Is this booming Northwest land a paradise or disaster waiting to happen?

- Share via

It was here before anyone made a map and called this corner of it the Pacific Northwest.

“To me,” said David McCloskey, waving an aging hand toward tidelands formed millenniums ago, “it’s an energy field.”

McCloskey, a retired sociology and ecology professor who has spent a lifetime exploring the region’s mountain ranges and waterways, was standing here near the southernmost stretch of Puget Sound. He was trying to explain not just the view in front of him, but all of Cascadia, an elusive realm he helped conceive decades ago that stretches from Northern California to the coast of British Columbia, and deep into the imagination.

The idea of a separate land in the top corner of the country rose and faded over the years, a blend of science, environmentalism and a fuzzy sense of otherness that served as a counterpoint to the ceaseless commercial growth of Seattle, its once-quieter capital. Some called it New Age hokum. Others said it represented a true “Ecotopia,” maybe even a last redoubt against the worst effects of climate change.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

Yet now, as the region booms with newcomers drawn to its technology economy, Cascadia’s distinctiveness has become both indisputably clear and darkly complicated. Its very existence is threatened with what scientists say is a strong likelihood that, sooner or later, it will be faced with the largest earthquake ever recorded in the United States.

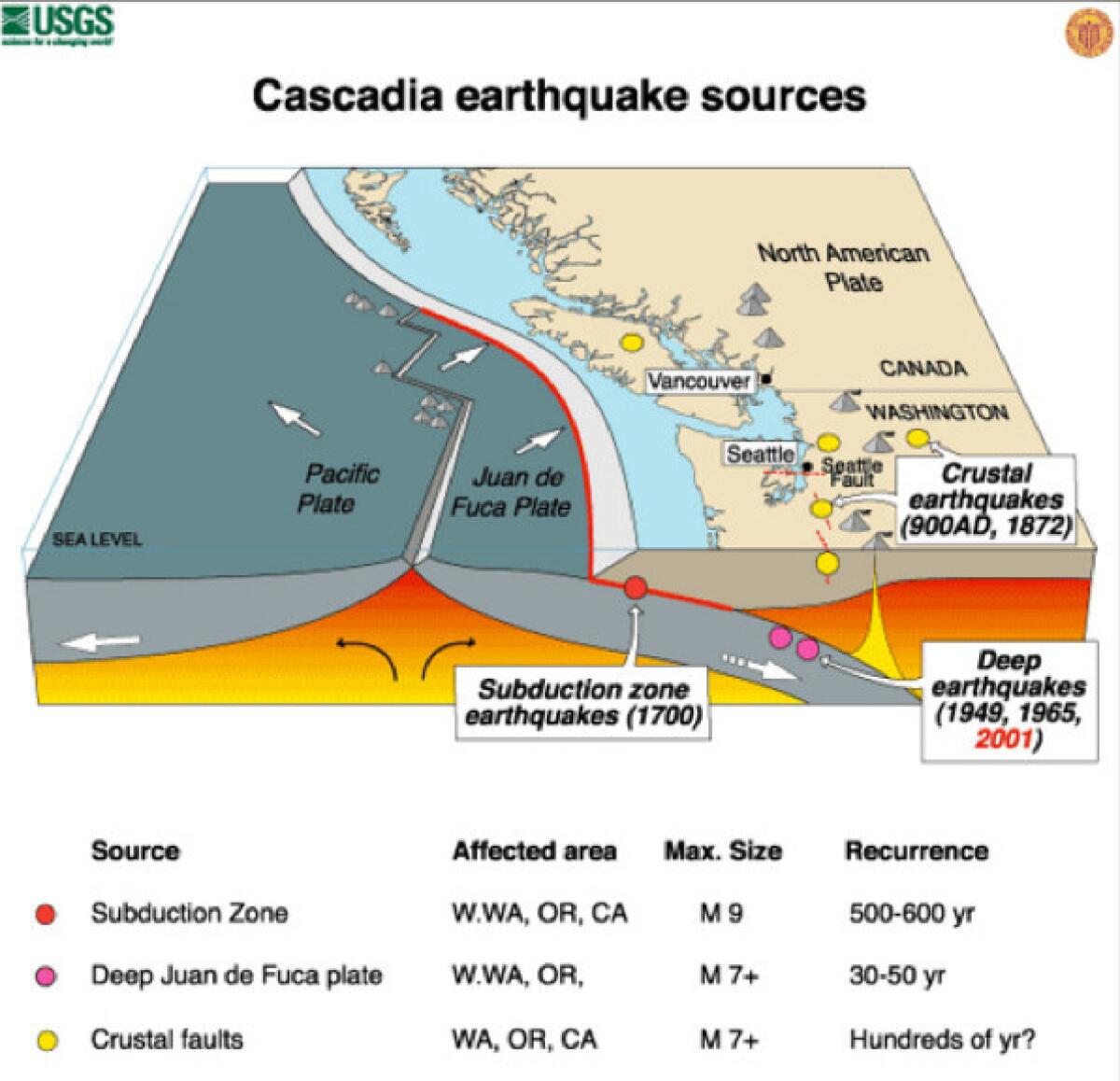

On Tuesday, as many as 20,000 people across Washington, Oregon, California and Idaho, mainly federal employees, will begin a four-day exercise called “Cascadia Rising” — a trial run at responding to a massive magnitude 9.0 quake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone off the northwest coast near here, and the tsunami that would inevitably accompany it.

Scientists have established that the fault in the Cascadia zone caused a megaquake in 1700, before the region’s written history, and they say one day — maybe next week, maybe next century — it will cause another. The death toll could reach 10,000 and leave much of the region without power, clean water or essential services.

Forty years ago, when McCloskey began teaching at Seattle University, plate tectonics were just beginning to be understood. Now the Juan de Fuca plate, just off the coast, has become a rising geologic star — or perhaps a sinking one. Seismologists say the plate is slowly creeping beneath the North American plate, creating the dynamic about which scientists are now so concerned.

