NCAA tournament, then NBA stardom: UCLA star’s dad mapped out a dream

Ron Holmes has spent two decades guiding his son Shabazz Muhammad toward a pro basketball career. The payoff is near, with the UCLA star projected as a top draft pick.

- Share via

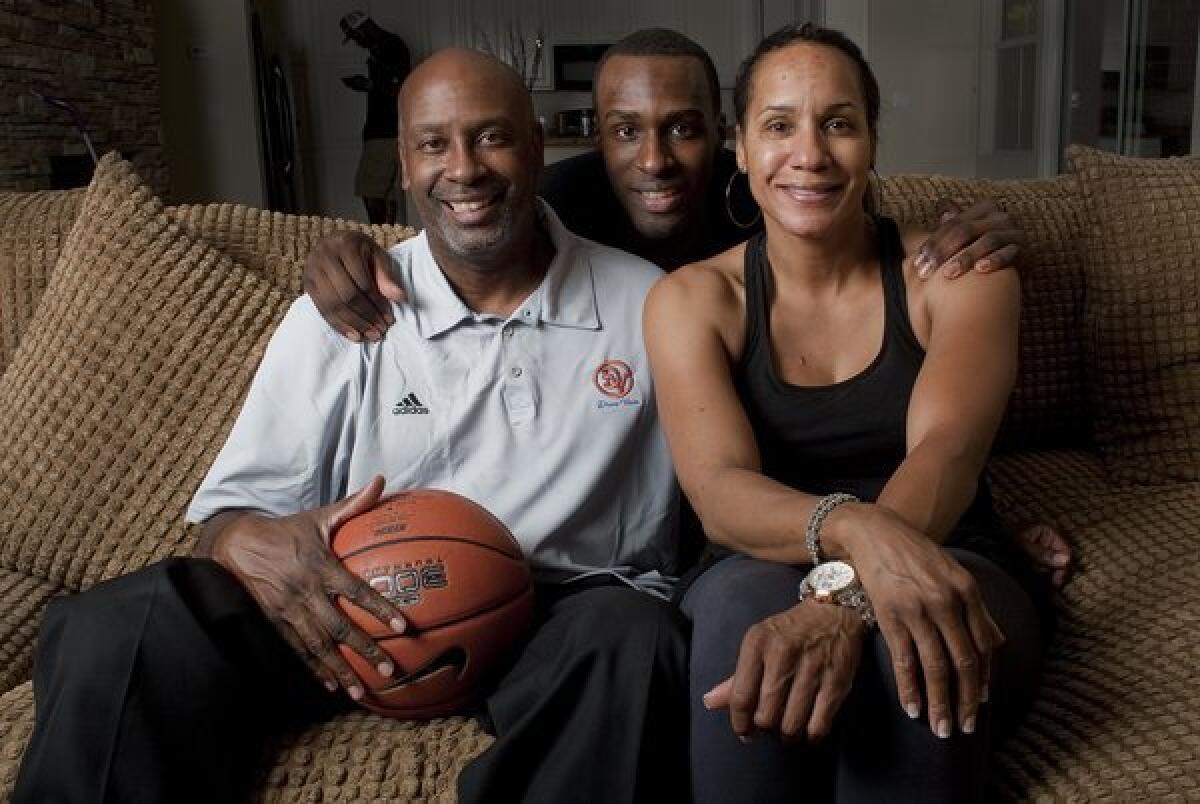

Shabazz Muhammad with his parents, Ron Holmes and Faye Muhammad. (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) More photos

When UCLA takes the court Friday night against Minnesota in its NCAA basketball tournament opener, fans may be getting their last look at Shabazz Muhammad in Bruin blue and gold.

Every thunderous dunk and arching three-pointer will help show why he led the team in scoring, made first team All Pac-12 and was named the conference's freshman of the year. But win or lose, there is little doubt that the explosive swingman will soon leave Westwood for the pros.

His father, Ron Holmes, has spent two decades making sure of that.

