Former Chargers linebacker Junior Seau dies in apparent suicide

Through her tears, Luisa Seau said that there had been no warning of this. How could her son, Junior, who had so much promise in his life and during a glittery football career, want to kill himself? âI donât understand,â she wailed.

But Seau, 43, a star linebacker at USC and for his hometown San Diego Chargers, apparently ended his life Wednesday with a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his Oceanside home.

Oceanside Police Chief Frank McCoy said Seauâs girlfriend went to the beachfront home about 9:30 a.m. and found him dead in a bedroom. Police and paramedics tried unsuccessfully to resuscitate him.

McCoy said Seau died of a gunshot wound to the chest. A handgun was found near the body. The case is being investigated as a suicide, although police found no suicide note. A crowd of media and onlookers gathered outside the home Wednesday morning.

Seauâs ex-wife, Gina, said that on Tuesday he sent her and each of their three children â daughter Sydney and sons Jake and Hunter â a text message, ending with âI love you.â

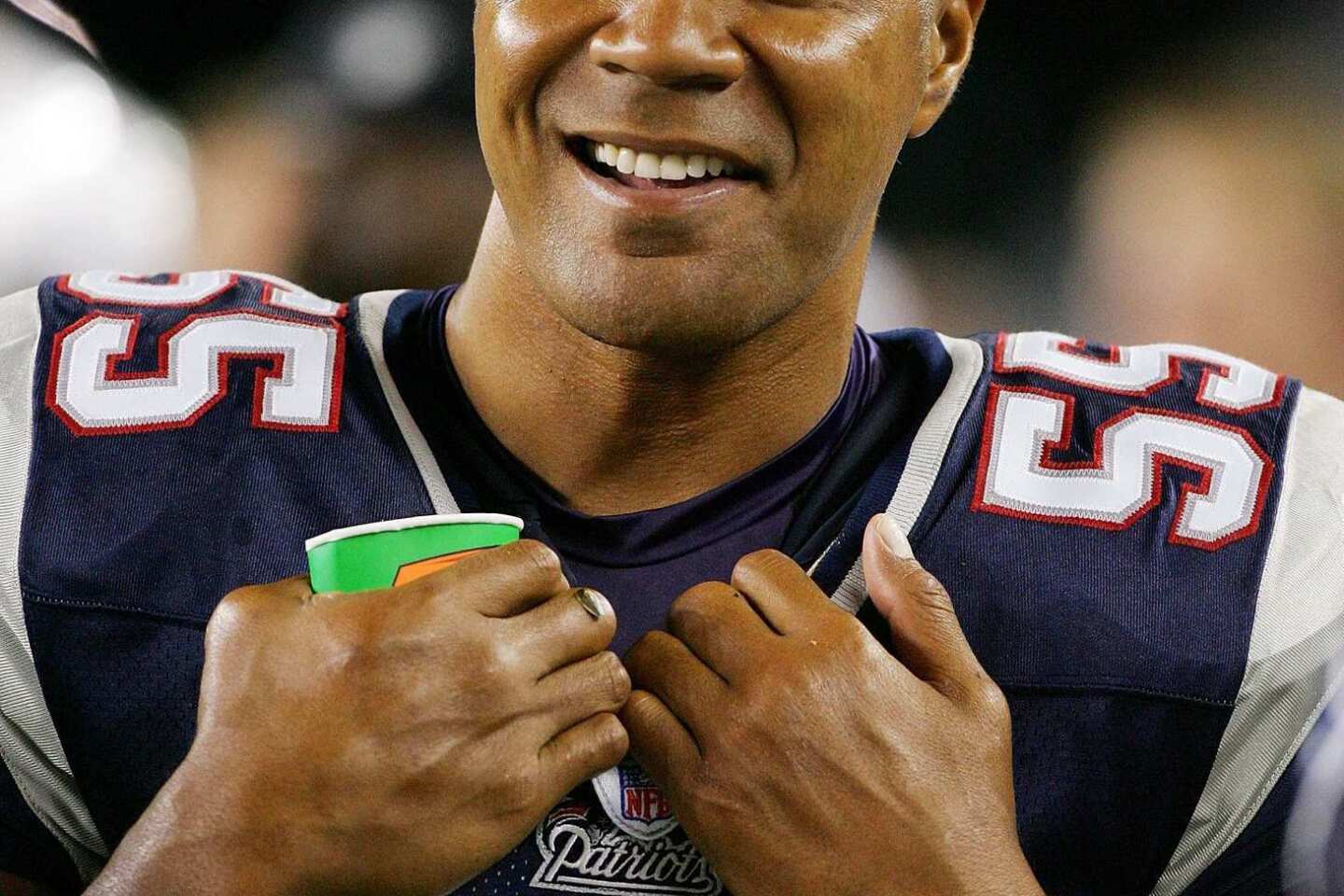

Seau, an All-Pro linebacker who spent most of his 20-year NFL career with the Chargers, retired in 2006 and then âunretiredâ several days later, saying he was not ready to leave a game that he loved. He retired for good after the 2009 season.

On Wednesday, some saw similarities between the deaths of Seau and former Chicago Bears safety Dave Duerson, who died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest last year. In a suicide note, Duerson had asked his family to donate his brain to the Boston University School of Medicine.

