Must Reads: The inside story: How police and the FBI found one of the country’s worst serial killers

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — The FBI analysts sat mutely, listening intently to the scratchy audio feed from an interview room across the hall.

The two women were anxious, having spent months collecting and assessing ephemeral crumbs from the nomadic life of Samuel Little, a 77-year-old California prisoner and once-competitive boxer whom they suspected of multiple murders.

They had no hard evidence — no fingerprints, no DNA, no witnesses. Little had been convicted in 2014 of strangling three women in Los Angeles and they were convinced he had killed others. How many, they didn’t know.

The analysts mostly had a gut feeling, informed by detailed research into four decades of Little’s itinerant wanderings across the country. Again and again, in state after state, he seemed to intersect with long-cold investigations into bodies and bones.

Their only hope was to obtain a confession, a task that fell to a Texas detective known for his expertise in sociopaths and psychopaths. But no one was optimistic.

Huddled in a guard break room in the California State Prison in Lancaster on May 17, the analysts shifted uneasily in their seats, their ears locked on a speaker and eyes fixed on a stack of notes, police reports and crime scene photographs spread across a table.

They were as ready as they could be, though nothing could have prepared them for what was to come — the unspooling of one of the nation’s worst serial killing sprees, involving dozens of deaths.

It would take dogged police work and more than a little luck. Unlike investigations that start with a victim and lead to a killer, this time a suspect would have to lead to the corpses. But was Little ready to talk?

California inmate confesses to being a serial killer responsible for about 90 deaths »

***

The extraordinary investigation began in April 2013 when FBI analyst Christie Palazzolo received a call from Los Angeles homicide detectives, according to the FBI analysts, police investigators and a review of court files.

The LAPD detectives wanted to talk about Little. He had been arrested in 2012 at a homeless shelter in Kentucky on a warrant for a narcotics violation in Los Angeles.

Authorities had then linked him to three long-unsolved cases — women who were strangled in Los Angeles in 1987 and 1989. His DNA was found in semen on the shirts of two and skin under the fingernails of the third. The half-naked bodies had been found in an alley, a parking garage and a Dumpster.

Born in 1940 and raised in Ohio, Little had been in and out of trouble for most of his life. He spent about a decade behind bars and had been arrested scores of times on charges ranging from assault and rape to armed robbery and burglary.

He was repeatedly accused of targeting vulnerable women — largely prostitutes, drug addicts, the homeless and others living on the street or on the edge.

He was acquitted of the 1982 killing of a mentally disabled woman in Florida and a grand jury declined to indict him that year in the death of a prostitute in Mississippi. Both cases involved women who were strangled — just like the three in Los Angeles.

Two years later, he was convicted of assaulting two women in San Diego, and spent two years in prison. Evidence showed he had tied one up with stockings in a car and choked her nearly to death.

In old mug shots, Little looked every bit the ex-boxer — muscular, broad-shouldered but trim, with bushy hair and a thick mustache. In a 1972 police photo, when he was 31, Little looked bored, with his head cocked, as if shrugging off his latest arrest.

LAPD detectives found Little an enigma in 2013, however, partly because he refused to speak with them. That’s when they asked Palazzolo to reconstruct his life — maybe she could find clues pointing to other murders.

Palazzolo is one of 10 analysts assigned to the FBI’s Violent Criminal Apprehension Program. Based in northern Virginia, ViCAP maintains a database of homicides and other violent crimes that police can search to help find suspects or put names to unidentified victims.

The analyst, 34, and her colleagues provide hundreds of leads each year to help local-level police resolve so-called cold cases — long-unsolved murders.

Despite Little’s use of aliases — Samuel McDowell was a favorite — Palazzolo was able to comb his criminal history and discover more arrests in other states.

She plowed through commercial databases, finding where he rented an apartment, lived in a hostel or held an odd job, including one at a cemetery.

The analyst next dug into the ViCAP database, looking for unsolved homicides that overlapped with her 150-page timeline of Little’s life. She discovered a handful but suspected he might have committed more.

