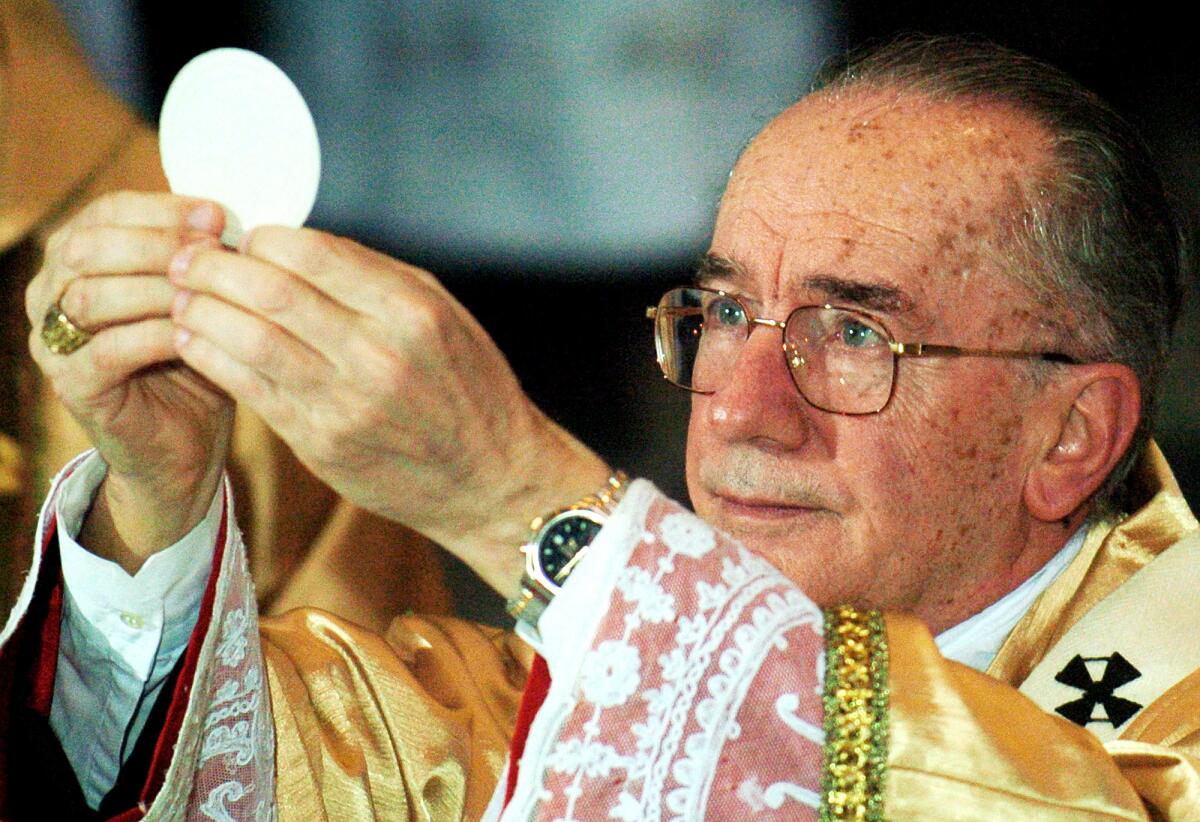

Brazilian Claudio Hummes, once viewed as possible first Latin American pope, dies at 87

- Share via

Claudio Hummes, the Roman Catholic cardinal who championed striking workers in their fight against Brazil’s military dictatorship and who some believed could have become history’s first Latin American pope before Francis earned that distinction, has died. He was 87.

One of Brazil’s most important religious leaders, Hummes died Monday “after a long illness, which he endured with patience and faith in God,” Cardinal Odilo Scherer, the archbishop of Sao Paulo, said in a statement.

Hummes was a close associate of Francis, an Argentine with whom he shared South American roots and a special concern for those in poverty, for the Amazon rainforest and for Indigenous peoples. The Brazilian was said to have whispered words of encouragement when it became clear that then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was about to be elected to the throne of St. Peter, at the 2013 conclave of cardinals, and to have inspired him to pick “Francis” as his pontifical name, after St. Francis of Assisi.

“A great friend, a great friend,” Francis said of Hummes at his first news conference after being picked to succeed Pope Benedict XVI. “When things started getting a little dangerous, he cheered me on. And when the vote came to two-thirds, the usual applause began, as the pope had been elected.

“He hugged me, kissed me and said: ‘Do not forget about the poor.’ Those words were carved on my mind.”

A lifelong cleric, Hummes shot to national prominence in the 1970s as a staunch defender of human rights and social justice under Brazil’s repressive right-wing military regime. He publicly supported and shielded striking metalworkers, one of whom, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, went on to become the nation’s first leftist president a quarter-century later.

The archbishop of the Brazilian city of Manaus, Leonardo Steiner, clearly shares the same ethos and ideology as the pope’s namesake, St. Francis.

“His unconditional love for his neighbor brought him to put himself always on the side of the poor, even in the most adverse situations,” Lula — who is running for president again, in October — wrote on Twitter on Monday.

International attention focused on Hummes in 2005 upon the death of the man who had appointed him cardinal, Pope John Paul II. A veteran Vatican insider, Hummes, then 70, quickly became one of the most-talked-about candidates to assume the papacy, backed by those who saw him as a leader capable of healing some of the church’s internal divisions and shoring up the faithful in poverty-stricken Latin America, home to half the world’s Catholics.

