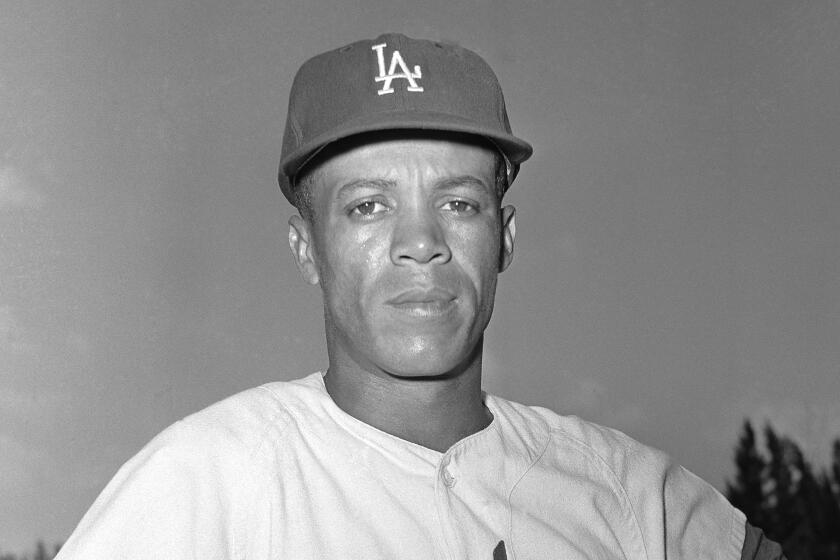

Maury Wills, legendary base stealer for Dodgers, dies at 89

- Share via

A light-hitting shortstop, Maury Wills spent nearly a decade in the minor leagues honing his limited skill set, studying the tendencies of pitchers and teaching himself to hit from either side of the plate.

When the Dodgers finally pulled him up to the big leagues, it paid off in spectacular fashion as he helped take them to three World Series titles in four tries and nearly single-handedly reintroduced base stealing as a major offensive weapon.

An integral part of the 1960s Dodgers, Wills went on to lead the National League in steals six times, earned two Gold Gloves for his fielding and beat out Willie Mays for the league’s most-valuable-player award in 1962, when he mesmerized the baseball world by setting a record with 104 stolen bases, eclipsing the 47-year-old mark of 96 by the immortal Ty Cobb.

Never far from the stadium where he did so much of his damage to opposing clubs, Wills died Monday night at his home in Sedona, Ariz., the Dodgers announced Tuesday. He was 89.

Wills became a valued instructor with the Dodgers in his later years and developed a strong relationship with a young base stealer when Dave Roberts was traded from Cleveland to the Dodgers in December 2001. Roberts stole 118 bases in 2½ seasons before being traded to the Boston Red Sox, for whom he executed maybe the most famous stolen base in history during the 2004 American League Championship Series.

Roberts, who as the Dodgers’ manager wears No. 30 as a salute to Wills, had a single tear running down his cheek as he spoke about his mentor before the first game of a doubleheader Tuesday at Dodger Stadium. Wills career highlights were shown on the stadium video boards and the Dodgers added a patch with No. 30 to their jerseys in his honor.

“He just loved the game of baseball, loved working and loved the relationship with players,” Roberts said. “We spent a lot of time together. He showed me how to appreciate my craft and what it is to be a big leaguer. He just loved to teach. So I think a lot of where I get my excitement, my passion and my love for the players is from Maury.”

Roberts said he “probably” wouldn’t be managing the Dodgers if not for Wills and his influence.

“And in a strange way, I think I enriched his post-baseball career as far as watching every game I played or managed,” Roberts said. “I remember even during games I played, he’d come down from the suite and tell me I need to bunt more, I need to do this or that. ... A coach would say, ‘Maury is at the end of the dugout and wants to talk to you.’

“It just showed that he was in it with me, and to this day, he would be there cheering for me.”

Batting leadoff, Wills hit .299 the season he set the stolen-base record, collecting 208 hits, all but 29 of them singles. At the just-opened Dodger Stadium, though, those lowly singles brought chants of “Go! Go! Go!” and Wills was happy to oblige, usually successfully.

He was caught stealing only 13 times that season and later said that number really should have been eight because five times he was thrown out when Jim Gilliam, hitting behind him, failed to connect on hit-and-run plays. His prowess on the basepaths that season resulted in a career-high 130 runs scored.

So feared was Wills that the San Francisco Giants’ grounds crew dug up the basepath and added peat moss and damp soil to slow him down in a critical late-summer game in 1962 at Candlestick Park.