Hoops lovers fixated on Muhammad highlight reels have missed the real show. Off the court, Holmes has been putting on a clinic on how to mint an NBA millionaire.

He made sure Muhammad worked out with some of the sport's finest trainers. He enrolled his son in one of the nation's best high school basketball programs. He helped create a team tailored to showcase his boy's strengths in the high-profile summer circuit. And somewhere along the line, a year was shaved off his son's stated age, giving Muhammad an edge over players in his age group.

But Holmes' real genius has been navigating the cutthroat realm of college basketball. It's a world in which school athletic departments, coaches and TV networks reap millions while young athletes, in Holmes words, are left with "crumbs."

Update: Shabazz Muhammad's new age (20, not 19) could hurt draft status

The father decided long ago that he would make the system work for him. For years, Holmes has tirelessly promoted the Shabazz Muhammad brand to scouts, journalists, money managers and others. Holmes navigated every difficulty, including a potentially devastating NCAA sanction that ultimately sidelined his son for only a few games.

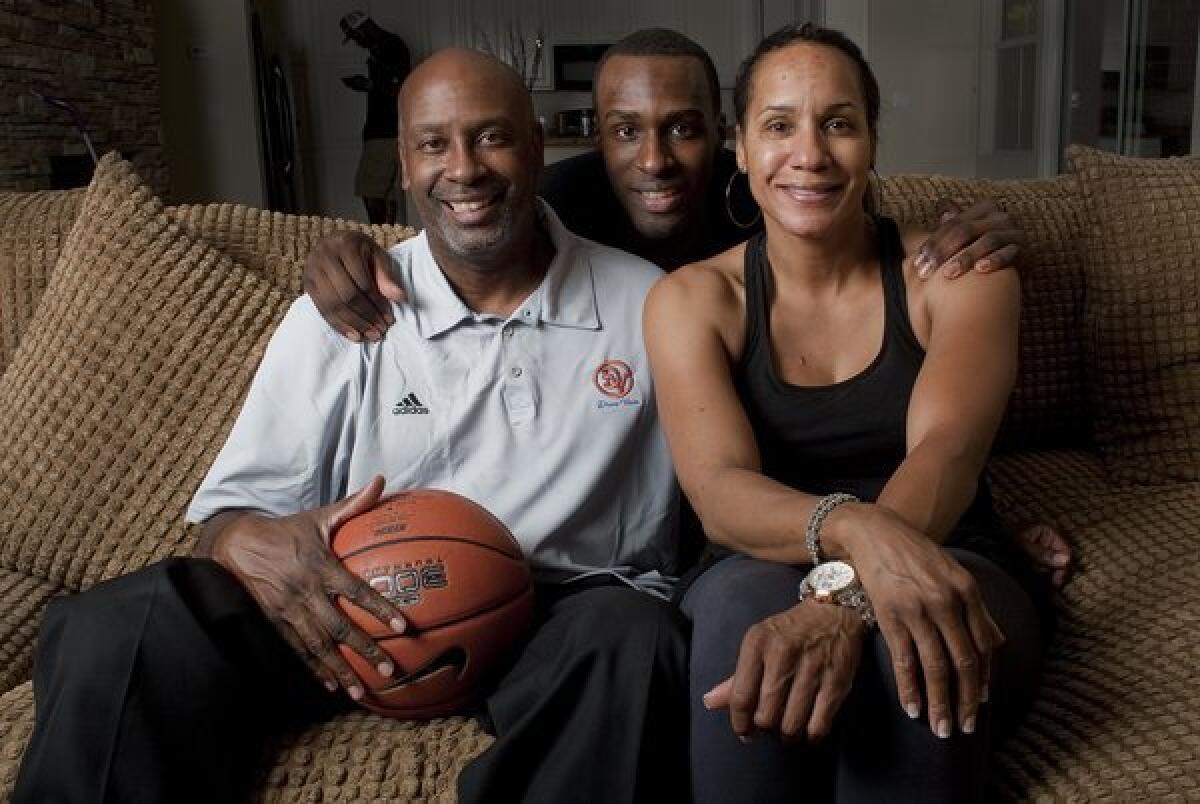

In the early 1980s, Ron Holmes played as a standout guard for USC. Holmes is pictured here in a 1985 game against UCLA. (Los Angeles Times) More photos

With Muhammad now projected as a top-five pick in June's NBA draft, Holmes' investment is about to pay off.

