Can Trump put another Justice Scalia on the Supreme Court?

During his campaign, Donald Trump listed potential Supreme Court nominees. Here’s a rundown of how the process will work.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — President-elect Donald Trump will soon have the chance to make good on one of his most consequential campaign promises: fill the Supreme Court vacancy with a judge in the mold of conservative icon Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in February.

Any Trump nominee is almost guaranteed to be a conservative jurist who is anti-abortion and supports the 2nd Amendment’s right to bear arms.

But what kind of conservative he selects will determine whether his first nominee will be quickly confirmed or instead trigger a fierce fight in the closely divided Senate, potentially overshadowing the early months of Trump’s presidency.

If Trump opts for a Scalia-like justice, as he repeatedly said he would during the campaign, conservatives lawyers say the betting favorite is Judge William H. Pryor Jr. from the 11th Circuit Court in Atlanta, a former Alabama attorney general who called the Roe vs. Wade decision legalizing abortion the “worst abomination in the history of constitutional law.”

The 54-year-old Pryor believes in Scalia’s approach of interpreting the Constitution by its “original meaning” — one which has little room for gay rights, even women’s rights. His nomination would electrify Trump’s conservative base, but it would also set off a confirmation battle for which the outcome is not assured.

“His nomination would ignite a firestorm across the country,” said Nan Aron, president of Alliance for Justice, among the liberal activist groups that are already mobilizing to fight a Pryor nomination. “Our organization and others would pull out every stop to keep him off the court.”

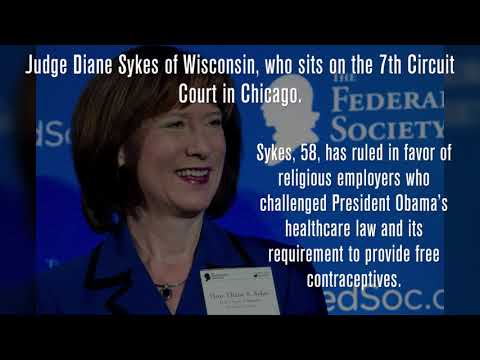

Instead, Trump may opt for a less provocative nominee, such as Judge Diane Sykes of Wisconsin, 58, a moderate conservative who sits on the 7th Circuit Court in Chicago.

Sykes has ruled in favor of religious employers who challenged President Obama’s healthcare law and its requirement to provide free contraceptives, and she voted to uphold Wisconsin’s voter ID law. But she has not taken sharply ideological stands or called for overturning liberal precedents.

Pryor and Sykes have been seen as top contenders ever since Trump mentioned them by name during a Republican debate shortly after Scalia’s sudden death, which threatened to tilt the court’s ideological balance to the left.

But much will depend on the whether the GOP-led Senate moves to alter its filibuster rules.

If the new Senate maintains its current rules, it would take 60 votes to cut off debate and set a final vote on a Supreme Court nominee. That would allow the minority Democrats, voting as a bloc, to prevent confirmation of a controversial pick like Pryor. Republicans next year are expected to control only 52 seats.

But Republican leaders could simply change the rules to clear the way for Trump’s high court nominee to be confirmed with a simple majority. That’s what Democrats did in 2013 when they controlled the Senate and wanted to overcome Republican filibusters against Obama’s judicial nominees. At the time, Democrats exempted Supreme Court nominations from that rule change.

It remains unclear whether Republicans will agree on changing the rules to allow confirmations with just 50 votes. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) has said he would oppose abandoning the filibuster rule, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has also been seen as resistant to changing long-standing Senate practices.

Even so, Pryor appears to have the inside track, according to conservative lawyers and advisors in touch with the transition team.

Before becoming a judge in 2005, Pryor drew attention with a series of outspoken Scalia-like pronouncements on issues like abortion and gay rights.

He ended one speech in 2000 with a prayer for the newly elected George W. Bush, saying “Please, God, no more Souters.” It was a reference to Justice David Souter, a Republican appointee who disappointed conservatives during his 19 years on the court by frequently siding with liberals.

No one on the right worries that Pryor would move to the center or the left if he were appointed to the high court. He is also a protégé of Jeff Sessions, the Alabama senator who is slated to become Trump’s U.S. attorney general.

