Editorial: Why is the White House having such difficulty gathering data on police violence?

In 1930, the public believed that crime was climbing dramatically around the country. But was it? No one knew for sure. So the federal government began collecting crime data from local law enforcement agencies. In the end, it took decades to persuade all the police departments in the nation to provide information in a uniform way.

Today, the process is easier, with computers and the Internet to help. So it is disappointing that the first year of the White Houseâs Police Data Initiative has produced so few solid results. Only 53 police departments â out of about 18,000 nationwide â have agreed to share data beyond the typical crime statistics already collected by the FBI. The bureau is looking to include use of force incidents, traffic stops and citations issued, among other things.

Twelve of the 53 departments committed to the police data project are in California, including those in the stateâs four largest cities and in its largest county.

As of now, it is up to the departments themselves to decide what information to share. And how to share it. Because departments donât necessarily use the same language or metrics to describe incidents, data sets that look similar might in fact be wildly divergent. What one police department considers a âuse of force,â for example, may be an unremarkable handcuffing at another department.

This is a problem because without common standards and definitions, and without reliable data, it will remain impossible answer the basic questions that precipitated White House initiative: Are police too quick to arrest, harm, shoot and kill unarmed African-American men?

The police data project was recommended by a task force created by President Obama in 2014 to address of high-profile officer-involved shootings from Ferguson, Mo. to Los Angeles The concept was to establish a virtual platform where the nationâs police departments would share data so that it could be studied and compared by researchers, mined by commercial data scientists, plugged into apps by tech companies and viewed by anyone interested in how police interact with the public.

This is just a first step of an enormous undertaking, and the feds are relying on a collaborative approach since they lack the authority to force local police to participate. But the public canât wait another 50 years to get the answer to these questions. Nor is there any good reason why they should. Tools that didnât exist in 1930 now make reporting data to the government as uncomplicated as e-filing income tax returns. And those standards arenât going to set themselves. Rather than hoping standards develop organically, an approach the leaders of this initiative favor, they must develop clear standards describing exactly what data should be reported and how.

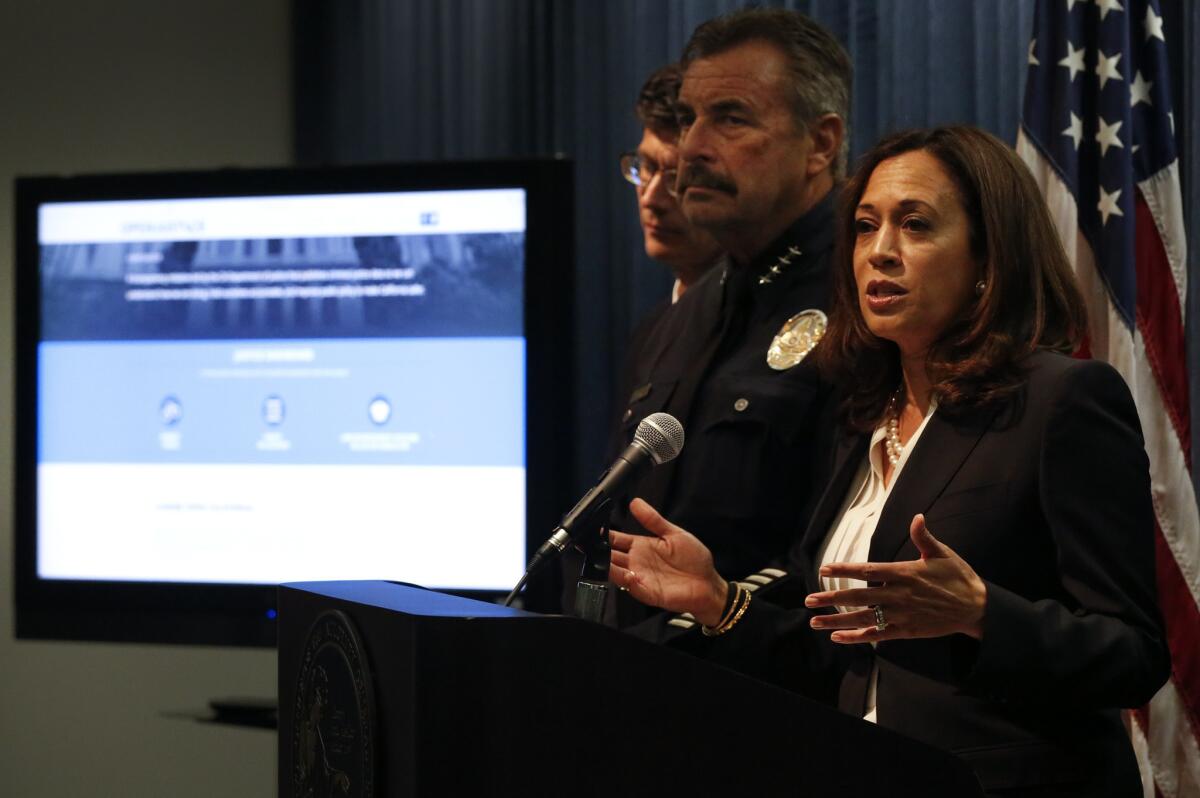

There is a silver lining to this disappointing beginning. Twelve of the 53 departments committed to the police data project are in California, including those in the stateâs four largest cities and in its largest county. Thatâs a hopeful sign for the entire effort; California has led other states in the collection and reporting of data such as the number of people killed by police each year (though it hasnât been all that forthcoming about sharing it with the public until recently). And perhaps the example of the California Attorney Generalâs office, which took less than a year to launch its data project, Open Justice will rub off on the White House.

The police data project marks its one year anniversary in May. If the project is to survive its infancy, it must do a better job in its second year by persuading more departments to participate and setting clear standards for how they do so.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.