The looted art of Europe

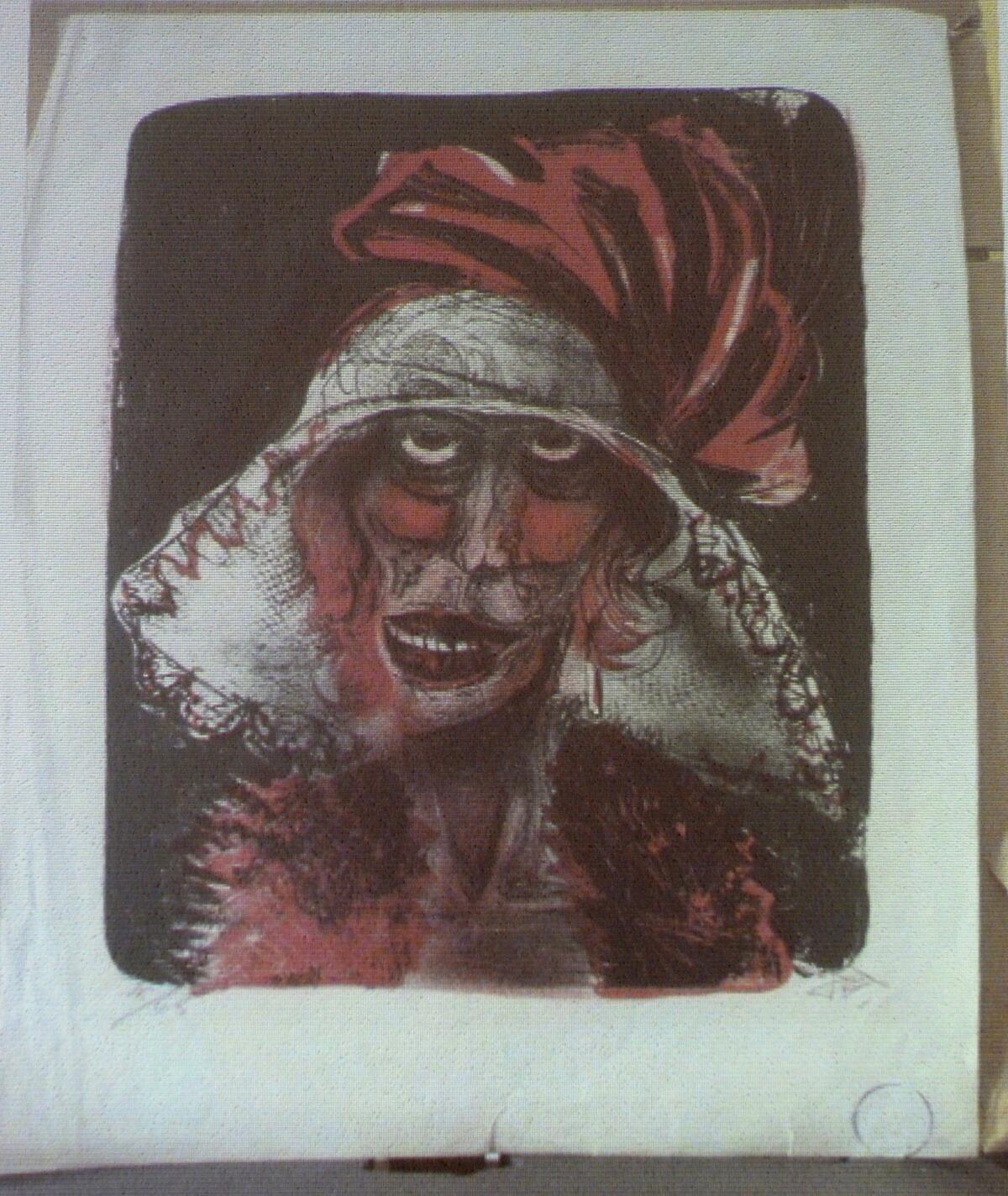

It is not terribly surprising that Adolf Hitler hated most modern art, which he saw as “degenerate” and which he believed had been contaminated by the influence of, yes, the Jews. His taste ran more to the work of Eduard von Grützner, a Munich-based painter known for his portraits of portly, smiling monks.

As chancellor of Germany, Hitler imposed his artistic taste on the public by confiscating — in effect, stealing — modern works from their owners. Even art that was not particularly modern was often taken from its owners, especially if they were Jewish, through forced sales and other means.

Artworks lost during the Nazi period reemerge from time to time, but not as dramatically as the most recent cache — some 1,400 paintings by Picasso, Chagall, Matisse, Renoir and others found in the dusty little Munich apartment of a man being investigated for tax evasion. The man, identified in news reports as 80-year-old Cornelius Gurlitt, is the son of an art dealer who sold confiscated “degenerate art” on behalf of the Nazi regime to people in other countries, thus ridding Germany of supposedly offensive works while bringing in revenue.

It is astonishing and wonderful that this enormous trove of missing European art has come to light. But it is disconcerting that even after 70 years and other discoveries of looted art, Germany is handling this situation in an unaccountably secretive manner. In 1998, Germany signed on to an international agreement that called for more openness and transparency in order to facilitate the return of confiscated works to their rightful owners.

The discovery of the Gurlitt trove didn’t even come to light until more than 18 months after it was found. The government has refused to make public a list of the works or to release more than a handful of photographs, which makes it extremely difficult for the original owners or their descendants to know whether they might have a claim.

Even under the best of circumstances, the scholars who are now poring over the artworks would face a tremendously difficult task in determining their value, provenance and proper ownership. It’s also quite possible that many of the works legitimately belong to Gurlitt, if his father bought them from people who were not put under duress to surrender them.

But given what happened in secret to so many of Europe’s great works of art before and during World War II, transparency is called for as this case unfolds. The fate of art looted during the Nazi era isn’t just an internal German matter; it’s a matter of international law, of justice for those who were persecuted in their home countries and of global interest in the reemergence of valuable art that was once called degenerate.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.