One stood out: the 1994 strangling of 38-year-old Denise Christie Brothers in Odessa, Texas. Her partially clothed body had been found in bushes in a vacant lot. Records showed Little had interacted with local police around that time, meaning he was in Odessa.

“This just felt like him,” Palazzolo said.

ViCAP transmitted a national alert in June 2013 urging detectives to check their files for unsolved stranglings and other assaults on vulnerable women, and the next year the FBI sent Palazzolo’s final report to the LAPD.

Little was convicted in L.A. County Superior Court in September 2014 of murdering the three Los Angeles women and sentenced to life in prison. Although he appealed, investigators expected him to die in prison, taking his murderous oeuvre to the grave.

***

Just over three years later, in December 2017, Angela Williamson was attending a law enforcement conference in Tampa, Fla.

Armed with a doctorate in molecular biology and extensive experience in forensics, the 41-year-old Australian-born analyst splits her work between ViCAP and a Justice Department program that funds local-level police efforts to better investigate sexual assaults and related homicides.

She was chatting with Texas Ranger James Holland, who had just given a presentation about how to interview sociopaths and psychopaths, when two investigators from a Florida law enforcement agency sidled up.

They asked whether Williamson and Holland knew anything about a guy named Samuel Little. He had strangled three women in Los Angeles and might have killed others in Florida, they said. They wanted Holland’s insights.

The Texas Ranger and FBI analyst promised to look into the suspect.

In March, Holland called Williamson at ViCAP and told her they had to do something “about this Little guy,” she recalled.

Williamson turned in her cubicle and got Palazzolo’s attention. She had a Texas Ranger on the phone and wondered if Palazzolo knew anything about Little.

“You bet I do!” Palazzolo said excitedly. “Tell him about the Odessa case.”

Within weeks, the trio was in Lancaster to interview Little. They brought the Odessa case file, old newspaper clips, Palazzolo’s detailed timeline of Little’s life and other material. He had no idea they were coming — their plan was to surprise him.

“I was pretty pessimistic,” Palazzolo recalled. “I thought he would just tell us to leave. Remember, he hadn’t spoken to anyone about any of this. Why would he?”

Just after 10 a.m. on May 17, Holland sat down with Little and gave him some peanut M&M’s. In his Texas drawl, the ranger began chit-chatting about this and that — Little’s time on the streets, his competitive boxing.

The ranger played to Little’s ego, saying the FBI and Justice Department were very interested in him.

It didn’t work. Little had beat murder raps before, and he insisted he would win his appeal in Los Angeles and soon be free.

Listening on the audio link, Palazzolo and Williamson slumped in their chairs. This was going nowhere.

After 30 minutes or so, Holland brought up the Odessa case. It seemed to flip a switch in the killer’s head, although investigators still aren’t sure why.

Little became animated and suddenly began discussing the 1994 slaying. Better yet, his surprisingly precise recall matched details in the crime scene photographs and reports.

“Game on!” Palazzolo said in the guard break room.

That night and the next, Holland and the analysts convened at the hotel and reviewed the day’s audiotapes. In two days, Little had described 20 slayings in detail.

He had also cataloged his killings: “Jackson, Mississippi— one. Cincinnati, Ohio — one. Phoenix, Arizona — three,” he had told Holland, leaving the analysts to perform the addition.

Yet none of Palazzolo’s suspected cases matched Little’s grim tally. They turned to the ViCAP database but also struck out. It can be an imperfect tool because it relies on local-level police to enter data on their cases.

So Palazzolo tried Google, entering one of the cases into the search engine. She stared in shock at the results.

“I just found one,” she told Williamson. Investigators would later corroborate Little’s confession in that killing. The discovery spurred the team to step up the investigation.

Ultimately, Little confessed to killing 90 women between 1970 and 2005, including the two cases he had beaten in Florida and Mississippi. He admitted to strangling 18 in Los Angeles.

His bloody count, if confirmed, would rank Little among the deadliest serial killers in U.S. history.

***

Police have corroborated at least 36 of Little’s confessions and are vetting others.