Wills chuckled at the memory of the shenanigans years later in a 2021 interview with The Times’ Houston Mitchell. “I was flattered that they would go through all that trouble to try to stop me,” he said.

Dodger legend Maury Wills answers some questions posed by newsletter readers.

Wills stole 586 bases in his 14-year career and, in his retirement, told the Centre Daily Times of State College, Pa.: “When you’re a base stealer, you’re a different cut of guy. ... You’ve got to be arrogant to be a good base stealer.”

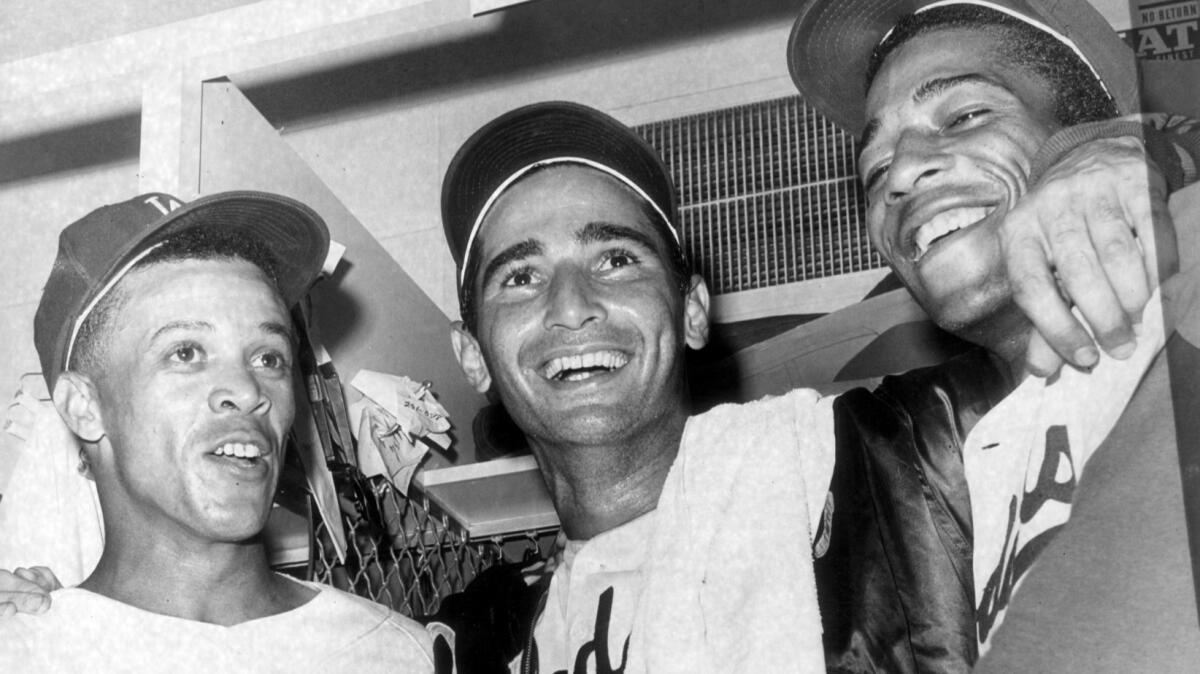

And in an era when the Dodgers relied on pitching, supplied primarily by Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale, and runs were at a premium, every base Wills stole relieved some of the tension. “Playing the Dodgers,” he once said, “one run is a mountain.”

He stole second, he stole third and, when the situation called for it, he stole home. He disrupted pitchers and embarrassed catchers and infielders. Typically, he’d single, steal second, then score on someone else’s single. Or, single, steal second, draw a bad throw and take third, then score on a flyout.

“Maury made himself a superstar. He taught himself not to make mistakes,” former teammate Norm Sherry told The Times in 1980.

Wills might not have been as big a draw as Koufax or Drysdale, but he was right behind them. Legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully described the 5-foot-11, 170-pound Wills as “the mouse that roared.”

With fame, though, came temptation, and slick as he was running the bases, Wills could not outrun temptation. In his autobiography, written with Mike Celizic, “On the Run: The Never Dull and Often Shocking Life of Maury Wills,” he claimed to have had love affairs with Hollywood stars Doris Day — in her autobiography, “Doris Day: Her Own Story,” she denied it — and Edie Adams. He had a volatile and corrosive six-year relationship with a woman named Judy Aldrich and blamed her for getting him started on heavy drinking.

He hobnobbed with entertainers, even playing Las Vegas gigs himself, singing while accompanying himself on banjo, guitar or ukulele, but wasn’t always a clubhouse favorite, even though he was the team captain.

