Protesters celebrate after top University of Missouri leaders resign over racial turmoil

- Share via

Reporting from Columbia, Mo. — The campus coup d’etat was over.

After two top University of Missouri system officials announced their resignations Monday following allegations that they had not sufficiently addressed racial issues on campus, students danced on the quad where activists had set up a tent city. The football team announced that it was ending its strike and would resume practicing for this weekend’s football game.

At an outdoor amphitheater, hundreds of students chanted in the sun, “I ... am ... a … revolutionary!” Social media users around the world joined in, tweeting more than 100,000 times about the day’s protest.

TIMELINE: The last 58 days at the University of Missouri >>

The uprising was partly a ripple effect from last year’s protests in Ferguson, Mo. Missouri again proved itself a cauldron for black radicalism, with students pairing bold physical protests with a social media megaphone to demand a renewed focus on racial inequality from their university administration.

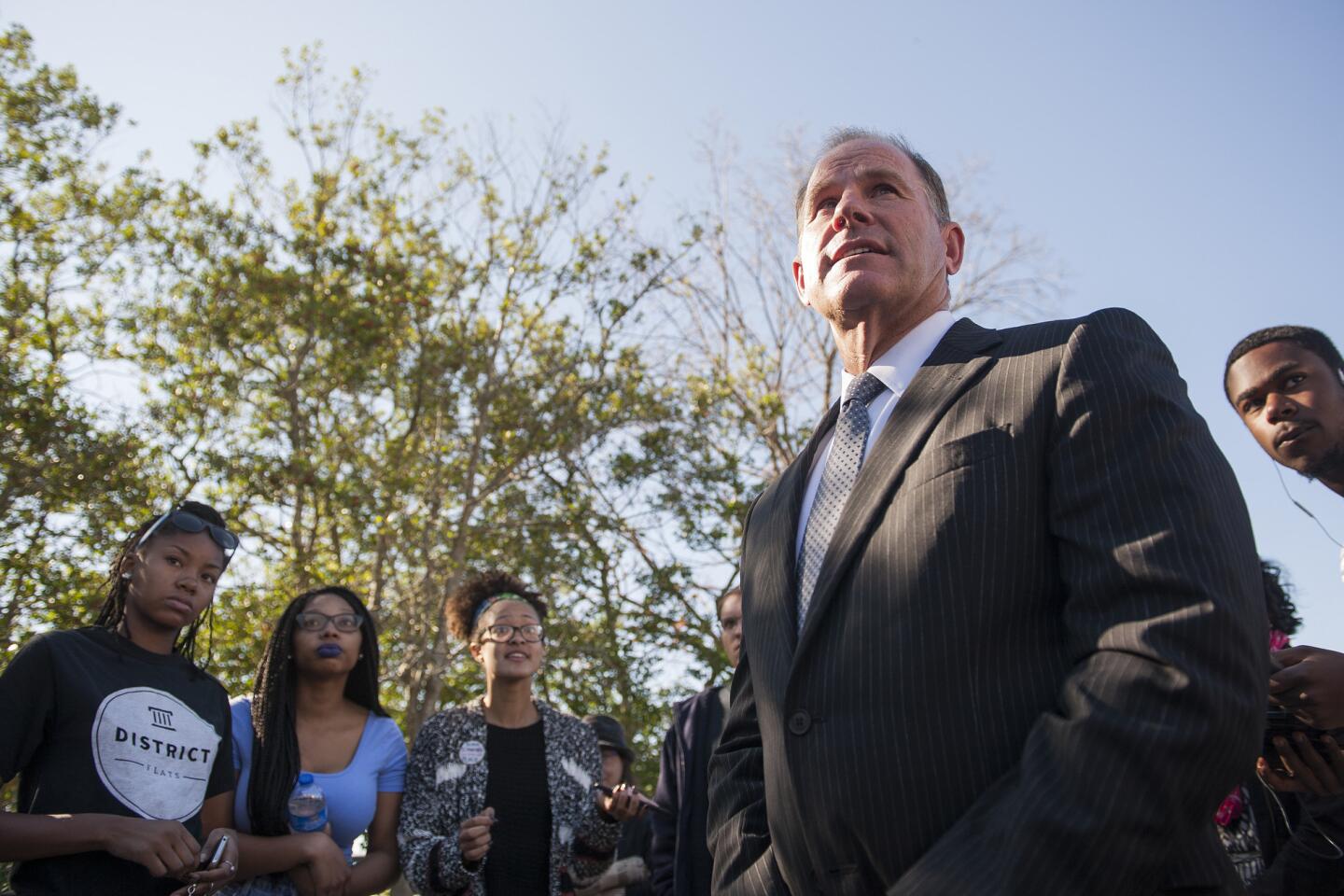

“The frustration and anger that I see is clear, real, and I don’t doubt it for a second,” said university President Tim Wolfe as he resigned Monday morning at a meeting of the system’s governing body, the Board of Curators.