Last week, the conservative Federalist Society met in Washington, and Pryor was seen by many as the favorite for Trump’s first high court nomination.

“He would be great,” said Roger Pilon, vice president of the libertarian Cato Institute.

Trump appears to share that view. Hours after Scalia died, Trump mentioned Pryor and Sykes as among the “fantastic people” who could replace Scalia.

“I hope that our Senate, Mitch [McConnell] and the entire group, is going to able to do something in terms of delay. We could have a Diane Sykes or a Bill Pryor,” he said, calling upon Senate Republicans to block Obama from filling the seat. The GOP-led Senate pursued such a strategy, refusing to consider since March President Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick Garland.

During the campaign, Trump put out two lists and a total of 21 potential Supreme Court nominees, and his aides say he will make his selection from those lists.

Lawyers at the Heritage Foundation and the Federalist Society expect Trump will choose a federal appeals court judge who is under age 60 and has a conservative record. Other favored candidates include Judges Neil Gorsuch, 49, from the 10th Circuit Court in Denver, Steven Colloton, 53, from the 8th Circuit in St. Louis, and Raymond Kethledge, 49, from the 6th Circuit in Cincinnati and Thomas Hardiman, 51, from the 3rd Circuit in Philadelphia.

Trump’s list also includes several state justices, and the most talked about names are Joan Larsen, 47, a Michigan Supreme Court justice who was once a clerk for Scalia, and Texas Supreme Court Justice Don Willett, 50, an avid tweeter who at times has criticized Trump.

At the Federalist Society meeting last week, panel talks included nine of the 21 potential Trump nominees to the high court. Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas also delivered speeches.

Pryor moderated a panel on the “separation of powers,” and he echoed Scalia’s view that “real constitutional law” is about the “governing structure,” not the individual rights protected by the Constitution. “It’s a mistake to think the Bill of Rights is the most important feature of American democracy,” he said.

Pryor, like Scalia, believes issues such as abortion or same-sex marriage are not individual rights protected by the Constitution, but instead are matters to be decided by the states and their voters.

George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley, who spoke on the panel, said he has known Pryor since they were law clerks in New Orleans.

“Bill is extremely smart and committed to first principles of constitutional interpretation,” Turley said after the panel talk. “He strongly believes in the original design of the ‘dual sovereignty’ between state and federal governments. He believes that states must make the decisions in traditional areas” of responsibility, including abortion, the death penalty and gay rights.

In 2003, when the Supreme Court was hearing a challenge to a Texas law that made gay sex a crime, Pryor filed a friend-of-the-court brief on behalf of Alabama urging the court to rule for Texas. He said the court should not be swayed by “political correctness. … Engaging in homosexual sodomy is not protected” by the 14th Amendment and its reference to liberty, he wrote. Upholding such a claim “must logically extend to activities like prostitution, adultery, necrophilia, bestiality, possession of child pornography and even incest and pedophilia,” he added.

The Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision struck down the Texas law as an unconstitutional invasion of liberty and privacy. In dissent, Scalia wrote a passage similar to Pryor’s brief. The court’s ruling, Scalia said, has “called into question … state laws against bigamy, same-sex marriage, adult incest, prostitution, masturbation, adultery, fornication, bestiality and obscenity.”

Pryor grew up in a Roman Catholic family from Mobile, Ala., graduated from Northeast Louisiana University in Monroe and from the Tulane Law School.

In 1996, Pryor was a 34-year old deputy attorney general in Alabama when Sessions, his boss, was elected to the Senate. He took over as state attorney general and won a narrow election in 1998.

When George W. Bush became president, he picked Pryor for the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, but his nomination ran into fierce resistance from Senate Democrats.

They blocked his confirmation, but Bush went around them and gave him a recess appointment. Then, in a bipartisan deal, the Senate agreed to hold votes on several stalled judges, and Pryor won confirmation on a 53-45 vote in 2005.

On Twitter: DavidGSavage

ALSO:

Supreme Court turns down Ohio Democrats’ bid to restore ‘golden week’ of early voting

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.