Op-Ed: Near Ferguson, a struggle that begins before kindergarten

- Share via

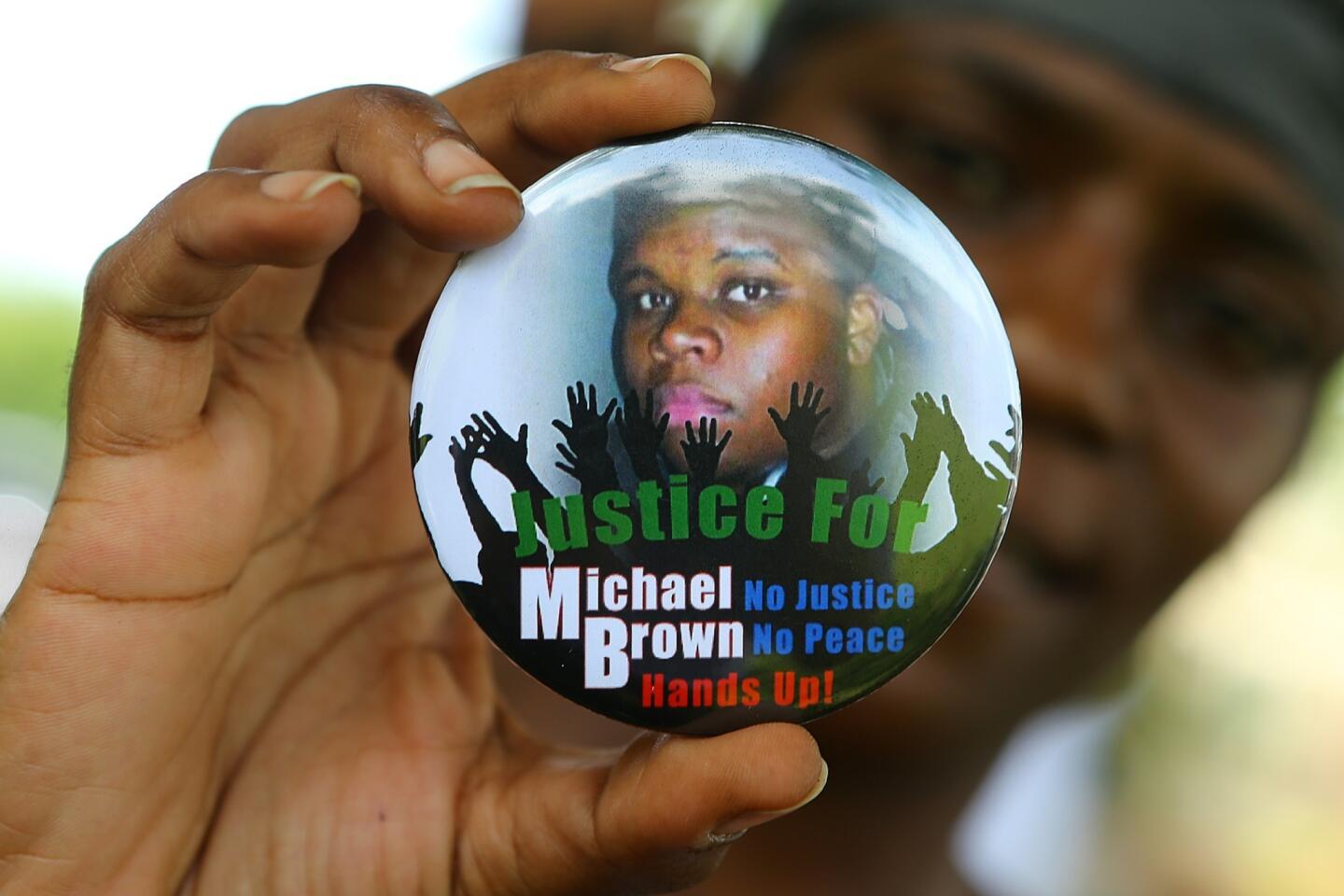

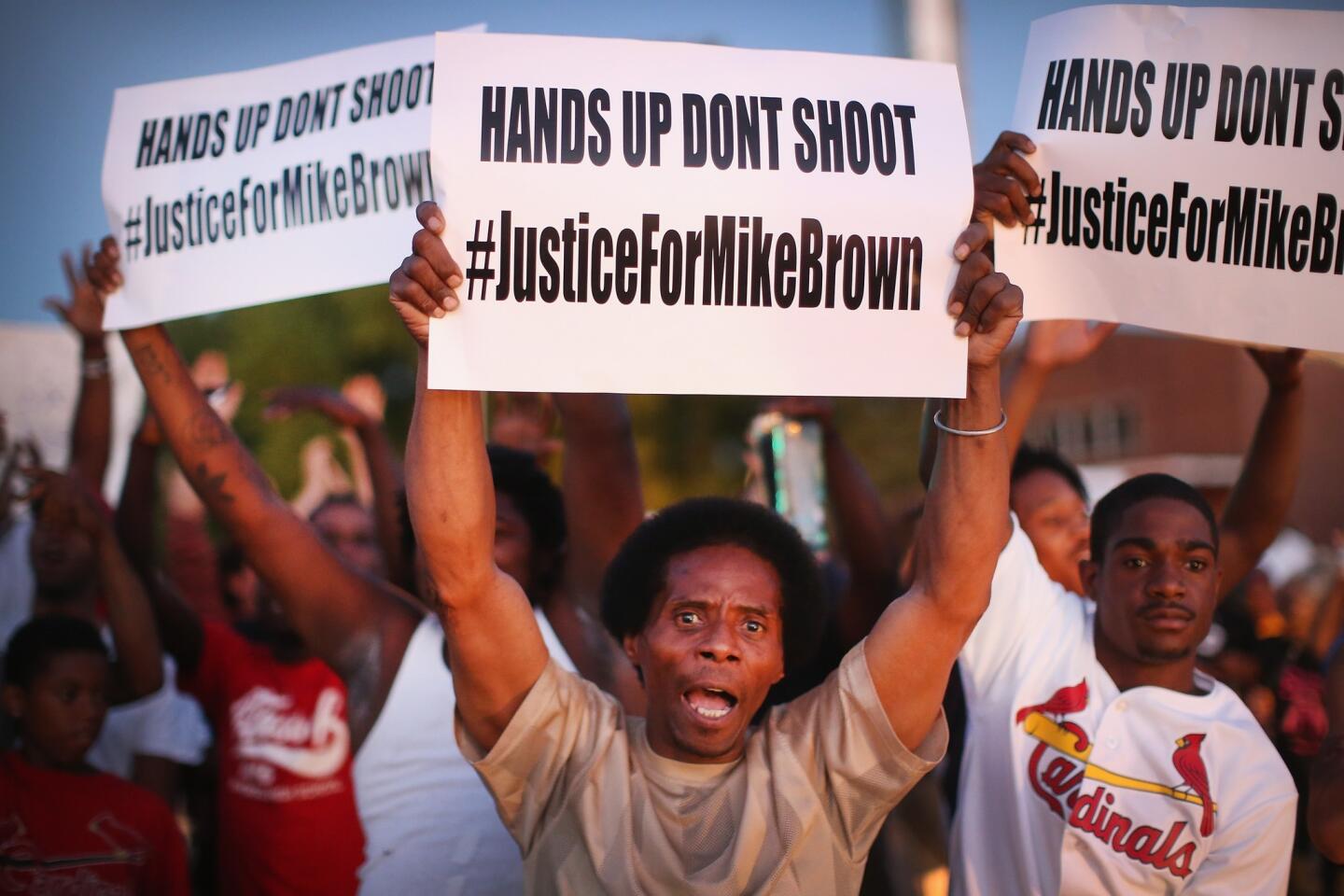

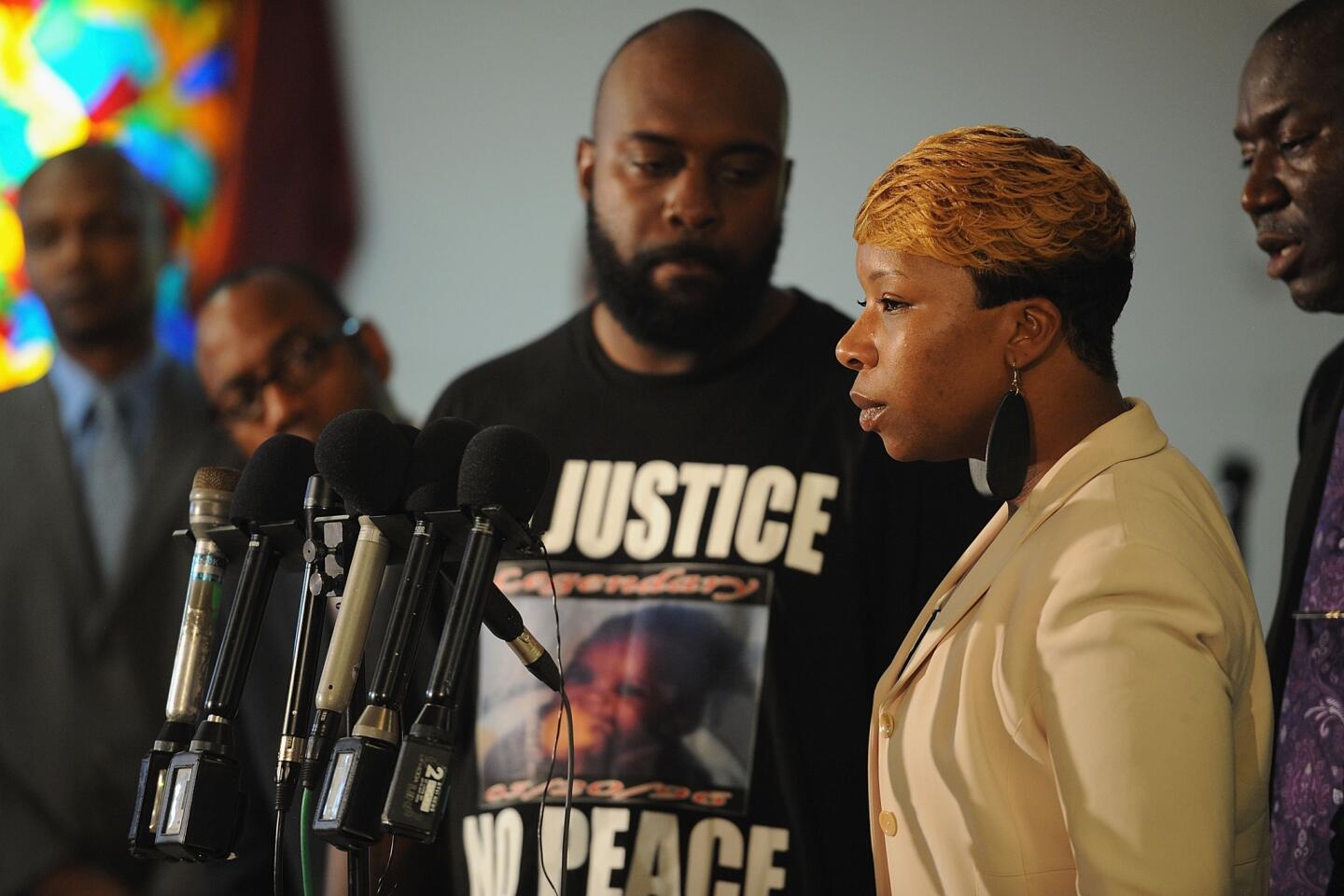

While the nation was focused on Ferguson, Mo., this summer, my attention was on a St. Louis kindergarten classroom not far from where Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white police officer. Within weeks of her East Coast college graduation, my daughter, Casey, made an unexpected detour, moving to St. Louis with Teach for America instead of returning home to California. She liked the idea of a city where she could actually afford to live independently on a teacher’s salary, she explained. And the program was having a hard time attracting black corps members to St. Louis, which has a predominantly black school district.