“This is not a case of him boasting,” said Kevin Fitzsimmons, the supervisory analyst for ViCAP. “Law enforcement has verified he did these things. It takes a lot of work, but we are doing it.”

Confirming the confessions has been difficult. Most of the victims lived in society’s shadows and few of the killings drew intense police attention or publicity.

Many of the deaths occurred before the advent of DNA testing. Many were attributed to accidents, drug overdoses or exposure — not homicide — because police recovered only bones or a decomposing corpse and didn’t have clear evidence of a crime.

One reason is Little left no telltale stab or gunshot wounds. He said he usually stunned or knocked out his victims with powerful punches before strangling them.

He also did not always sexually assault his victims. In any case, many were prostitutes with multiple partners, so rape kits were of limited utility.

Another complicating factor was Little’s memory.

Investigators say it’s nearly photographic when it comes to his victims, methods and other details. He recited one woman’s last meal — allowing detectives to verify his account by checking autopsy results that listed the contents of her stomach.

But his recall of dates is less solid — he can be off by a decade. And he sometimes can’t name the towns where he stalked and strangled his prey.

“When you spent your life living in your car, things tend to blur,” said Williamson. “You can imagine calling a police department and saying you have a potential homicide that occurred off a dirt road in 1984, or it could be 1974, or 1994. Did they even find the body? If they did, was it just bones?”

***

That was the case in early October in Maryland when Prince George’s County Police Det. Bernie Nelson got a call from a colleague in nearby Washington, D.C., asking whether he had any information about a 1972 homicide.

The D.C. detective told Nelson that a serial killer had claimed he had picked up a woman at Washington’s old Greyhound bus terminal, and had driven down a dirt road and strangled her near an abandoned house.

The D.C. detective had no such homicides in his files but thought police in nearby counties might.

Nelson visited the dusty police file room and found the handwritten homicide ledger from 1972. Near the end, he found a possible match: On Dec. 1, police had recovered the bones of an unidentified white woman off a dirt road.

According to the file, a hunter had discovered the remains near a deserted house about a quarter-mile down a rugged road off a major thoroughfare. The medical examiner suspected the victim, 20 to 25 years old, had been strangled six to 12 months earlier.

Nelson learned Little was arrested on a gun charge at the Washington bus terminal on May 28, 1972. He had been arrested in Florida on a rape charge three weeks earlier, but released from custody. Nelson suspected he had killed the woman during those three weeks.

