Op-Ed: For better schools, abolish the politicized Department of Education and give local districts more control

- Share via

Republicans opposed the Department of Education from its beginning and regularly threaten to abolish it now, arguing that educational policy should be reserved to the states. Two respected Democrats also objected to the department’s creation almost 40 years ago. New York Sen. Daniel Moynihan warned that it would become a partisan sword. New York Rep. Shirley Chisholm worried about divorcing education from other policy areas vital to student success, such as making sure they had decent housing and enough to eat.

History has proved the critics right. It’s time for the department to be dismantled. It has done some good, especially in pointing out education inequity. But more often it has served political, not educational, interests.

In fact, the Department of Education was created by President Carter in part as a gift to the National Education Assn., for the union’s early support of his candidacy. Politics was the department’s original sin, and that reality has gotten only worse.

Although President Reagan opposed the department’s existence, he recognized its political utility. His secretary of Education, William J. Bennett, used the influence of the office as a weapon in the culture wars by promoting “traditional” curriculums. Betsy DeVos, President-elect Trump’s choice for secretary, is likely to continue its politicization. She has a track record of advancing school vouchers and charter schools. It seems probable that she will advocate for a privatization agenda, no matter the views of local communities.

School boards in towns and cities are less ideological and more pragmatic than politicians in Washington.

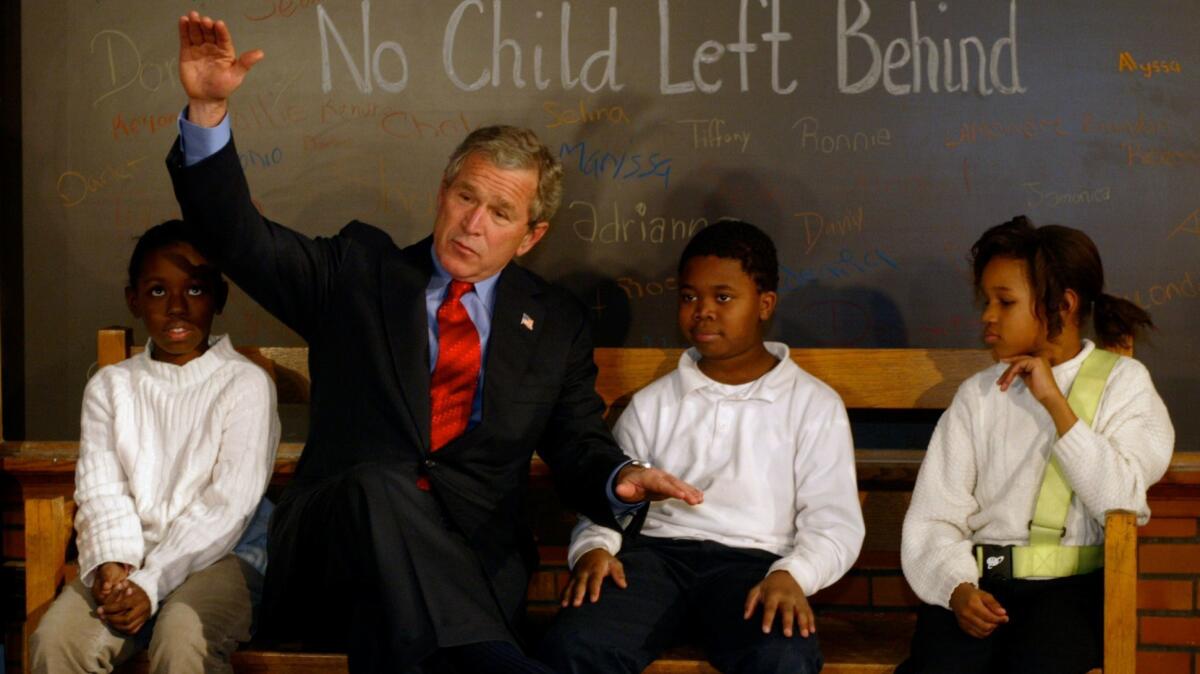

This politicization of education is most clearly evident in the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act and the department’s enforcement of its provisions. This measure — a signature part of President George W. Bush’s legacy, with an assist from Sen. Edward Kennedy — required the restructuring and potentially the closing of an entire school if all its students in specific subgroups (for example, minority, economically disadvantaged, or special ed students) did not achieve proficiency on reading and math tests. It rejected the idea that poverty, students’ home lives or other factors outside the schoolhouse might contribute to low achievement. Such suggestions were just “excuses” for bad teaching.

Of course, effective teachers, good reading and math skills, and periodic student assessments are important. But the No Child Left Behind Act had obvious failings. Universal proficiency was simply an impossible, utopian mandate. And it was a fiction that students’ life circumstances had no effect on their learning.

Rather than admit the impossibility of proficiency for all students, the Education Department took a hard line. Secretary Rod Paige declared that his “oath of office” required him to “enforce the law.” A few months after No Child Left Behind passed, he named 8,600 schools that failed to meet the law’s requirements. Unless they improved, the department would sanction them. In the face of these threats, districts slashed budgets in nontested subjects, like art and music, and students sat for exam after exam in math and reading.

The department’s approach changed only marginally under President Obama. Initially, Obama’s secretary, Arne Duncan, continued the department’s relentless enforcement of the law’s punitive provisions. But as local educators’ complaints intensified and student achievement stalled, Duncan finally admitted in 2011 — 10 years after its passage — that No Child Left Behind was a “slow motion train-wreck” and granted waivers to states to avoid the law’s full force. However, policies such as the incentive grants in the Race to the Top program still emphasized education outcomes measured by tests, the pillar of NCLB. When Congress reauthorized No Child Left Behind in 2015, the law was renamed but the focus remained on testing.

To be fair, the Department of Education didn’t initiate or write the legislation. But it did bring the full weight of the federal government against states and local school boards. No Child Left Behind erroneously presumed that Congress and the department — not local education agencies — understood how best to address schooling for high-needs learners. It’s the locals, however, who have real advantages in helping such students.

School boards in towns and cities are less ideological and more pragmatic than politicians in Washington. They see students in personal and concrete terms. They have to work with classroom teachers, local administrators and community leaders as partners. Because they are less wedded to a political dogma, they respond more quickly when a policy isn’t working for kids.

Washington has a role to play in education. The federal government alone is positioned to prevent “local control” from becoming a pretext for discrimination. It also must maintain funding to schools and colleges. But a separate executive branch department isn’t necessary to those functions. The essential tasks can be shifted to Health and Human Services and the Justice Department.

After 40 years of top-down, politically tinged intrusion, it’s possible to imagine a more collaborative, less rigid relationship between our schools and the national government. Abolishing the Education Department is a good place to start.

Bruce Meredith is former general counsel to the NEA-affiliated Wisconsin Education Assn. Council. Mark Paige, an assistant professor of public policy at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, specializes in law and education.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.