“I take full responsibility for this frustration and I take full responsibility for the inaction that has occurred,” said Wolfe, a businessman who took charge of Missouri’s public university system in 2012. “Use my resignation to heal and start talking again.”

Several hours later, the University of Missouri’s chancellor, R. Bowen Loftin, also announced that he would step down from leading the campus and take a different job coordinating research efforts at the university. He, too, had been criticized for not approaching racial problems more aggressively.

“We take our responsibility very seriously,” Board of Curators Chairman Donald L. Cupps told reporters. “The situations that have occurred in the past few months have been eye-opening for us.”

Student activism is nothing new, and not even something uncommon this semester: Similar protests over racist incidents took place at Yale University and a high school in Berkeley in recent weeks.

I take full responsibility for this frustration and I take full responsibility for the inaction that has occurred. Use my resignation to heal and start talking again.

— Tim Wolfe, University of Missouri president

University of California President Janet Napolitano said that college campuses have “historically been places where social issues in the United States are raised and where many voices are heard. That’s just part of a university.”

But the rise of social media had made a major difference, she said, between activism on today’s campuses and those during the Vietnam War and civil rights era of protest. “It makes the pace of things more rapid now,” she said.

In Missouri this year, campus activism was stretched to unusual limits, owing in part to social media, and to many students’ connections to the protests in Ferguson and a desire to bring the fight closer to home.

“A lot of Mizzou students traveled to Ferguson,” and those who didn’t “wanted to stand up and make a change,” said Ayanna Poole, a 22-year-old senior from Tyler, Texas, who is one of the founding members of the black campus activist group Concerned Student 1950. “I do believe it’s been a domino effect.”

The Missouri football team’s strike, announced Saturday and endorsed by Coach Gary Pinkel, risked a loss to the university of $1 million if the team canceled its game next weekend.

Another key factor was graduate student Jonathan Butler, who went on a hunger strike Nov. 2 to demand Wolfe’s removal. Butler, wearing a shirt that said “I love my blackness and yours,” addressed his fellow students at a campus amphitheater Monday.

“Please stop focusing on the fact of the Mizzou hunger strike itself,” Butler pleaded to a quiet audience. Focus instead, he said, on the “disgusting and vile” reasons a hunger strike had been necessary in the first place.

A semester’s worth of increasingly turbulent protest marked one of the most notable recent episodes of activism at the university system’s flagship campus in Columbia. But episodes of racism on campus long preceded Wolfe’s reign.

Cynthia Frisby, a journalism professor, wrote in the Missourian newspaper this week that in her 18 years at the university, “I have been called the N-word too many times to count.”

In 2010, two white students scattered cotton balls on the lawn of the campus’ black culture center in what black students saw as a racist attack. The pair were convicted of littering.

One of the key differences since Wolfe’s arrival as president in 2012 has been the advent of social media as a weapon for activism and racism alike.

University of Missouri students spotted an anonymous threat on the social media app Yik Yak in December, after riots in Ferguson: “Let’s burn down the black culture center & give them a taste of their own medicine.”

Hundreds rallied on campus to protest the message.

In September, the president of the Missouri Student Assn., Payton Head, who is black, said that he was walking through campus when a man in a pickup shouted a racial epithet at him.

Head confronted the issue in a short essay on Facebook.

“I’ve experienced moments like this multiple times at THIS university, making me not feel included here,” Head said in a post that went viral, with other students echoing his account with their own.

Colleges and universities have faced difficulties with the rising use of social media to both document alleged incidents of racism or violence and to organize protests against them, according to Barmak Nassirian, director of policy analysis at the American Assn. of State Colleges and Universities.

“The availability of instant video, photo and texting generally means that a lot of things that might have remained a very local concern quickly take on a national following and national implications,” he said.

That makes what is already a challenging job for a university president “that much more challenging,” Nassirian said. Campus leaders might not realize at first how an incident on campus can suddenly take on much wider implication.

University of Missouri administrators seemed to stumble in response to viral-ready incidents, and each stumble only made Wolfe a greater target.