"Basketball is a business, and he handled everything — all the coaches, all the scouts," said Grant Rice, Muhammad's coach at Bishop Gorman High School in Las Vegas. "He took care of his son."

The selling of Shabazz began before he was born.

In the early 1980s, Holmes was a 6-foot-5 standout guard for USC. He never made it to the pros. But he was already thinking far into the future.

As a student, Holmes said, he found himself fascinated by the careful breeding of thoroughbreds, the way that two fast, powerful horses could be crossed to create an even faster, more powerful colt.

Around that time he met Faye Paige, a point guard, sprinter and hurdler at Cal State Long Beach. Spotting her at a summer league game, Holmes recalled saying to a friend: "See that No. 10? She's going to be my wife, and we're going to make some All-Americans."

A few years later, the couple converted to Islam and changed their names. Paige became Faye Muhammad; Holmes tried several handles, including Ronald Muhammad, Ron Shabazz and Rashad Muhammad.

Today, he goes by Ron Holmes because, he said, he never finished his formal religious conversion. Court records show that Holmes used numerous aliases over the years but agreed to stick to his birth name as part of a 2000 probation agreement. In that federal criminal case, he pleaded guilty to using phony bank statements and tax returns to secure mortgages. He served six months' house arrest.

These days, the family lives in a rented home in a gated community in Las Vegas.

See that No. 10? She's going to be my wife, and we're going to make some All-Americans."— Ron Holmes, Shabazz Muhammad's father

"Ron's always been middle class and had money," said Clayton Williams, coach of Dream Vision, Muhammad's summer league Amateur Athletic Union team and a friend of Holmes since the 1980s. "He takes care of his family. They've always lived in nice houses and driven nice cars."

By his account, Holmes, 51, supports his family with income from rental properties that he and associates purchased in California and Nevada about 15 years ago. Holmes declined to identify the properties, which he said are not in his name.

Holmes' life mission, though, has been to raise his three children to be professional athletes.

"If you're a doctor, your kid is going to med school. If you're a lawyer, he's going to law school," Holmes said. "I was an athlete. That's what I could do for my kids."

He even picked their names based on what "would sound good and be marketable worldwide," he said in one of several interviews with the Los Angeles Times.

Their first child, a daughter named Asia, was born in 1991. At Holmes' urging she took up tennis at age 7, landed an endorsement contract with Adidas at 17 and went pro. Now 21, she still labors in the sport's lower rungs.

Their youngest, Rashad, is a high school senior, a late bloomer on the basketball court who averaged more than 19 points a game this season and hopes to play college ball.

Holmes has pinned most of his hopes on the middle child, Shabazz.