“He is a man of dialogue who has a clear inclination toward the poor,” Frei Betto, a Dominican friar and social activist, said at the time.

“He respects both liberation theology and Opus Dei,” Betto said, referring to liberal and conservative streams within the Catholic Church. He described Hummes as “a moderate with a social sensibility.”

In the end, Hummes’ fellow cardinals elected the German-born Joseph Ratzinger, one of John Paul’s closest aides, as the new pope, disappointing those who had hoped for a pontiff from the developing world.

Hummes worked for the new Pope Benedict from 2006 to 2011 as prefect of the Congregation for the Clergy, the Vatican office in charge of the priestly education and training. He left the job because of age limits.

In Sao Paulo, South America’s largest city and Brazil’s industrial powerhouse, Hummes’ long service as a bishop and cardinal earned him a reputation as an energetic, fair-minded, accessible leader who cared deeply for his flock and knew the diocese’s priests by name.

But he was also a reserved figure, intellectual and cerebral, as comfortable with his books as with people. He lived the simple life expected of a member of the Franciscan order and spoke at least four languages — Portuguese, French, German and Italian — in addition to having mastered Latin.

Italian and Catholic media have been rife with unsourced speculation that the 85-year-old Pope Francis may step down.

A prolific writer, Hummes expounded often on the need for the church to stay socially relevant by engaging with science and with modern technology, such as in the debate over stem-cell research.

He also spoke of the need to be more aggressive in reaching out to Catholics whose only contact with the church was at birth, marriage and death, or who had deserted Catholicism in favor of the Evangelical Protestant sects that have become increasingly popular in Latin America.

“‘They were baptized in our churches — they’re our children, and we have to take care of them,’“ Msgr. Dario Bevilacqua, one of Hummes’ aides, once quoted his boss as saying. Hummes, he said, lamented “how we Catholics have lost the habit of evangelizing.”

Hummes’ own religious training started when he was a young boy. Born Aug. 8, 1934, into a family of German immigrants in southern Brazil, Auri Afonso Frank Hummes was enrolled in a seminary school at age 9.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

He kept up his religious studies, adopted Claudio as his religious name and was ordained to the priesthood five days before his 24th birthday. Hummes went on to earn a Ph.D. in Rome, then worked in various church posts in his home state of Rio Grande do Sul until 1975, when he was given the assignment that would launch him into the national spotlight.

On the fringes of Sao Paulo, the hard-bitten suburb of Santo Andre was already a major manufacturing center by the time Hummes first juddered into town, a newly minted bishop in a dilapidated old car.

“It was a used Volkswagen Bug,” said Father Antonio Moura, Hummes’ close assistant for the next 21 years. “It was kind of embarrassing. He said, ‘I can go anywhere in this car — I don’t need anything fancier.’ And he always drove himself.”

Hummes soon began visiting the metalworkers who were organizing strikes in defiance of the military regime, demanding better wages and greater freedom. Despite his naturally unassuming nature, in August 1976 Hummes came out with the following message: “It’s time for politics.”

Throughout 1978 and 1979, he was vocal in his support of the workers, refusing at one point to act as an intermediary in the conflict. “The church cannot have the role of mediator because it is firmly behind one side — that of the workers,” he said.

In 1980, the government cracked down hard, arresting more than a dozen union leaders. Hummes responded by opening up Santo Andre’s churches, including its ornately painted cathedral, as sanctuaries, giving the movement a place to meet and, more than once, to hide from riot police.

In homily after homily, Hummes preached of the workers’ right to dignity and even allowed their most fiery representative, Lula, the future president of Brazil, to make political speeches during Masses. Ever the spiritual shepherd, Hummes once led a soccer stadium full of persecuted workers in reciting the Lord’s Prayer.

“It was the church that allowed us to remain organized,” Jair Meneguelli, a former labor leader, once recalled in an interview with The Times. “I look at [Hummes] as heroic. In such a difficult moment as during the military dictatorship, he wasn’t afraid of opening up the umbrella of the church’s protection for those he understood to be most in need.”

Evangelicals have become a major force in Brazilian politics. They now make up 30% of the population — double their share two decades ago.

The workers’ strikes helped bring down military rule in 1985. In 1996, Hummes was appointed archbishop of the northern capital of Fortaleza. After more than two decades in Santo Andre, he took with him just two suitcases of clothes.

In 1998, he returned to Sao Paulo as archbishop.

Although he would not regain the national fame he enjoyed during the 1970s and ‘80s, Hummes remained committed to the workers of Brazil, helping to found a job-placement center to help Sao Paulo’s swelling ranks of unemployed.

His advocacy on behalf of the downtrodden seemingly put him in line with left-wing clerics who supported liberation theology, a Marxist-tinged stream within the church that Pope John Paul II rejected and tried to root out. But Hummes spoke out against the theology, saying that the church should not be tied to any particular political ideology.

He was elevated to cardinal in 2001.

When the throne of St. Peter became vacant in 2005, many religious commentators felt that choosing Hummes to fill it would give the church a more conciliatory leader willing to hear dissenting opinions and adopt a more collegial, decentralized power structure within the Vatican than had existed under John Paul II.

But after the College of Cardinals elected Ratzinger, Hummes joined his colleagues in pledging his support to the new pontiff.

When Benedict announced his retirement in 2013, Hummes was no longer among those considered frontrunners to become pope. But in Francis he had a like-minded new leader.

Hummes is to be interred in the cathedral in Sao Paulo.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.