“A lot of our ballplayers just plain didn’t hit it off with him,” then-Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi told Sports Illustrated after Wills was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates. “Maybe he was a little too intense for their taste, I don’t know.”

Still, Wills was a productive player on a winning team and might well have spent his entire playing career with the Dodgers — he did finish with them after stints with Pittsburgh and Montreal — had it not been for an escapade after the 1966 season.

Having just been swept in the World Series by the Baltimore Orioles, the Dodgers embarked on a barnstorming trip to Japan. Wills, who had been bothered by a midseason knee injury, said the knee was hurting and asked to leave the tour, return to Los Angeles and get treatment. Denied permission, he left anyway.

Instead of flying directly to Los Angeles and getting treatment, he stopped for a week in Honolulu, where he joined singer Don Ho in his act, playing his banjo, singing and joking. Bavasi, vacationing in Hawaii with his wife, happened to catch the act one evening, and shortly thereafter Wills was traded to Pittsburgh.

Wills equaled his career high with a .302 batting average in 1967, his first year with the Pirates, and continued to be a productive player throughout his 30s. In 1971 at age 38, he batted .281 with 169 hits in 149 games for the Dodgers. He was released after the 1972 season with 2,134 career hits.

During his playing days, Wills had spent several winters as manager of a Mexican League team, and it was his hope that he would continue his career as a major league manager. He turned down the Giants, who offered him a one-year contract in 1977, and was working on a broadcasting career and serving as a part-time baserunning coach when he finally got his managerial shot.

Maury Wills shares what would have been his thank you speech if he was at the special night honoring him at Dodger Stadium.

The Seattle Mariners, an expansion team then in its fourth desultory season, fired Darrell Johnson in early August 1980 and hired Wills to bail them out. On his first night at the helm, the Mariners lost to the Angels 8-3, falling into last place in the American League West. That was as good as it got for Wills with the Mariners. They finished last, then got the 1981 season off to a 6-18 start, their worst ever, and Wills was gone by early May.

That, coupled with his deteriorating relationship with Aldrich, sent him into a tailspin. He binged on booze and cocaine, locking himself in his house alone, staying high for days at a time, covering the windows with blankets, hallucinating, weathering intense paranoia, contemplating suicide.

Wills estimated that in one year, he spent $1 million on cocaine — and although he became sober in 1989, that descent into darkness might have been part of the reason he has not been elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame. He was rejected 15 times by the Baseball Writers’ Assn. of America and an additional 10 times by a veterans’ committee.

“I do believe I will be inducted,” Wills told The Times in 2016. “The question is whether they are going to induct me before I die.”

The Dodgers helped get him into a drug-treatment program, but Wills walked out and continued to use drugs until he began a relationship with Angela George, who helped him get into a rehabilitation clinic. Wills, again with assistance from the Dodgers, eventually got sober in 1989, and he and George later married.

“Some people get old but never grow up,” Wills said of his dark days. “That’s what happened to Maury Wills. In those three years, I aged 15 years.”

Maurice Morning Wills, one of 13 children, was born Oct. 2, 1932, in Washington. He decided to become a baseball player after attending a baseball clinic conducted by Jerry Priddy, a major league infielder playing for the Washington Senators.

“I didn’t own a pair of shoes,” Wills told the Great Falls (Mont.) Tribune in 2001. “Until that man came to our projects, I didn’t even know we had major league baseball in Washington. But he singled me out. He told me I had some talent. And right then and there, at age 10, I knew I wanted to be a major league player.”

He signed a minor league contract with the Dodgers at 17 and made his debut with them a decade later.

After regaining sobriety, he resumed his coaching duties, most recently with the Dodgers, and devoted considerable time to drug and alcohol education. Wills appeared for the first time as a candidate on the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Golden Era Committee ballot in 2015. Election required 12 votes, and Wills received nine.

At the Dodgers’ spring training facility in Vero Beach, Fla., Wills taught advanced baserunning and bunting techniques in an area of the complex affectionately called “Maury’s Pit.” He also served as color commentator for the Fargo-Moorhead (N.D.) RedHawks in the independent American Assn. for 22 years, retiring in 2017.

He credited the low-key atmosphere in North Dakota for helping him maintain sobriety.

“I’m feeling free,” Wills told The Times’ Kurt Streeter in 2008. “Totally free. No ill feelings, no resentments. ... Peace.”

He is survived by his wife, Carla, and six children: Barry Wills, Micki Wills, Bump Wills, Anita Wills, Susan Quam and Wendi Jo Wills.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.