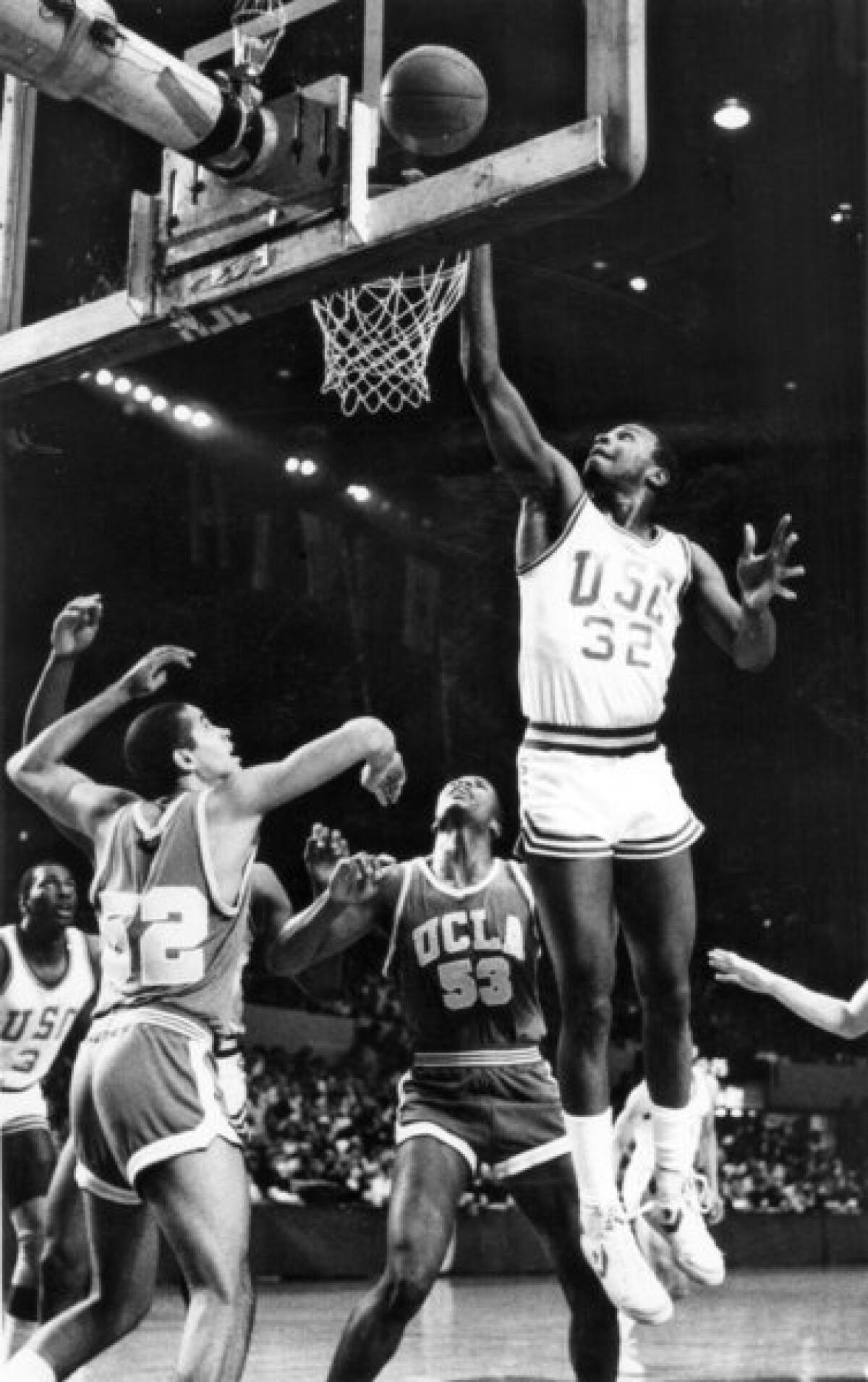

UCLA guard Shabazz Muhammad runs upcourt after scoring a key basket against Stanford in January. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

According to the UCLA men's basketball media guide, he was born in Los Angeles on Nov. 13, 1993.

But a copy of Shabazz Nagee Muhammad's birth certificate on file with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health shows that he was born at Long Beach Memorial Hospital exactly one year earlier, making him 20 years old — not 19 as widely reported.

How and when he lost a year of his life are unclear. But competing against younger, smaller athletes, particularly in the fast-growing years of early adolescence, can be "a huge edge," said Eddie Bonine, executive director of the Nevada Interscholastic Activities Assn. "People naturally look at the big, strong kids."

Asked about the discrepancy, Holmes insisted his son was 19 and born in Nevada. "It must be a mistake," he said.

Several minutes later, he changed his account, saying that his son is, in fact, 20 and was born in Long Beach.