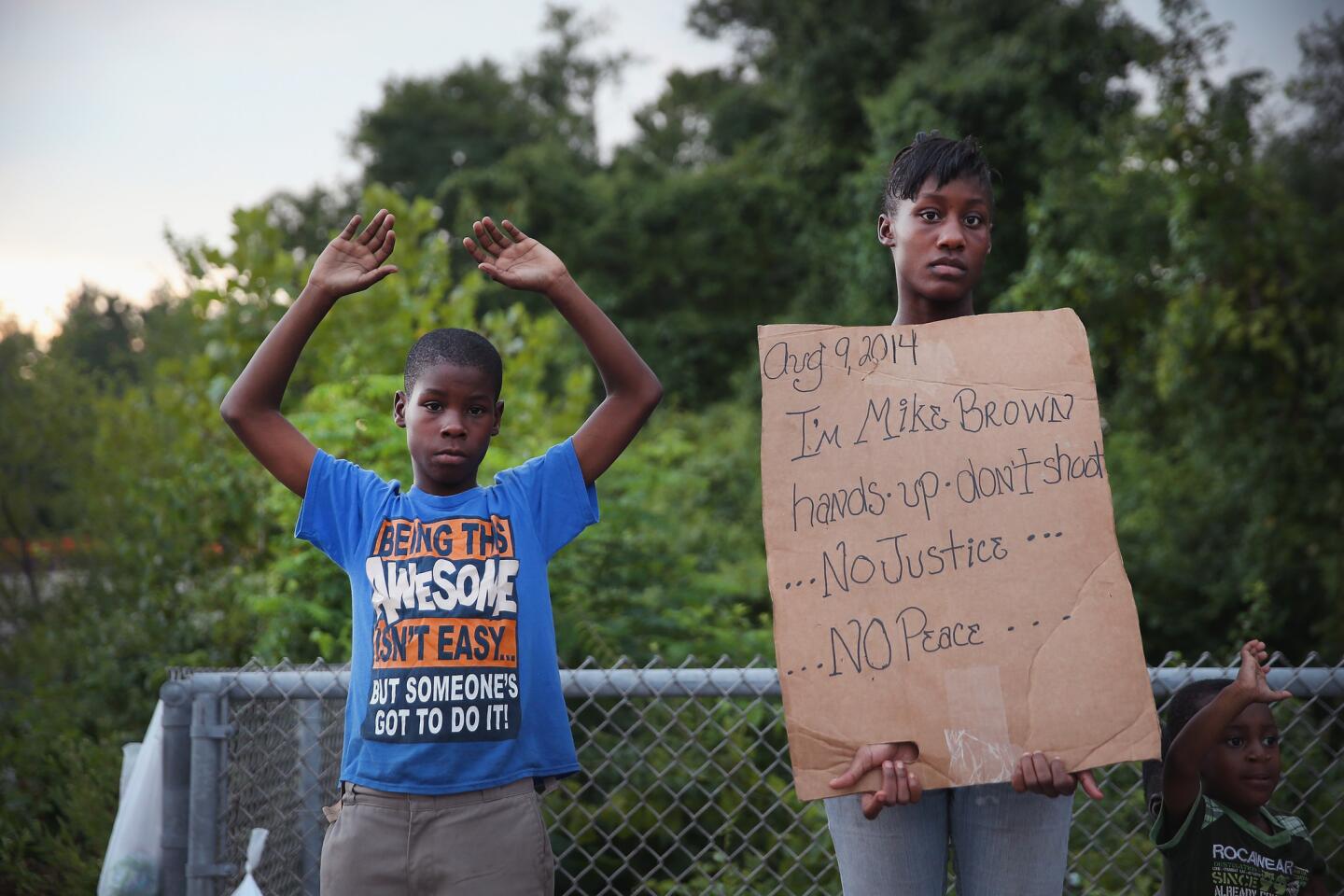

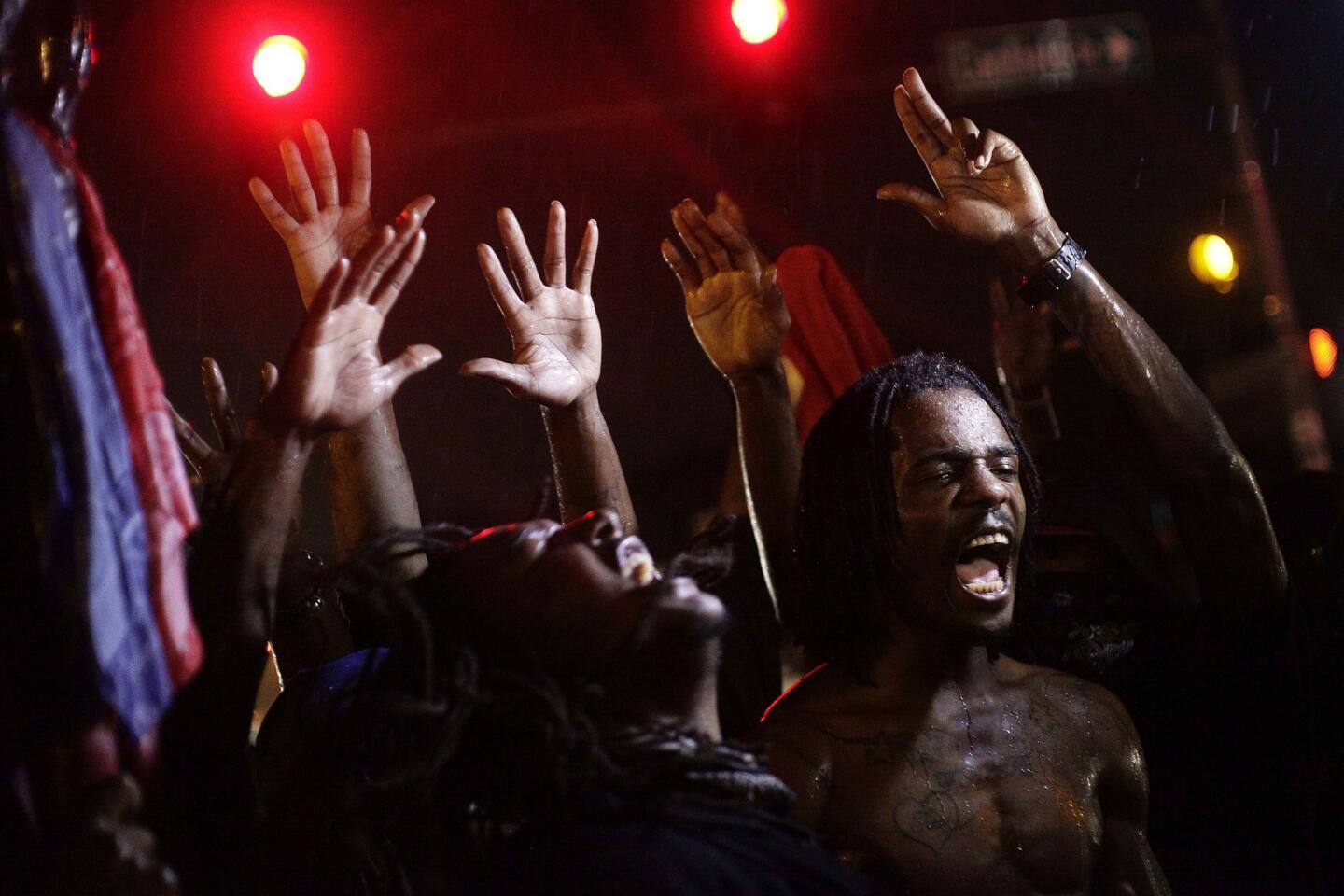

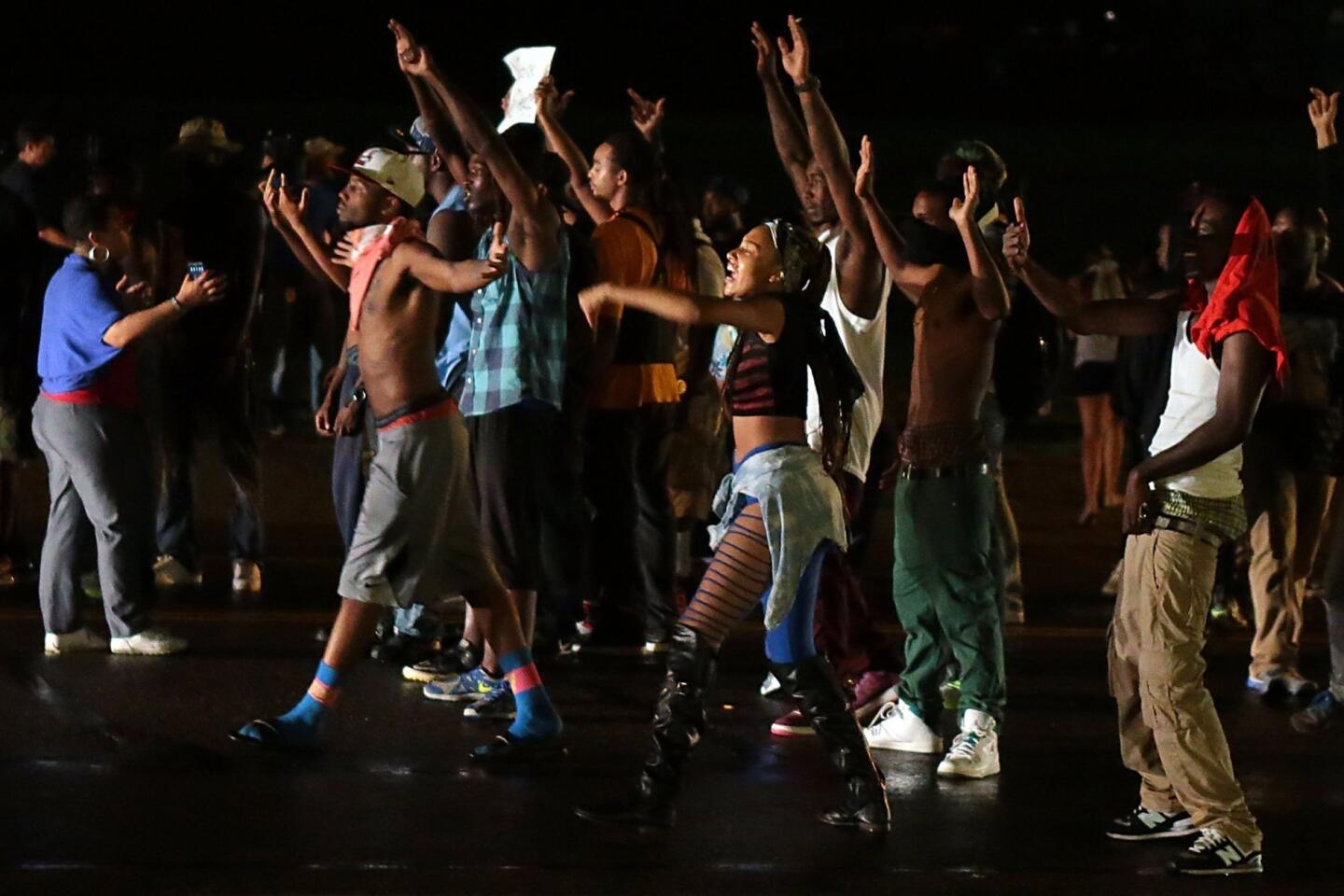

As angry protesters flowed into the streets of Ferguson, Casey coped with an overflowing classroom as a kindergarten teacher in one of the worst-performing schools in Missouri, a school at which a third of the students are classified as homeless. During the first few days of school, with little warning, additional students would appear at her door, pushing her class size past the 30-student mark. With no classroom aide and limited supplies, she struggled to find chairs, maintain order and provide guidance to a group of untamed 5-year-olds, most of whom had not attended preschool.

During her first exhausting days in the classroom, I could hear her frustration and anger over the phone.

“Mom, I have all these lesson plans and no time to really teach. My big accomplishment today was to get them to and from the bathroom.”

Falling quickly into mother mode, I offered unsolicited tips and even offered to fly in for moral support. But Casey made it clear what she needed and what she didn’t.

“Mom, I really don’t need advice right now. Just listen.”

