Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s longtime president, dies at 95

- Share via

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — On the eve of Zimbabwe’s national elections in July 2018, Robert Mugabe held a surprise news conference at his sprawling “Blue Roof” compound in Harare, where he’d been confined since his own soldiers ousted him just months earlier.

It was one of the last times reporters would scrum for position to hear the former president, and he sat — fragile and defiant — and complained at length about his treatment since being kicked out of office. His wife, Grace Mugabe, sat to the side and periodically reminded him to stay on message.

It was a typical display of bravado for the iconic freedom fighter and controversial politician — sidelined, disgraced and yet also empowered with the instinctive understanding of his undeniable legacy. If he wanted to speak, people would still listen. And so they did.

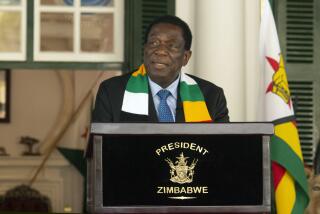

One of the last of Africa’s “Big Men,” Mugabe died Friday in Singapore after an inglorious exit from leadership. Once a respected liberation leader, he had become an international pariah, and the nation cheered when the military took him into custody. He retired in 2017 rather than face the humiliation of impeachment. He died at 95.

When Mugabe took over as Zimbabwean president in 1980, there were wild celebrations for the hero of the liberation war against Britain. After a catastrophic economic collapse sparked by the seizure of white-owned farms, international sanctions and a series of fraudulent elections, Mugabe was still in there. Other than in the few Mugabe strongholds, it was difficult to find a Zimbabwean with a good word to say for him.

Educated and polished, fond of Savile Row suits and with a string of degrees, the rural cattle-herding boy turned English gentleman also impressed Western leaders and journalists when he came to power. If a little cold, he was seen as the brightest hope of the African liberation movement, a vast improvement on his predecessor, the white supremacist Ian Smith.

After the first quarter-century of Mugabe’s tyranny, many ordinary Zimbabweans looked back on Smith’s era with nostalgia, while racists, white farmers, black union officials and priests found themselves on the same side, opposing him.

Millions fled into exile, as much to escape the economic hopelessness as to escape the regime’s repression.

In his final years Mugabe was frequently photographed snoozing during important African summit meetings — clinging to power, though barely able to stay awake.

His tenure came to be defined by a question: How did this intelligent, promising leader turn out to be such an embittered, ruthless leader?

There were many pop-psychology theories: Was it the harsh family background with a father who deserted him, refusing to even pay school fees, and his strict, remote and pious Roman Catholic mother? Or was it the death of his first wife, Sally, seen by many as a gentle moderating influence? Some suggested it was jealousy of the region’s bright star, Nelson Mandela, the globally adored South African leader who, like Mugabe, embraced violence in the liberation struggle but came to be a peacemaker.

But others, like the author Martin Meredith, who wrote “Our Votes, Our Guns: Robert Mugabe and the Tragedy of Zimbabwe,” argue Mugabe was always a tyrant, from the beginning of the liberation struggle. In Mozambique, where he and other liberation fighters fled into exile, he was ruthless with rivals and dissenters alike.

The defining quality of his leadership was his response to any political threat. He struck hard, using violence and fear to crush opponents. People in the ruling ZANU-PF party who opposed his drive for one-party rule in the 1990s had mysterious car “accidents.”

As liberation movements mushroomed across Africa during the Cold War, when America and the Soviet Union divided up the continent and fought proxy wars on foreign soil, South Africa’s African National Congress drew its Marxist inspiration from Moscow. But Mugabe turned to China and North Korea, which trained his notorious Fifth Brigade.

The list of abuses is not short. The motive, almost invariably, involved consolidating power or crushing dissent.

There was Gukurahundi — Shona for “the early rain that washes away the chaff before the spring rains” — an early 1980s rampage by the Fifth Brigade that left thousands dead in Matabeleland in southern Zimbabwe.

In 2000, rural farm workers and white farmers were attacked and had their land confiscated after Britain went back on a promise to compensate white farmers so that land could be transferred to blacks. There was another side to it, analysts argued: Mugabe perceived white farmers as the enemy, because they had sided with the opposition, and was determined to crush them.

There was Operation Murambatsvina (“clean out the filth”) in 2005: About 700,000 shack dwellers in urban opposition strongholds were forced from their homes by the army. Their houses were razed, and they were ordered into the countryside. Thousands suffering from HIV/AIDS died in rural areas or the outskirts of towns with no access to doctors or treatment. Others never recovered financially.

In 2007, facing election defeat, Mugabe unleashed another campaign, setting up military base camps across the country, kidnapping and beating and killing opposition supporters.

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was born Feb. 21, 1924, in a rural village in what was then Southern Rhodesia. He was a loner and a bookworm who shunned other children. He was educated at a Catholic mission, and the local priest, Father Jerome O’Hea, was convinced he was leadership material. His mother, Bona, had high expectations.

Mugabe traveled to Ghana and met teacher Sally Hayfron in 1960, marrying her in 1961. The descriptions of his domestic life by Sally’s niece Patricia Bekele contained in Heidi Holland’s book “Dinner With Mugabe” suggest a blissful time. In the early 1980s he would come home to Zimbabwe’s State House, calling for Sally, slamming the doors so she would hear he was home and come quickly to him. He’d sit in the garden with her, reading a Graham Greene novel and occasionally kissing her.

