candidates, but have there been any great convention speeches by the actual candidates? The only one that comes first to my mind is William Jennings Bryan in 1896, his “Cross of Gold” speech as the Democrats were split.

I think Obama’s was good in 2008. They’re all very well written, but they’re so choreographed that you’re not making a speech as a president, you’re simply a candidate, and most of these become their well-honed speech.

For example, Bernie Sanders has a very fine speech he delivers -- he’s done it hundreds of times, and it allows him to perfect it. But they’re kind of set speeches, almost, by the time they get to conventions.

And in this case, you don’t want to be usurped. If you’re Donald Trump, you don’t want someone out-delivering on oratory. You don’t want to be seen as second fiddle. When FDR got polio and he ended up endorsing Al Smith of New York [in 1924] in Madison Square Garden, FDR was in a wheelchair. Al Smith thought, “Well, I’ll have him give the convention speech” – and FDR stole the house. He got a one-hour standing ovation. And the next day, the New York Times said, Forget Al Smith: Franklin Roosevelt is the new political star.

You used the world infomercial, and so did Ted Koppel.

You know who was the first one to really say that, before Koppel, was Edward R Murrow. He said, I’m a journalist, I don’t want to be used by political parties. Now he changed, he showed up to do some broadcasting in 1960 in Los Angeles, when John F. Kennedy got the nomination, but Murrow’s point was, we’re being manipulated and reporters shouldn’t be that.

Nevertheless, I work with CNN as the presidential historian, and these are big ratings moments for cable TV and the networks. You’re hoping everybody tunes in, and it’s a big commercial ad buy time, and also the summer months – it’s sort of a dead zone, the summer season. Journalism, particularly television, has become big business, so anything they can do to attract a lot of voters.

Trump has claimed, “I’m going to make this an entertainment festival, more rock bands, more comedians.” I don’t know how many rock bands and comedians want to tie their kites to Donald Trump, but his attempt is to make it a kind of casino-like show. It’s all become entertainment in some ways.

Then there is the unexpected dramas in Cleveland. People were planning to protest for months. I think the camera action on what’s going on outside the convention hall is really going to be more interesting and also more dangerous than what’s going on inside.

Well, what do you think is going to happening inside?

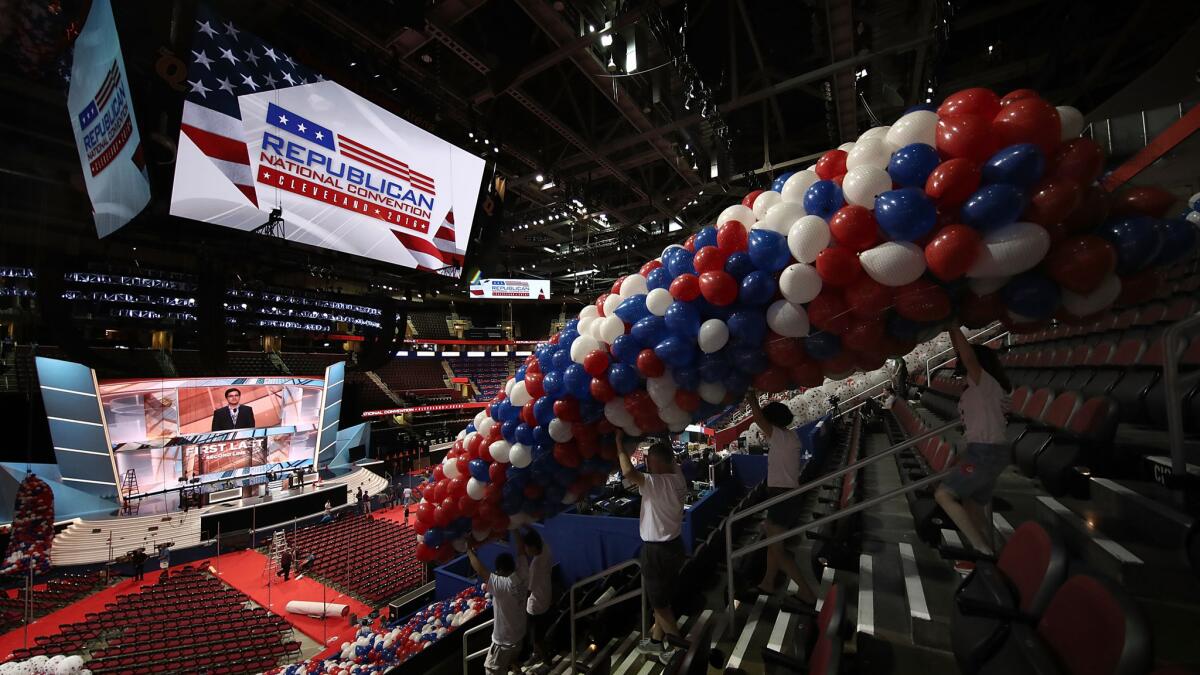

Here’s the problem the Democrats face – boredom, that it doesn’t become like one big C-SPAN show. People now are living in such a hyperkinetic media zone all the time that if this just speechifying red, white and blue balloons coming down and everything seems calm in Philadelphia, they’re not going to want to watch it. Where in Cleveland, the spectacle of Trump and the street carnival that is expected there may conversely and also perversely draw more viewers. It’s kind of like the car crash: I want to watch to see what bad‘s going to happen.

Is there any possibility, are the Republicans concerned that Cleveland 2016 could be their equivalent of Chicago 1968?

Big time. That’s what the problem is. There’s only so much Cleveland security can do. It’s going to be how many protesters show up.

And it’s the armed confrontation; you’re kind of feeling the police arm and on one side there are these Trump supporters, and on the other side are Black Lives Matter or the progressive movement. And that mixing on the street, as we see it just takes one incident to start a riot, and at all cost Cleveland’s doing their best to try to prevent that.

It can be done, but just one or two angry kooks can really make mayhem, you know, anarchy.

You mentioned the immense impact of television on the way the conventions are conducted. What about the impact of social media, which has been emerging in the last half-dozen years?

Giant. Let’s say Philadelphia, if there’s some event that occurs outside of the convention hall, there are now people outside the convention hall who are going to take pictures. Well, previous eras, nobody has a picture of that. The cameras are inside the convention. Now, if there’s a real riot, obviously cameras will get trained on it. But now, every little strange photo will start appearing on television and throughout social media. So it could escalate things, because you know what used to be missed by the cameras are now being picked up by people’s cellphones.

That, I think, makes the world more interesting. But it also has the chance that one photo of a policeman hitting someone with a billy club could end up really creating more problems than it normally would.

If you had the chance to go watch any political convention since that first one in 1832, what one do you think you might want to go back and spy on?

Boy, what an interesting question. I would have liked to have been in Los Angeles in 1960 when John F. Kennedy, the youngest elected president, was able to take away the Democratic nomination from people like Lyndon Johnson and Stuart Symington and Hubert Humphrey. The fact that Kennedy was using television, it was to my mind the beginning of a new era. So that’s the one I would pick.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.