Column: Internet expert Douglas Thomas on the hacking of Sony Pictures

- Share via

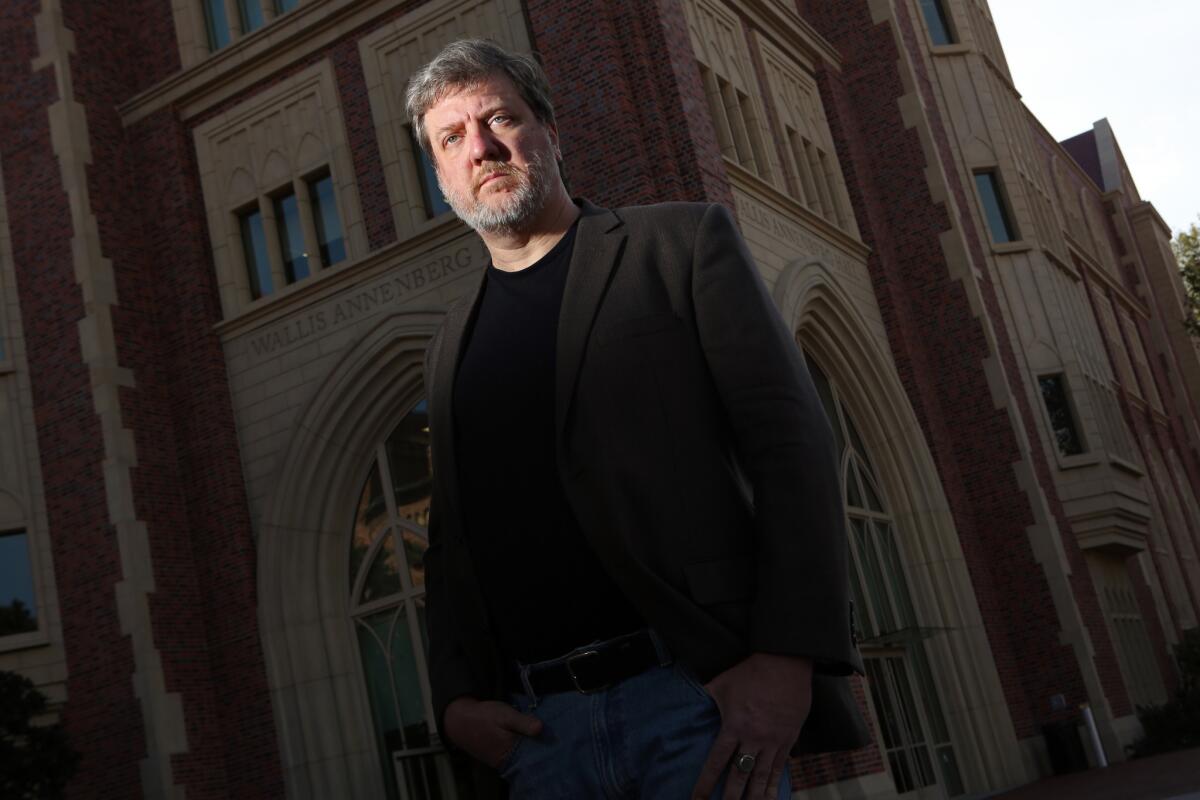

There are myriad ramifications to the hacking of Sony’s computers and the domino effect of its yanking “The Interview,” in the wake of a murky threat from the North Korean cyber underground. Putting it in perspective is Douglas Thomas’ turf. The USC associate communications professor has testified in Congress about cybercrime and security, and a lot of what he detailed in his book “Hacker Culture” is now playing out on the world stage. He sees it shaping law, politics and, yes, Hollywood — unsettlingly —- for decades to come.

The president has talked about a proportional response. In the cyberworld, what is a proportional response?

I don’t really know. Do we get our best teenagers together and have them hack North Korea?

“The Interview” got shelved, though it might surface. A Steve Carell movie set in North Korea got canceled, along with new screenings of the 10-year-old “Team America: World Police” with Kim Jong Il as a singing marionette.

Think about parallels to McCarthyism, and the way that became a culture of self-censorship. Hollywood doesn’t have a great track record of taking care of its own politically charged situations.

Setting aside the threat of cyberterrorism, can’t companies just build higher cyberwalls?

I’ve always advocated separating the terms “cyber” and “terrorism.” There was no “cyber” threat to the physical well-being of people. The hackers weren’t saying, “We’re going to shut off hospital computers and let people die in their beds.” They were saying, “We’re going to attack people with things like bombs in theaters, in physical spaces.” That is unrelated to what you can do with Sony servers. You can embarrass Sony; you can probably cause economic damage online.

So until the threat was made, this was a pretty run-of-the-mill hack?

