Dodger great Carl Erskine: Pitching equality

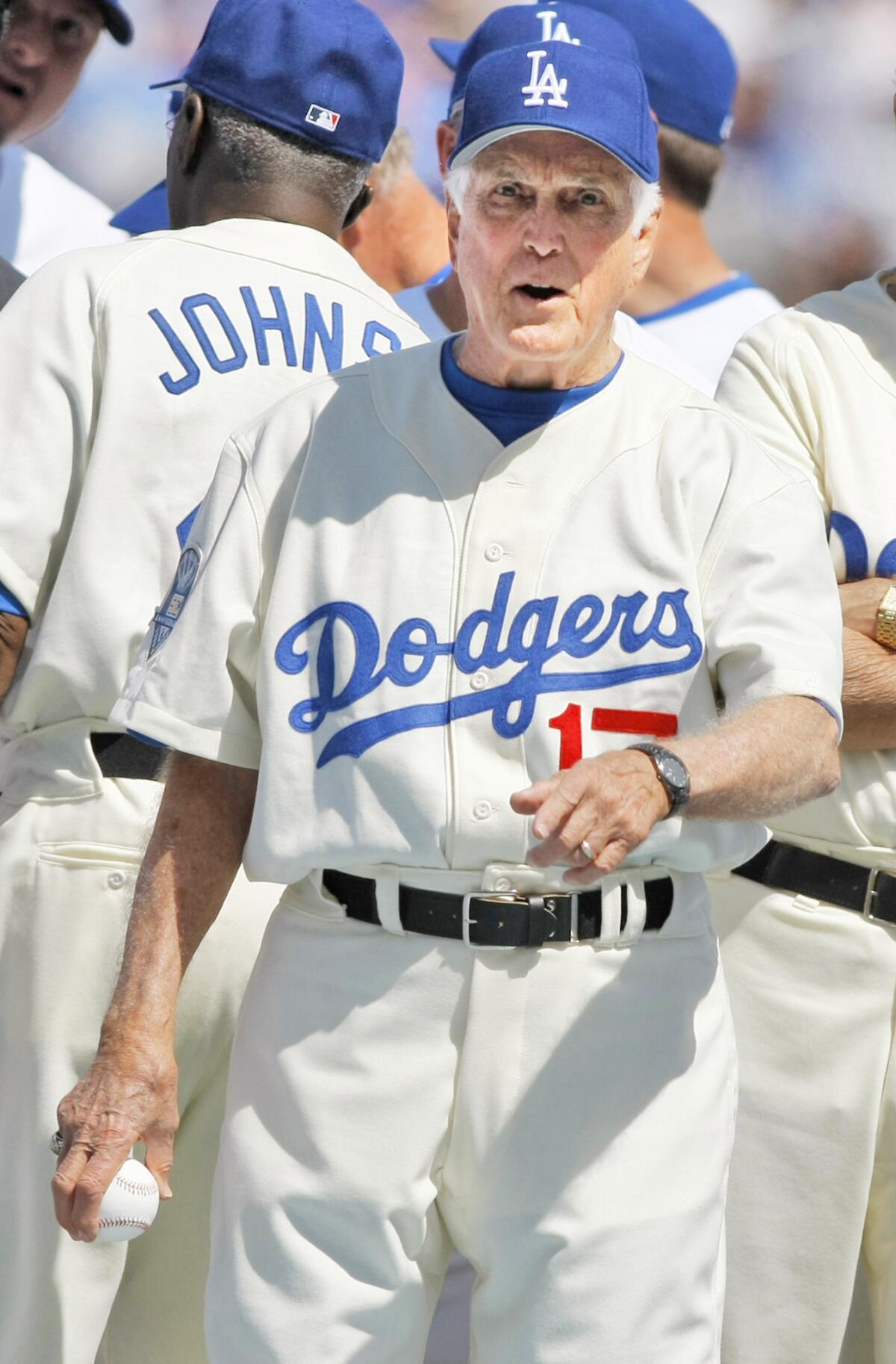

Former Dodger great Carl Erskine threw out the first pitch in 2008.

- Share via

Jackie Robinson changed baseball and the nation that loves it on April 15, 1947, when he became the first black player to walk onto a major league ball field. He changed Carl Erskine’s life in March 1948, when Robinson, by then a Brooklyn Dodgers star, sought out the minor leaguer after watching him pitch and told him, “You’re going to be with us real soon!” And so he was — they were teammates through much of he Dodgers’ legendary 1950s. The Robinson biopic “42” is mostly about matters that happened before they met, but Erskine knows what happened afterward: He pitched and won the first Dodger game in L.A., retired in 1959 to his hometown in Indiana, and watched the nation gradually understand the life lessons he later wrote about in “What I Learned from Jackie Robinson.”

When Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, you were on a farm team. Was it a big topic for players that day?

There wasn’t much about it. Amazing. [New York sportswriter] Leonard Koppett said the account in the New York papers the day Jackie played his first game was a very small paragraph. That day came and went. Jackie continued to make his mark, brought new energy to the game, packing ballparks wherever we played.

But it wasn’t smooth sailing, especially in the South.

In Atlanta, he got a threatening letter: “Don’t take the field, you’ll be shot.” Not only did the [Ku Klux] Klan show up, but a black fan couldn’t buy a ticket, so the levee behind the right-field fence was covered with black fans to see Jackie. We played the game and went on.

I went through Atlanta the other day and lo and behold, at the ballpark, there’s a statue of Henry Aaron, in the setting that wouldn’t sell a black fan a ticket in 1949. That’s a major leap forward.

There was resistance even in the Dodgers clubhouse.