Awareness of the potential threat peaked recently with a Pulitzer Prize-winning article in the New Yorker magazine, published last year, that described a worst-case scenario in vivid detail.

The increased attention has made clear that, while the Northwest may feel like a haven from much of the country’s other environmental woes – it could be a comfortable destination for people fleeing hotter, drier parts of the West as a result of climate change, for example – it is on very shaky ground.

“It’s earthquake season every single day of the year,” said Kenneth Murphy, the head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Northwest operations.

Rebekah Paci-Green, who was born and raised in the Seattle suburbs, said that after the New Yorker article was published, “I had ... friends writing me and saying ‘Is this really a good idea for you to live there?”

Paci-Green, 41, understands the risks as well as anyone. She is the director of the Resilience Institute at Western Washington University in Bellingham and the lead author of a document that outlines the scenario on which emergency workers will base their exercise next week. She called it “a pretty extreme look at a pretty extreme event.”

Odds are high that whatever megaquake does strike will not have such severe consequences as the worst predictions, Paci-Green said.

A megaquake will not be “Hollywood-style catastrophic in the Puget Sound,” she said, though she is careful to add: “It’s really important for emergency managers to be planning for a worst-case scenario.”

NEWSLETTER: Get the day's top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

For those wondering whether Cascadia means an ideal place to live, or a potential disaster zone, she says: “You have to have risk and benefit in focus at the same time.”

That aligns very much with what McCloskey says.

While he is unhappy that, for some people, Cascadia has suddenly become shorthand for death and destruction, McCloskey welcomes having more people recognize the power of the “energy field” of Cascadia.

“This is part of the long process of getting grounded here in the ongoing life of the wider, deeper place,” he wrote in an email.

That picked up on a point he made back at Nisqually Reach, where he had traveled as part of a research trip to better understand the glacial forces that shaped the region.

“It’s always about getting grounded in the backyard, where you are, all the way up to the planet and back,” he said. “The integral life of the place as a whole on all of these levels, in depth, unfolding through time, including culture, that’s what we’re after. That’s what gives us a new story.”