Probably, in terms of the technical things that went on. It was more extreme because of the nature and volume of information.

The response has implications far beyond an online crime against an entertainment company.

It’s a game-changer. We’re back to the question of “Do you negotiate with terrorists?” and in a way, that’s what Hollywood has done. They’ve capitulated to these demands. “The Interview” is a comedy; it’s not a particularly important political statement, it’s not a particularly important artistic statement. This isn’t Salman Rushdie under fatwa. This isn’t Danish pictures of Mohammed. It doesn’t have the political gravitas those did.

One thing totalitarian states don’t handle very well is comedy. Mel Brooks made this point quite brilliantly about “The Producers.” He said “Springtime for Hitler” was about making Hitler into a comic figure. You can denounce him all you want, but until people are genuinely laughing at him, you haven’t won.

There have been protests over movies since movies began, but not this kind of threat of violence.

And the 9/11 trope has been a cultural warrant to make really bad decisions about things like privacy and security and fundamental human rights. That we would submit to anything in the name of fear is terrifying. This is the equivalent of saying to [Al Qaeda], “You’re right, we’re shutting down the New York Stock Exchange.” It’s like giving the bully your lunch money every day. Everybody knows that never makes things better.

Either there’ll be big repercussions because Hollywood will follow suit, or people won’t follow suit and Sony will end up looking cowardly and in a sense unpatriotic.

How hard is it to make laws against virtual crime?

It’s enormously difficult, in part because we’re always building off laws that were intended for something else. You get laws which don’t [work]. How do you talk about trespass — for example — in a virtual world? Trespass is predicated on the idea that your body is someplace it shouldn’t be. But when you’re on your computer in your mom’s basement, that’s no longer true. You’re looking at things you shouldn’t be looking at. It’s not a crime to walk up to someone’s car and look in the window and admire their stereo. It’s only a crime when you open the door and pull that stereo out.

Is that all that most hacking is, looking in the car window?

A lot of hackers do that. They just want to get in for the simple reason that they’re not allowed to. They want to hack as a challenge: Can I break into Sony, look at the script for the next James Bond movie? Maybe they would post part of it as a trophy; that’s where they start getting into trouble and they’re pretty aware of that. It’s also structured around boy culture, flouting authority. It used to about spray-painting the overpass. Now it’s about defacing a Web page.

You expect laws drafted in the wake of the Sony hack to be ineffective or worse?

Exactly. There will be some grandiosely named bill introduced under the cover of protecting American films from hacking and terrorism, and my guess is that the MPAA (the Motion Picture Assn. of America, the studios’ Washington lobbyist) will slide in language about piracy and try to backdoor much more restrictive laws about intellectual property. That is the danger — the stuff that gets backloaded into legislation, taking advantage of a moment when we really do need better laws.

Sony’s bottom line may be most affected by the piracy related to the hack. In 1982, MPAA chief Jack Valenti told Congress “The VCR is to the American film producer ... as the Boston Strangler is to the woman home alone.” Is piracy just about the Internet’s “free’’ ethos?

That’s a big part of it. [In 1976] Microsoft put out a copy of the Altair BASIC computer program, which was immediately ripped off by everybody, and Bill Gates wrote an angry “Open Letter to Hobbyists” that asked, “Why is it you believe hardware is something you pay for and software is something that should be free?” That dichotomy has persisted. There are all kinds of justifications; it’s hard to make the argument Valenti made with a straight face.

I can’t imagine Joss Whedon saying, “I’m not going to direct the next ‘Avengers’ because there’s no money in it.” When a film grosses $1.5 billion, it’s hard to get traction with the argument that piracy is killing us. The rhetoric doesn’t line up with reality as people see it; we don’t see the music business falling apart, we don’t see films no longer coming out. That may be happening, but it’s not visible to the average person.

Then there’s attorney David Boies’ claiming the leaked Sony emails are stolen property and whoever publishes them could face legal action.

He’s right that you become complicit the minute you look. I also know when I’m driving down the freeway and there’s an accident, I really shouldn’t look, yet it doesn’t always work out that way.

When we talk about the theft of music online — if you push people hard enough, they’ll agree that downloading an MP3 is stealing. But they see their impact as minimal. You see the same response from people who say, “I know I shouldn’t look but it’s out there, it’s interesting.”

You want the press to behave responsibly and you kind of have to leave it up to the press to know what that looks like. Once you have regulations, it’s no longer a free press. We’re stuck with a system that’s not ideal. [But] Jennifer Lawrence suing the New York Times for publishing a [stolen] picture of her naked would be a big deal.

It would be a big deal if the New York Times published a picture of just about anybody naked!

But [some websites] would say bring it on, it will just bring more people to my site and you’re never going to win.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Twitter: @pattmlatimes

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.