Holmes expressed concern about disclosure of his son's true age and his own criminal record and questioned whether either was newsworthy. He followed up with a text message.

"Bazz is going to blow up in the NBA lets team up and blow this thing up!!!" Holmes wrote to this reporter. "I'm going to need a publicist anyway why shouldn't it be you. We can do some big things together."

College basketball is a vast and profitable industry, bringing billions of dollars to universities, the NCAA, television networks, coaches and other commercial interests.

For players, the chance to earn big money comes with a pro contract. Since 2006, NBA rules have required them to wait a full year after high school to declare for the draft.

For most of the nation's elite players, that means spending a single season playing college ball. That "one-and-done" year amounts to an audition for the NBA.

Bazz is going to blow up in the NBA lets team up and blow this thing up!!! … I'm going to need a publicist anyway why shouldn't it be you."— Ron Holmes, Shabazz Muhammad's father, to a reporter

Holmes was determined to optimize his son's chances.

Driven by his father, Muhammad spent countless hours in the gym. Because his son suffered from a mild case of Tourette's syndrome, which can cause tics and other problems, Holmes told him he had to work that much harder.

Very few freshmen at Bishop Gorman, a $12,000-a-year Catholic high school in Las Vegas with a powerhouse athletics program, make the varsity basketball team. Muhammad was one of them. And when he dropped 29 points against local rival Durango High School a few months into the 2008-09 season, the hoops world began to take notice.

While other teenagers bagged groceries after school, Muhammad crisscrossed the nation, attending dozens of camps and tournaments where scouts would tweet about his progress, post videos and document his ascent in the newsletters they peddle to college coaches.

"Shabazz Muhammad is an 'Alpha Male,'" reads a June 2011 tweet by Las Vegas scout Christian "Pop" Popoola, who sells his reports to more than 50 colleges for $1,000 a year. "Best player in the country, without a question."

Visiting as many universities as possible was also key. Every time Muhammad set foot on campus — any campus — the basketball world took note. In all, Muhammad made more than 15 college visits.

That much travel wasn't cheap, and picking up the tab didn't fit Holmes' philosophy. "When you're good enough, you don't have to pay for your trips," he said.

Others would.

Travel for Muhammad's summer league team, Dream Vision, for example, was funded in part by Adidas, which signed on as a team sponsor after Muhammad rose to national prominence in 2010.

A Los Angeles basketball trainer paid for a trip to the University of Memphis, records show, and a New York financial advisor donated an undisclosed sum to Dream Vision in hopes of getting close to Muhammad.

Another important source of travel funds was a 34-year-old financial planner named Ben Lincoln.

The son of a high school coach and a former student manager of the University of South Florida basketball team, Lincoln runs his own wealth management firm in Charlotte, N.C. A basketball fanatic, he travels the country watching games. His client list includes former college coach Brad Greenberg.

Through his brother, an assistant coach at Muhammad's high school, Lincoln met Holmes. He now calls him a close friend. Starting in March 2010, Lincoln paid for at least three visits to the University of North Carolina and Duke, covering airfare and hotel bills for Holmes and his son.

Lincoln was in L.A. this month to watch UCLA play. In an interview, Lincoln said he couldn't remember exactly how much he spent, but that he paid for the trips because the family was tight on funds, something Holmes denies.

"Ben offered to pay, so I let him," Holmes said.

As a high school freshman, Muhammad received a scholarship offer from the University of Nevada-Las Vegas. By the end of his sophomore year, he was one of the nation's top-rated players. Nearly every serious basketball program in the country wanted him.

Duke and Kentucky, both perennial powerhouses, courted Muhammad. They were on his short list.

While a UCLA recruit, Shabazz Muhammad watches from the bench as the Bruins play against Indiana State in 2012. (Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) More photos

Instead, he chose UCLA.

The university's strategy to land Muhammad included hiring assistant coach Phil Mathews from the University of Nebraska in early 2010.