Researchers from that school later determined that Duerson suffered from a neurodegenerative disease linked to concussions, and that played a role in triggering his depression. The San Diego County medical examiner said an autopsy for Seau is set for Thursday.

Seau will be remembered as one of the greatest players in NFL history at any position, a 6-foot-3, 248-pound wrecking ball who made the Pro Bowl 12 years in a row and was voted All-Pro 10 times. He often veered from the script on the field, and that only made him more effective.

Christian Fauria, a longtime NFL tight end, said opposing offenses frequently could not rely on scouting reports when it came to lining up against Seau.

âMost of the time he would just kind of go where he thought the ball was going,â Fauria said. âHe would disregard every bit of coverage rules and gap assignments. He would just go to where he thought the play was going, based on what he looked at, what he saw.â

That was the case at Oceanside High, where Seau dominated in football, basketball and track, and at USC, where his No. 55 jersey became synonymous with the gold standard of linebackers.

He had humble beginnings with the Trojans, however, having entered the school ineligible for his freshman season because of low test scores coming out of high school.

He later said he initially felt like an outsider at the school and harnessed that as motivation.

âIt was terrible,â he told The Times in 1991. âI used to walk the campus and not be part of the inner circle. I had no friends. The guys would be mingling on the steps, and that would be the inner circle and they didnât accept me. They were USC. They were the players, and they were looking at a guy who didnât pass his SATs.â

After an ankle injury limited his contributions as a sophomore, Seau broke through as a junior and became a unanimous first-team All-American. He made the then-rare decision to forgo his senior season and enter the NFL draft.

âIt was a money decision,â he later explained. âI had the security of my mom and dad in my hands. I donât know how my dad made it, paying the bills while we were growing up, but I owe everything to him and my family.â

The Chargers made the 20-year-old Seau the No. 5 pick in the 1990 draft, worried only that he might be gone before they had a chance to select him. As was the case at USC, Seau did not feel immediately embraced by his teammates. He felt shunned because he was a contract holdout in his first training camp.

He experienced an attitude shift in the seventh game of his rookie season, against the Los Angeles Raiders, when he had successfully called a defensive huddle. His team was not victorious on that day, but, in a way, Seau was.

âMy dad called me and said, âOh, sorry you didnât win,â â Seau recalled years later in an interview with the South Florida Sun-Sentinel. âI said, âDonât worry, I won. They huddled for me.â That is what I would call a turning point in my career.â

The following year, he made the first of his 12 consecutive Pro Bowls. But the Chargers had only sporadic success during his time with them, posting non-winning records in 10 of Seauâs 13 seasons. The franchise did make its only Super Bowl appearance, however, when he was on the team, losing to San Francisco in January 1995.

âI donât think there will ever be anybody who will be able to match what this guy was able to do on the football field,â said longtime Raiders receiver Tim Brown. âHe was big, fast, smart, strong and fearless. You put all that in a weak-side linebacker, and youâve got somebody whoâs scary. For many, many years he was just that for us.â

Seauâs career with the Chargers came to a close in April 2003, when the team traded him to Miami for a conditional draft choice. He wound up starting 15 games for the Dolphins and made 133 tackles. But the following year, he was sidelined for eight games with torn biceps. That was only one fewer game than he had missed in the previous 14 seasons combined.

The time away from practices and games took its toll.

âIâll tell you what, there are a lot of minutes in the day,â he told reporters in Miami in 2005. âI know that now. I definitely got a little taste of what itâs going to be like when the game is done. Itâs something Iâm not ready for.â

The next season it was an Achilles tendon injury that ended his year, and in August 2006, he retired after signing a ceremonial one-day contract with the Chargers. His playing days were not over, however. Just four days later, he signed with New England and wound up playing the better part of four seasons with the Patriots.

Tiaina Baul Seau Jr. was born Jan. 19, 1969, in Oceanside to Tiaina Baul and Luisa Seau, natives of American Samoa. One of six children, Junior Seau spent several years with his family in his parentsâ homeland, but most of his youth was spent in Oceanside, where his father was a high school janitor.

He enrolled at USC in 1987 determined to escape the kind of street violence that swirled around others in the Samoan community. A 16-year-old cousin was killed in an apparent gang shooting in 2005.

After retiring from football, Seau remained in the public eye: appearing at his sports-themed restaurant in San Diego, raising money for youth groups through the Junior Seau Foundation and playing in his annual charity golf tournament.

âAs great a football player as Junior was, he was a greater human being,â the Rev. Shawn Mitchell, the Chargersâ chaplain for 28 years, said Wednesday.

In October 2010, Seau drove his sport utility vehicle off a 30-foot coastal bluff in Carlsbad in the hours after an argument with his girlfriend. He told police that he had fallen asleep while driving; he was treated at a local hospital for minor injuries and released.

Oceanside police arrested Seau on suspicion of domestic violence, but the San Diego County district attorneyâs office declined to file charges.

Former Chargers General Manager Bobby Beathard, who drafted Seau, was among those shocked by his death. âThe whole time I was in the NFL ⌠I donât know if Iâve ever seen anybody like Junior ⌠that had it all,â Beathard said. âJust a great guy. He loved playing the game. He loved his teammates. He loved life. I certainly canât understand what went wrong or what happened.â

Perry reported from Oceanside, Farmer from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.