Ukraine’s threat from within

It’s become popular to dismiss Russian President Vladimir Putin as paranoid and out of touch with reality. But his denunciation of “neofascist extremists” within the movement that toppled the old Ukrainian government, and in the ranks of the new one, is worth heeding. The empowerment of extreme Ukrainian nationalists is no less a menace to the country’s future than Putin’s maneuvers in Crimea. These are odious people with a repugnant ideology.

Take the Svoboda party, which gained five key positions in the new Ukrainian government, including deputy prime minister, minister of defense and prosecutor general. Svoboda’s call to abolish the autonomy that protects Crimea’s Russian heritage, and its push for a parliamentary vote that downgraded the status of the Russian language, are flagrantly provocative to Ukraine’s millions of ethnic Russians and incredibly stupid as the first steps of a new government in a divided country.

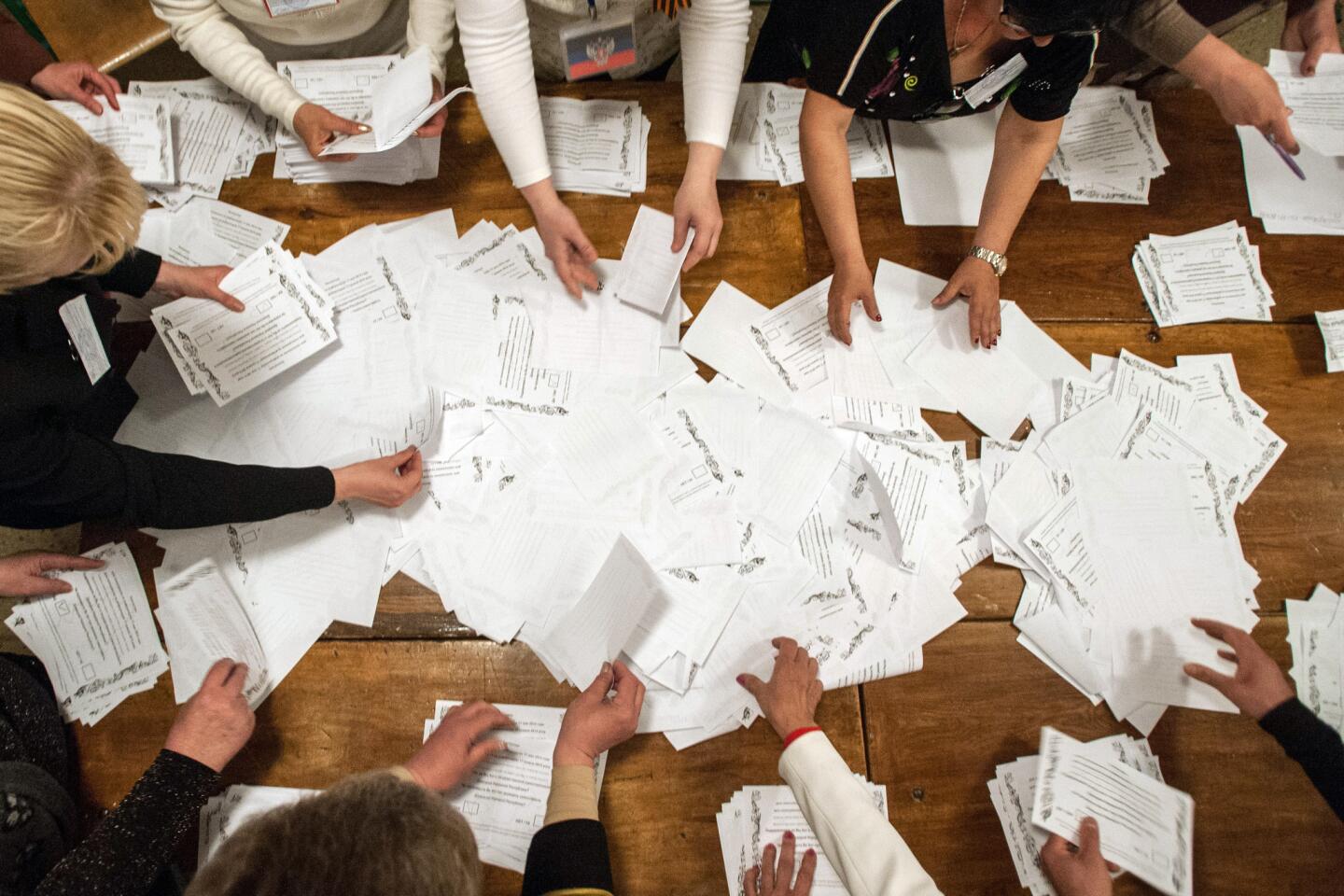

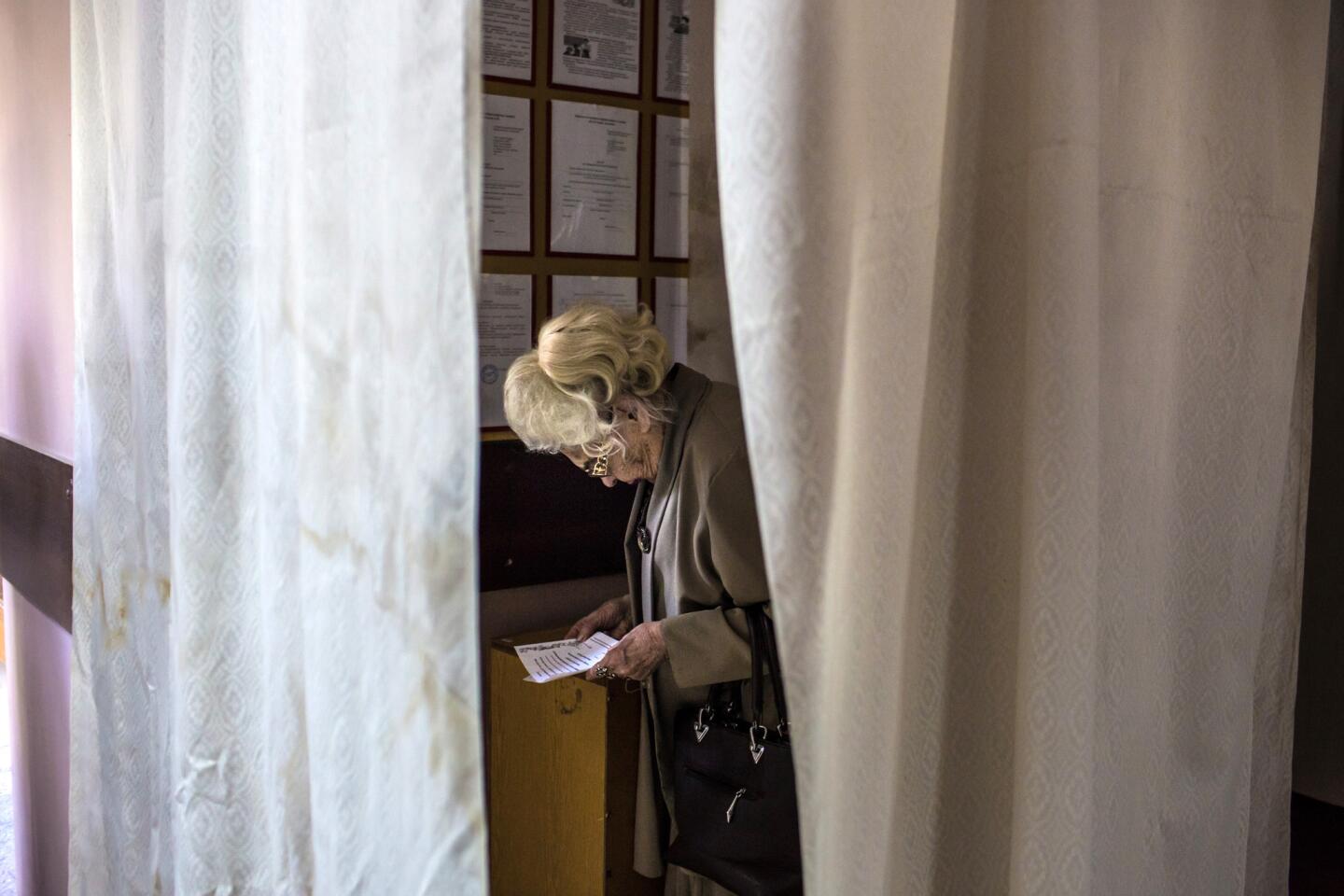

These moves, more than Russian propaganda, prompted broad Crimean unease. Recall that this crisis began when Ukraine’s then-President Viktor Yanukovich retreated on a deal toward European integration. Are the Europe-aspiring Ukrainians who now vote to restrict Russians’ cultural-language rights even dimly aware that, as part of the European Union, such minority rights would have to be expanded, not curtailed?

PHOTOS: A peek inside 5 doomed dictators’ opulent lifestyles

More to the point, why wave a red flag in front of a nervous bull? The answer is that for Svoboda, Right Sector and other Ukrainian far-right organizations, it was barely a handkerchief. These are groups whose thuggish young legions still sport a swastika-like symbol, whose leaders have publicly praised many aspects of Nazism and who venerate the World War II nationalist leader Stepan Bandera, whose troops occasionally collaborated with Hitler’s and massacred thousands of Poles and Jews.

But scarier than these parties’ whitewashing of the past are their plans for the future. They have openly advocated that no Russian language be taught in Ukrainian schools, that citizenship is only for those who pass Ukrainian language and culture exams, that only ethnic Ukrainians may adopt Ukrainian orphans and that new passports must identify their holders’ ethnicity — be it Ukrainian, Pole, Russian, Jew or other.

Is it so hard to understand Russians’ shock that senior U.S. officials (such as Sen. John McCain, Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland) flirt with extremists who have been denounced as anti-Semitic, xenophobic, even neo-Nazi by numerous human rights and anti-defamation groups? That they were snapping pictures and distributing pastries among protest leaders, some of whose minions were at that same moment distributing “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” on Independence Square?