So I listened. I listened to her tales of woe and her funny stories. When she asked one little boy to pronounce his multi-syllable name, she told me, he shrugged and said: “I don’t know. They just call me Boo.”

I wondered where most of the parents worked, and she told me they tend to work minimum-wage jobs, and many are wearing fast-food uniforms when they arrive to pick up their kids.

Casey quickly figured out that schools are not closed systems. When a family is dysfunctional or broken, the problems follow the student into the classroom. Her principal waited with a student for hours to be picked up by a parent who never appeared. Finally, at 8:30 p.m., the principal had to turn the child over to child protective services.

Still, Casey has been impressed at how, with limited resources and parenting skills, and brutal work schedules, the parents try their best to provide for their children. She also sees a large number of involved, caring fathers countering the stereotype of the absent black male.

But the families and the school struggle to make everything work in one of the city’s most crime-ridden neighborhoods. Shortly after school started, there was a drive-by shooting at a convenience store directly across the street from the school. Classes had just been dismissed, and several of Casey’s students were in the store as bullets flew, though none was wounded.

Casey’s text messages are discordant. One day she sends cute pictures of her kids in Halloween costumes; the next she alerts me that the school is on lockdown because of nearby gunfire. Recently, after yet another shooting, her principal canceled all outdoor recess. And now, in anticipation of a violent response to the upcoming Ferguson grand jury announcement, emergency supplies have been delivered to the school in case it becomes too dangerous for students or teachers to leave the building for a day or so.

But I’m trying hard to stay calm and take my guidance from Casey. She says she’s not scared — just angry that her kids have to live under these conditions. She intends to stay at least until the end of her two-year commitment. And after that? She’s already thinking about what more she can do: “I thought by teaching kindergarten, it would be early enough to make a difference, but … we’ve got to intervene earlier, focus in on parenting.”

Six weeks into the school year, I treated Casey to a weekend in New York. By then her class size was down to a more manageable 19. She was different. More confident. More serious. And angrier than ever at the injustice she sees every day playing out in her classroom.

It was hard to believe that this animated, confident young woman was the same 5-year-old I once had to hug and soothe with a cup of hot chocolate after her older brother threw her stuffed Barney out the window. Parenting seemed so much simpler then.

As we wandered through Times Square, she shared one more story that gave me pause … and hope.

“I’ve been working hard to connect with a student who is shy and withdrawn,” she said. One day, she asked him what job he thought he’d have as a grown-up.

He thought for a moment and said, “I guess I have to be president of the United States.”

“Why do you think you have to be president?” Casey asked.

“Isn’t that what all black boys do when we grow up?”

Most of Casey’s students were born in 2009 and never knew an America without a black president. For them it is normal. And that is at least one sign of progress amid the despair and anger.

Judy Belk is president and chief executive of the California Wellness Foundation.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.