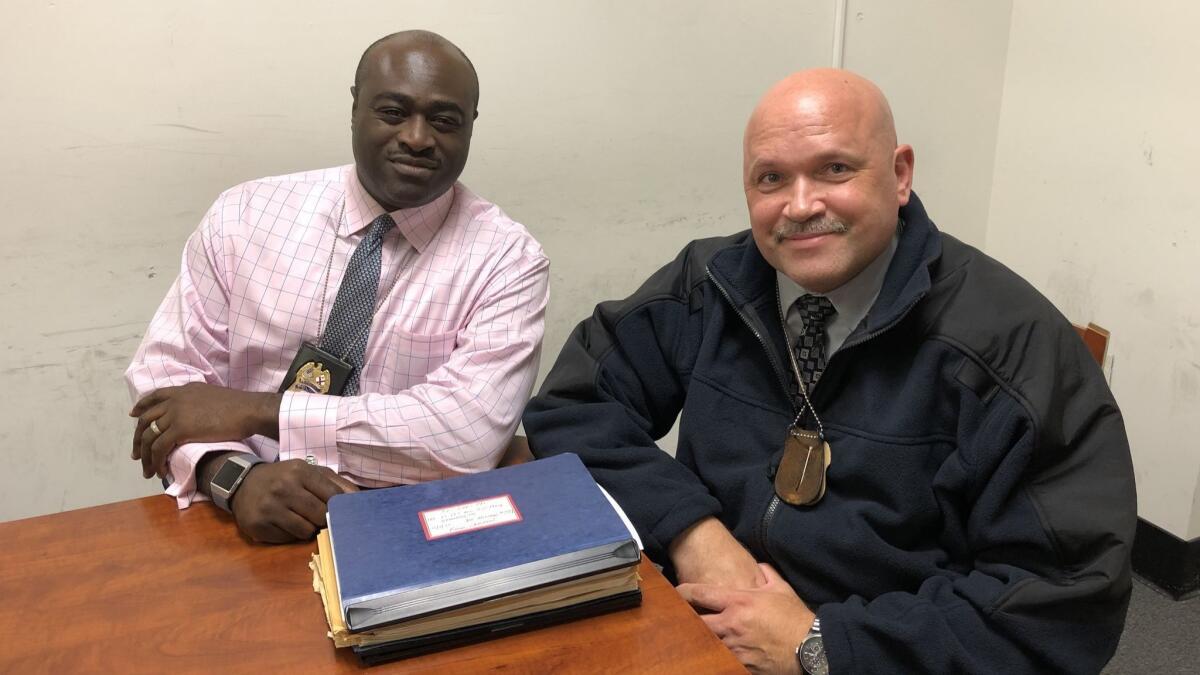

By Nov. 8, Nelson and his boss, Sgt. Greg McDonald, and an FBI agent were in Wise County, Texas, where Little was in jail awaiting trial in the Odessa murder. (On Thursday, he pleaded guilty to that charge. Prosecutors had agreed not to seek the death penalty in exchange for Little’s continued cooperation with the Texas Rangers and FBI.)

In their hotel, they met detectives from four other jurisdictions, also waiting for time to talk to Little.

Before questioning the prisoner the next morning at the sheriff’s office, the visiting detectives were briefed by Holland, the Texas Ranger, and told what to expect.

Little suffered from diabetes and had a pacemaker. He sometimes became sexually excited when he recalled his crimes and would ask to see photographs of his victim to relive the event. The killer could become angry if asked to help a victim’s family find closure.

Little also tended to go off on tangents and would speak of himself in the third person. His memory for faces and the scenes was eerily sharp. He was a decent artist, Holland said, and might be able to render a victim’s likeness.

After Little finished his breakfast from McDonald’s, the Prince George’s County detectives entered the drab interview room and confronted an old man with gray hair in a black-and-white-striped jail uniform. Although he relied on a wheelchair, Little seemed spry.

He boasted of his boxing prowess as a youth and engaged in a bit of a shadowboxing for the investigators. He said he still tried to keep in shape by doing sit-ups and push-ups.

Nelson, knowing other investigators were waiting in line, quickly shifted to the crime.

Little recalled the case, he said. He said he was living out of his car when he met an attractive white woman, a prostitute, at Washington’s bus station, and flirted with her. When she learned he had a beat-up car, an Oldsmobile, she agreed to leave town with him.

She told him she came from Massachusetts and had just been divorced. As she left the bus station, Little recalled, she tossed her purse in the air and screamed, “Wahoo, I’m free!”

Little didn’t remember her name or their destination — perhaps Boston or Baltimore. A few miles outside Washington, he told the detectives, the woman encouraged him to pull off a parkway and onto a dirt road.

As they were having sex, Little was overcome by the urge to kill and began to choke the woman. He thought she was dead but she suddenly awoke and scrambled from the car.

He followed her, put her in a chokehold and forced her to the ground. Little recalled her last words as he choked the life from her: “I’m too young to die.”

His recollection matched perfectly with Nelson’s timeline and crime scene evidence — down to curves in the road and a tree where the bones were recovered.

Prince George’s police expect to charge Little in coming weeks so they can close the case on their books. Prosecutors will not indict Little, Nelson said, because he is already serving life sentences.

Nelson’s goal now is to identify the woman. He has clues — she was from Massachusetts, had extensive dental work by at least two dentists, and had just gotten divorced.

Little has even promised him a sketch of her face.

The killer told Nelson he remembered it well -- down to how her dirty blond hair washed over his hands when he squeezed her neck and how her eyes stared lifelessly into the stars.

Times staff writer James Queally in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

Twitter: @DelWilber

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.