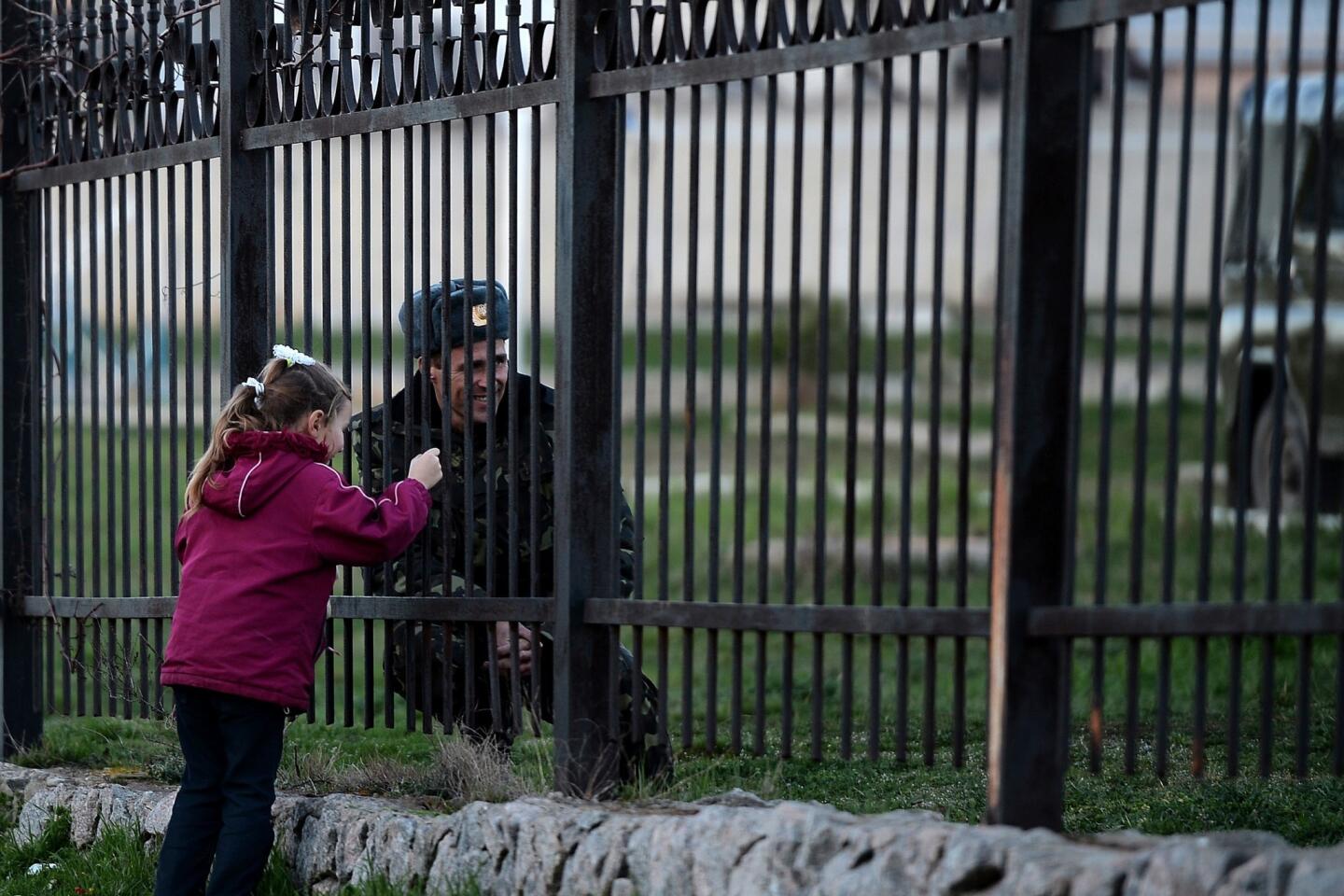

In the few instances where concern over such extremists is acknowledged, it is usually dismissed along the lines of, “Yes, the new government isn’t perfect, but moderates will soon prevail.” But Russian worry is well-founded. Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, millions of ethnic Russians or Russian speakers have endured loss of citizenship in the Baltic republics (where many lived for generations), have been driven out of Central Asian jobs and homes and have suffered particularly virulent discrimination in Georgia (the root cause of the 2008 war with Russia, but also broadly ignored in the West).

How did such extremists capture key posts in the new Ukrainian government? If Svoboda was only a minority faction in the parliament (and Right Sector just a fringe paramilitary group), and their ideology is not shared by a majority of Ukrainian moderates, then doesn’t that mean that Putin is right? That Ukraine’s cobbled-together-under-street-pressure new government is indeed unrepresentative, and therefore illegitimate?

It recalls some extreme tea-party tail wagging the Republican dog. When Ukrainian ultranationalists can intimidate moderates into backing out of an agreement that would have eased Yanukovich from office and thus saved many lives, and then in-

to supporting discriminatory moves toward Ukraine’s Russians, we can appreciate why the latter are nervous. The U.S. has hardly stood up for the Russians suffering discrimination and violence since the Soviet Union’s collapse. Now, with tacit U.S. approval of the Ukrainian extremists whose avowed goal is to ratchet up pressure on the country’s Russian minority, Putin’s warning doesn’t seem quite so paranoid.

Why wouldn’t we ease those fears by forcefully denouncing the ethno-nationalists and embracing minority rights as vital to the stable Ukrainian democracy that we seek to promote? Given our own hypocrisy — don’t violate agreements (except the one not to expand NATO eastward), don’t invade countries on phony pretexts (except Iraq) and don’t support minority secession movements (except Kosovo) — why wouldn’t we want to restore U.S. credibility by living up to our principles in this critical case?

The European Parliament in 2012 condemned Svoboda’s racism, anti-Semitism and xenophobia as “against the EU’s fundamental values and principles.” The U.S. should not hesitate to do likewise now. It is not only the right thing to do, it would also open a door to compromise with Russia over this dangerous crisis. To remain silent sends exactly the wrong message to extremists on both sides.

Robert English is director of the School of International Relations at USC.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.