Known as a strong recruiter, Mathews gave UCLA a distinct edge in the pursuit of Muhammad — he was friendly with the player and his father. His son Jordan played alongside Muhammad on the Dream Vision team. That allowed Mathews to attend practices and games that were off-limits to other recruiters under NCAA rules.

UCLA last year paid him $205,000. That's about $50,000 more than the school's second-highest-paid assistant and 60% more than what Mathews had been making at Nebraska.

Holmes praised UCLA's hiring of Mathews as a clever tactic, what he called "part of the game." But in the end, he said, the family's choice of UCLA "was strictly a business decision."

Westwood is close to Las Vegas, making it easy for Holmes to attend games. The team also had little depth. Head coach Ben Howland would have no choice but to showcase Muhammad, Holmes said. At Duke or Kentucky he would have had to share the spotlight or even risk sitting on the bench.

Also, expectations were low. "If Shabazz takes UCLA past the first round of the tournament, that's a success," Holmes said. "It shows that he's a winner."

Before Muhammad could take the court, however, there was a significant hurdle to clear.

In early 2011, NCAA investigator Abigail Grantstein had grown suspicious of the campus visits paid for by several people, including Lincoln. That December she contacted colleges recruiting Muhammad to alert them that the player may have violated amateurism rules and could lose his eligibility.

On Nov. 9, 2012, hours before UCLA's opener against Indiana State, the NCAA ruled Muhammad ineligible for accepting travel and lodging from Lincoln that it later valued at $1,600.

Then, on Nov. 9, 2012, hours before UCLA's opener against Indiana State, the NCAA ruled Muhammad ineligible for accepting travel and lodging from Lincoln that it later valued at $1,600. That sidelined him indefinitely while the NCAA and the university negotiated an appropriate penalty.

Holmes was frustrated. He was also prepared.

Three months earlier, a Memphis lawyer happened to overhear a conversation on an airplane by a man professing to be Grantstein's boyfriend. According to the lawyer's account, the boyfriend boasted Grantstein was going to ensure that Muhammad would sit out the entire season.

Outraged, the lawyer wrote a letter to a former member of the NCAA infractions committee that went unanswered. She also sent a copy to Robert Orr, the lawyer representing Muhammad in the investigation, and to UCLA.

As the season began with his son on the sidelines, Holmes said he hatched a plan to leak the letter to the media.

If that failed, he said, he had a backup plan: For more than two years, he had been guarding a recording of a phone call that his benefactor Lincoln had made to the NCAA. On the secretly taped call, an eligibility official seemed to approve Lincoln's funding of the trips to North Carolina.

Holmes considered the tape "a little protection" in case NCAA officials questioned the arrangement.

Just days after the NCAA's ruling, the letter was passed to a sports writer at the Los Angeles Times. On Nov. 14, the newspaper published a story about the airplane conversation, with Orr quoted as saying that it "calls into question the impartiality" of the NCAA's decision.

The sports world exploded with accusations that Shabazz had been unfairly judged. Two days later, the NCAA reinstated Muhammad, clearing him to play immediately after having missed three games.

The NCAA does not release documents from investigations. UCLA has refused requests to view the records. A UCLA spokesman declined requests for interviews with Howland, Mathews and Muhammad.

In mid-December, the NCAA fired Grantstein. The association has not offered an explanation for the dismissal, and a spokeswoman declined to comment.

"She came at me," Holmes said. "I did what I had to."

The NCAA tournament is Muhammad's last chance to shine in front of a national TV audience before the NBA draft in June. Draft order translates into millions of dollars. The higher the better.

Near courtside for Friday night's game in Austin, Texas, Holmes will be pushing, like he always has, driven to make his son the professional athlete that he never was.

Asked about his own missed shot, Holmes hesitated.

"I never had the proper guidance," he said. "Nobody showed me the way."

Update: Shabazz Muhammad's new age (20, not 19) could hurt draft status

Document: Shabazz Muhammad's birth certificate

UCLA: Follow the Bruins run for the NCAA championship

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.