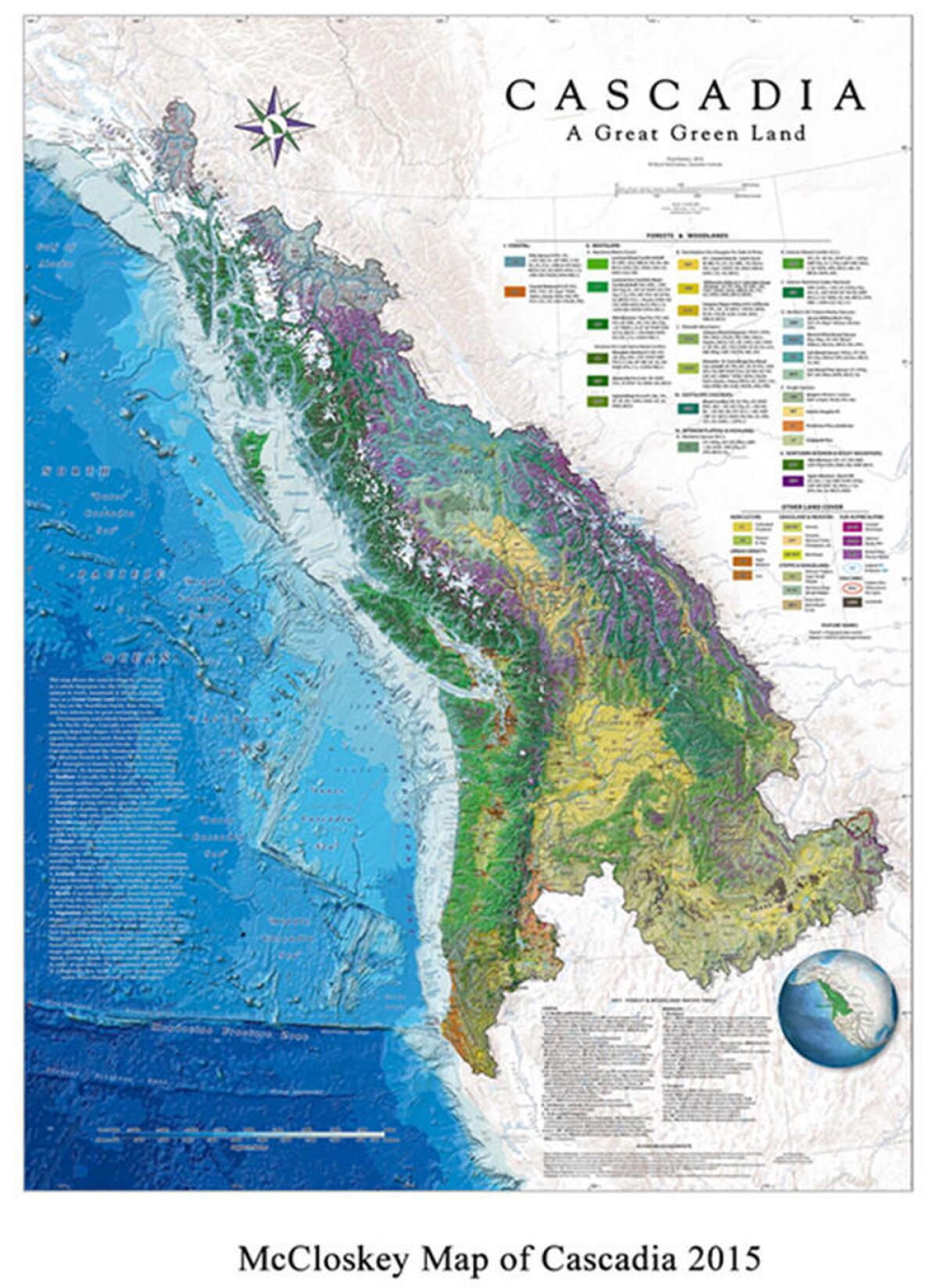

Last year, McCloskey, who is 69, fulfilled a longtime goal to complete a detailed map of the region he loves.

Titled “Cascadia, A Great Green Land” and drafted with the help of a private mapping company, it employs sophisticated cartographic technologies that document features ranging from the Juan de Fuca plate to the ice fields that helped form the mountains and sound and the evergreens that still blanket much of it.

He has also helped create an annual Cascadia Day. Working with the group Cascadia Now, which was formed to carry on his vision, McCloskey chose May 18 for the day of celebration because that is the date Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980. The group calls it “a visceral reminder of the dynamism of our region.”

The main event in Seattle, which included food and bands playing deep into the night, was held in an out-of-the-way warehouse in the shadow of Interstate 5, just south of downtown. As traffic roared overhead, Andrew Nichols and Tanner Colvin sipped craft beer while they sold patches, flags and other memorabilia bearing the Cascadia flag – blue, white and green stripes behind a single Douglas fir tree.

Colvin, 24, is from Montana, “the eastern fringe” of Cascadia, as he put it.

“I have a fascination with regionality,” he said, “with a sense of community beyond borders.”

Nichols, 26, agreed.

“It transcends petty differences like gender or race or politics,” he said. “It’s a culture that is bred out of the environment we grew up in, but everyone who wants to call it home can call it home.”

But what about the Big One, the megaquake. How did that fit into the vision?

“Nature is spectacular and magnificent here,” Nichols said, “but it can also turn on you.”

Colvin leaned in.

“And I’m cool with that,” he said. “We’re basically unified by what can destroy us.”

ALSO

What are the odds of dying in an earthquake?

Watch what 'The Big One' on the San Andreas fault would feel like

San Andreas fault 'locked, loaded and ready to roll' with big earthquake, expert says

Follow William Yardley on Twitter

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.