There was a flurry at the beginning. Dixie Walker and Bobby Bragan, both from Alabama, said, “We don’t play with him,” and asked to be traded. It’s natural they would oppose it in the beginning; imagine them going home and [locals] saying, “You shower and eat with this guy? You go to the same hotel?” After Bragan and Walker got to know Jackie, they changed their position and were very supportive.

The beautiful part is America has become more embracing of people who are different.

Jackie was filled with his passion to break this thing. He also knew he didn’t have a lot of time in his baseball lifetime. Jackie saw a lot of changes, but he died before he saw all these — I mean, a president of color? A black part-owner in Los Angeles?

You believe baseball changed fast, that it took America longer to come around.

It’s a contrast nobody makes a whole lot of. Baseball accepted Jackie quickly. Contrast that to society, which wouldn’t let Jackie stay in the same hotel with us. In uniform, he was a standout. In civvies, he was just another black man in America.

Robinson knew you didn’t have a problem with him?

Indiana had a reputation of being sympathetic with the Klan. A community down the road, Elwood, had a sign, “N-word, don’t let the sun set on your head in this town.” [But] I grew up in a mixed neighborhood. My best buddy was [future Harlem Globetrotter] Johnny Wilson. He’s still my good buddy. Jackie said: “You don’t have any problem with this race business, do you?” I told him what I just told you. It was a no-brainer.

You revere Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ president and general manager, who chose Robinson not just to play baseball but to integrate it.

Mr. Rickey was the wisest man I’ve ever known. He challenged Jackie for the big picture: Not baseball — that was the vehicle. Mr. Rickey called bigotry “the bully,” and he said when you face the bully, he wants you to run or fight back. When you won’t do either, when you look at him with compassion and even take a second blow, he’s defeated. He’s done.

They both were raised by strong Christian mothers. Jackie could identify with this parable of passive resistance. That, and his wife, Rachel, such a class person, and Jackie’s own intelligence in seeing that what he was doing was far more than being a good ballplayer, was a tipping point [for Rickey].

Who [else] would have stepped forward the way Mr. Rickey did? Once Jackie was on the field, nobody could help him. He had to catch the ball, hit the ball, and the New York sportswriters voted Jackie rookie of the year in his first year.

Rickey put a three-year gag order on Robinson, not to talk about civil rights.

He wasn’t to make any response [to racism], but after two years, he handled it so well that Mr. Rickey forgave the third year. Then it just gushed out of Jackie. He had a syndicated column, became a strong advocate for civil rights and how much was not getting done. Black leadership then and now do not support Jackie for the civil rights impact he really had. You hear [them] start with Martin Luther King Jr. when you talk about civil rights. I think it should start with Jackie.

You saw Robinson confront a drunk black fan at a double-header in Cincinnati.

That was the maddest I ever saw Jackie. We were getting ready for the second game when this fan, drunk and half disheveled, came toward the dugout saying, “I want to see my boy Jackie.” Jackie was enraged: “Get out of my sight, go home.” He was embarrassed. What he was trying to do on the field, to dignify his whole race, and this was a total insult to Jackie.

He was no plaster saint though.

Baseball is hard-nosed. Baseball was chock-full of rough talk, and Jackie was able to give it back big-time. He was no shrinking violet. There were some exchanges between Jackie and [ex-Dodger and then-New York Giants Manager] Leo Durocher that were classic — imagine that profanity had an eloquent component. Yet if they met on the street, it was altogether different.

Did he hear the N-word from players?

Yes. If there was anything in your background that could be used to upset you — if you walked funny or whatever. Not every player was that way. Jackie heard plenty, and after the gag order, Jackie got very verbal.

Robinson, who grew up in Pasadena, didn’t come to L.A. with the Dodgers.

Mr. Rickey was identified 100% with Jackie. Walter O’Malley bought Rickey out, and there was a bitter parting. Mr. O’Malley began to get rid of people who were identified as Rickey people, and certainly Jackie was a Rickey person. So Mr. O’Malley did what most owners would want to do. He had a new franchise on the West Coast and did not want to be identified as a Brooklyn Dodger carryover.

Brooklyn Dodger players were never invited to an old-timers’ game in Los Angeles. Jackie was invited by the Angels [in 1969], and when he got to the mike he ripped Mr. O’Malley and the Dodgers for not having had the guts to invite him back, [that] it took an American League team to invite him to Los Angeles.

Now, Mr. Peter O’Malley, he knew all of us as players when he was a teenager. He and his sister Terry made a significant effort to reconnect the history, and that’s the way it is today.

Do players today know who Robinson is?

One of my teammates, pitcher Joe Black, came in after Jackie and praised him to the high heavens for getting the door open so he and other black players could have a shot. Joe Black went to his grave a few years ago brokenhearted that when he talked to black major league players and mentioned Jackie, he’d get a response, “Jackie who?” It just broke his heart. But now baseball has begun to put the history of Jackie’s impact [back] in the game.

You think Robinson helped smooth the path for your son, Jimmy, who has Down’s syndrome. You wrote a book about it.

Jackie’s impact started a momentum [for] Americans to see things differently. The parallel of my [playing] with Jackie and then watching all these indignities [Jimmy experienced]: When Jimmy wins a medal in the Special Olympics, I say Jackie had something to do with that. It’s quite remarkable.

You joke about living a bland life, but you’ve won the World Series, pitched two no-hitters and befriended Jackie Robinson.

I’ve had one hometown, played for one team, had one wife, hit one home run. Nothing fancy!

Follow Patt Morrison on Twitter @pattmlatimes

This interview was edited and excerpted from a taped transcript. An archive of Morrison’s interviews can be found at latimes.com/pattasks.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.