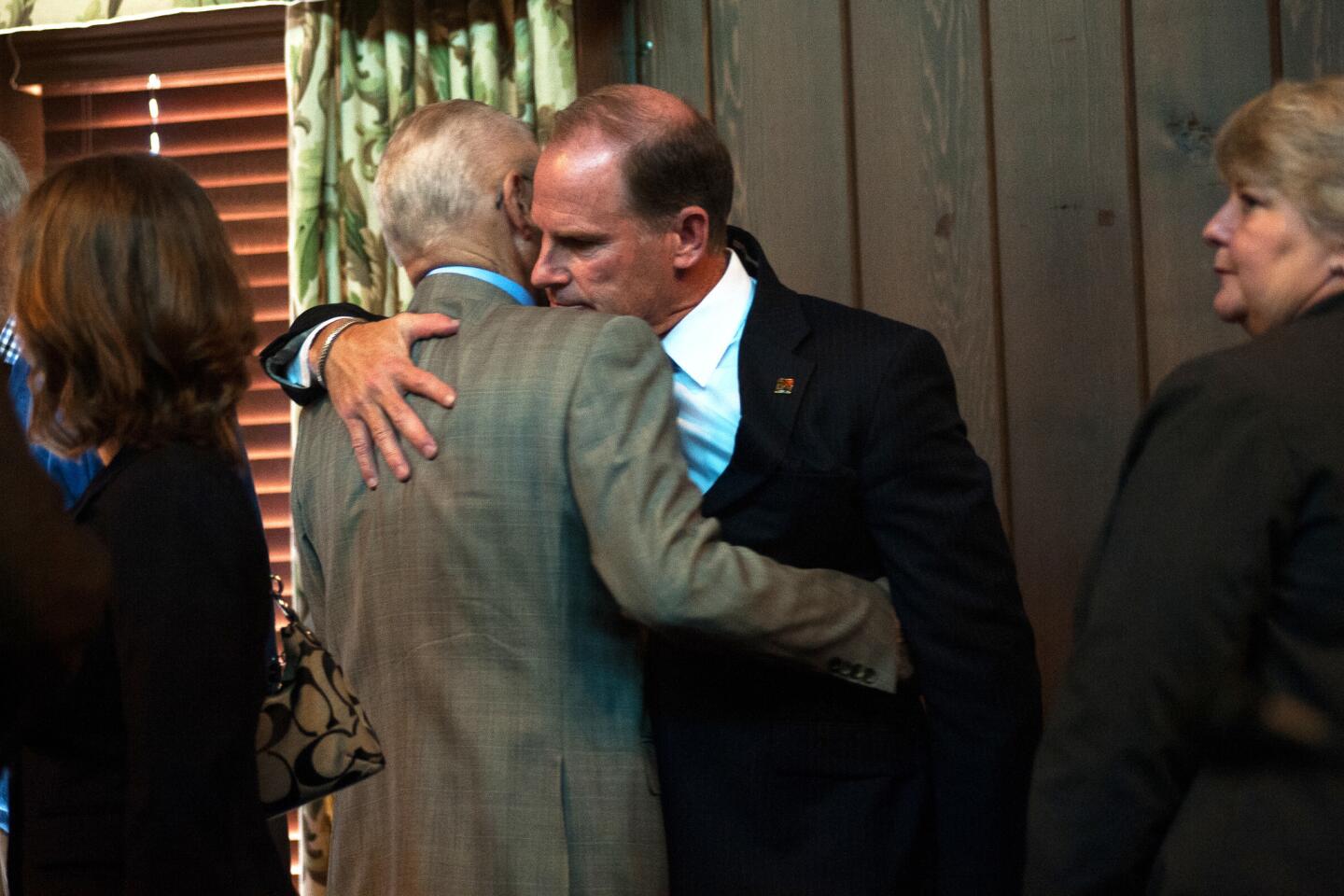

When students asked him to define systematic oppression Friday night outside a fundraiser in Kansas City, Mo., Wolfe replied, “Systematic oppression is because you don’t believe that you have the equal opportunity for success,” upsetting protesters by implying oppression was a perception rather than a reality. The event was captured in a video that, of course, was viewed and shared thousands of times.

When black protesters surrounded his car during a homecoming parade in mid-October, Wolfe sat silent instead of getting out or opening a dialogue.

The homecoming confrontation was the moment Concerned Student 1950 was born, its name an allusion to the first year that the university accepted a black student.

The group empowered itself through Twitter and Facebook, and rejected reporters from other media. A video emerged Monday of protesters arguing with and shoving a freelance student photographer trying to capture celebrations on the public campus quad.

One adult in the video can be seen grabbing a videographer’s camera and telling him, “You need to get out,” and then shouting to other protesters: “Who wants to help me get this reporter out of here? I need some muscle over here!”

“We truly appreciate having our story told, but this movement isn’t for you,” the group tweeted from its Twitter account.

The photographer who was shoved, Tim Tai, responded.

“Wow,” Tai tweeted. “Didn’t mean to become part of the story. Just trying to do my job.”

Twitter: @mattdpearce

Times staff writer Larry Gordon in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

ALSO:

Air Force struggles to add drone pilots and address fatigue and stress

In Vegas area, Bernie Sanders woos Latinos with mariachis and immigrant heritage

‘Tale of two Californias’: Coastal voters upbeat on economy, inland residents anxious

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.