They spent their early years of marriage apart. In 1964, he was jailed for 10 years as one of the movement’s leaders. His first son was named Nhamodzenyika, which means “suffering country,” and died in 1966 in Ghana with Sally while Mugabe was in prison. He was not allowed to go to the funeral.

In 1975, Mugabe fled into exile in Mozambique, where he led ZANU-PF in its bush war against Smith’s white-minority government.

Mugabe was at the center of the talks in Britain that ended the bush war and set the scene for Zimbabwe’s democratic elections in 1980. Under the deal, Mugabe promised reconciliation with Rhodesian whites, offering them 20% of seats in parliament for the first 10 years. He believed he had a binding verbal promise that Britain would help pay the cost of compensation to white farmers, who were to be removed on a “willing buyer, willing seller” basis, a deal the British repudiated in 1997.

Dumiso Dabengwa, a senior ZANU-PF official who left the party in 2008 and died in 2019, said earlier that the West ignored the violence and beatings Mugabe unleashed in the first elections — particularly inMatabeleland, where people were loyal to the rival liberation movement, ZAPU.

The violence went unreported in the Western media — like the Matabeleland massacres that followed. According to witnesses, villagers were locked into huts and burned alive. Men were seized, tortured and killed. Estimates of the number killed range from 2,000 to 20,000.

Mugabe made a peace deal with the ZAPU leader, Joshua Nkomo, in 1988, merging the two movements, but in reality ZANU simply gobbled up ZAPU.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, determined to implement a one-party state, he sent senior party cadres to North Korea, where they were supposed to be impressed by the system. Instead, they were horrified by what they saw and returned opposed.

In 1992, Sally died of kidney disease, and in 1996 Mugabe married his secretary: Grace Marufu, 30 years his junior, disliked in Zimbabwe for her taste in Italian shoes and lavish shopping sprees abroad.

Mugabe held no fewer than seven degrees, but he was a Marxist ideologue, with little comprehension of the impact of land reform and cash grants to war veterans.

Under pressure from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, he introduced painful economic reforms in the early 1990s, causing job losses and inflaming dissent. Coupled with several years of severe drought, Mugabe faced unemployment, poverty and serious opposition.

Veterans, who had been promised land in return for their independence war effort, grew restless and demanding. In 1997, he agreed to pay 50,000 Zimbabwean dollars apiece to each of the 45,000 unemployed war veterans (enough to buy a house or business) and a monthly pension of 2,000 Zimbabwean dollars. The dollar crashed overnight and the economy was crippled.

Zimbabwe’s first opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change, led by a union leader named Morgan Tsvangirai, sprang from the anger over the impact of the economic reforms. Soon after the MDC’s formation, security operatives invaded Tsvangirai’s office in a multi-story building and tried to throw him out the window. (Tsvangirai died in 2018.)

Mugabe tried to widen his presidential powers in a 1999 referendum, but the MDC campaigned heavily against him, supported by the checkbooks of white farmers. He lost: his first defeat.

Stunned, he lashed out at the MDC and white farmers. MDC activists were arrested, tortured and killed.

Feeling betrayed by Britain after the repudiation of the deal to pay compensation to white farmers, he invited war veterans to take farms. Thousands of white farms were seized by war veterans without compensation, white farm families were terrorized and some 300,000 black farm workers were left jobless. Many were beaten, raped or killed.

Later, the farms were taken from veterans by ruling-party stalwarts, including generals, judges, intelligence chiefs and members of Mugabe’s family. Farming collapsed, and the agriculture-based economy in what was once the breadbasket of southern Africa went into severe decline. The move to quash title deeds had a catastrophic effect on investment — destroying the economy, although Mugabe always blamed Western sanctions for his economic problems.

The tobacco industry, one of the main earners of foreign exchange, shrank quickly as farms were seized and production plummeted. Mugabe responded by printing money. Zimbabwe had the highest inflation ever known, more than 200 million percent. Notes lasted just days before they became unusable.

Mugabe’s brother liberation leaders, such as South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma, were supportive, wary of a union-based opposition movement defeating a liberation movement. But they did force some electoral changes on Mugabe, making it hard for him to manipulate results in the 2008 presidential election.

When results indicated a runoff between Mugabe and Tsvangirai, and huge losses in ZANU-PF’s heartland, Mugabe’s thugs came out again. Mugabe claimed victory but was eventually forced by African leaders to implement a government of national unity with Tsvangirai and other opposition figures.

In 2013, Mugabe again won reelection in a ballot tainted by widespread allegations of voter fraud. His frequent trips abroad for medical care stirred controversy.

By 2017, he had become so unpopular that the military staged a coup and took Mugabe and his wife — who had had her eyes on succeeding her increasingly frail husband — into custody. Within days, impeachment proceedings began and Mugabe, realizing he now had little room to maneuver, resigned. He was granted immunity and, again at government expense, was provided a five-bedroom house and a staff that included cooks, secretaries and armed guards, though he spent much of his final years hospitalized.

Mugabe is survived by his wife, Grace, and three children, Bona, Robert and Bellarmine Chatunga.

Special correspondent Krista Mahr in Johannesburg contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.