Portland unnerved by discovery of high lead levels in school drinking water

- Share via

Reporting from Seattle — Communities across the U.S. have been testing their water in the wake of a lead contamination crisis in Flint, Mich., and for the most part, the results have seemed reassuring, with many cities declaring their water safe to drink.

One exception has been a city that has always prided itself on its natural stream-fed drinking water: Portland, Ore., recently discovered high levels of lead in its school drinking water, and the agonizing drip-drip-drip of additional revelations that has ensued has left the Rose City with a toxic hangover.

Public records, including newly released emails, have revealed that school officials not only knew the water was unsafe, but allowed students and teachers to drink it while officials decided on a course of action. The district also failed to disclose all it knew, and the schools’ health officer was found to have misled the public.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The two-week-old controversy has already produced a campaign to dump schools Supt. Carole Smith.

“They knew about the lead,” says one school parent, Mike Southern, who is pushing for a criminal investigation of district actions and has started an online petition to oust Smith. “They did nothing.”

Smith, superintendent of the 49,000-student district since 2007, apologized last week and took responsibility for the delay in notifying students and parents about unsafe lead levels.

“This gap in information and communications regarding health and safety cannot happen again,” she said in a statement, “and I am working to ensure that it won’t.”

Portland isn’t alone. While cities, especially those in the West, have generally shown favorable test results for municipal drinking water, school water systems — often older piping systems — are facing bigger problems.

A recent USA Today analysis of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data found almost 350 schools and day-care centers failed lead tests 470 times from 2012 through 2015. All tested above the EPA’s lead “action level” of 15 parts per billion. One Maine elementary school came in 41 times higher.

If the action level for lead is exceeded, the EPA says, extra measures must be taken to control corrosion. Children are at particular risk for lead exposure to their central nervous system and have “no safe blood lead level,” the agency says. Exposure can result in reduced IQ and attention spans, learning disabilities, hyperactivity, behavioral problems and impaired growth.

The Portland lead test results, released at the end of May, surprised and then angered some parents when they learned the results had been known since March 31. Smith was aware of the March testing but says she didn’t learn of the results until late May.

The test results from Creston and Rose City Park elementary schools showed lead levels as high as 33 parts per billion. Retesting a month later at Creston turned up a 53 parts per billion reading, three times the action level.

Creston’s principal and some Parent Teacher Assn. members received the results on May 16, but no action was immediately undertaken. The superintendent’s office received the results May 25.

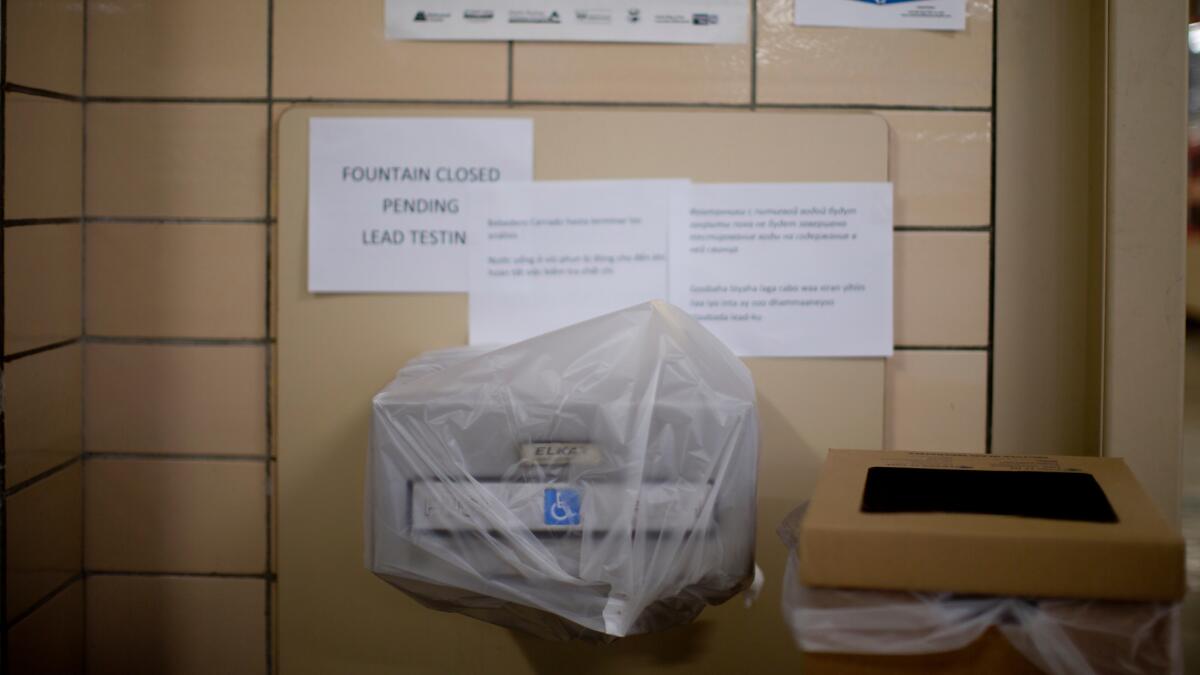

All district drinking fountains were finally shut down May 27, and students were given bottled water as replacements. Smith announced she was bringing in a local law firm to review the district’s internal response to the crisis.

The PTA was at the forefront of uncovering and responding to the dilemma. The Creston PTA sought the initial testing and, after the results became known within the district, PTA President Lisa Kensel learned Creston officials had taken no action. On May 24, she posted her own signs at the school, warning students not to drink the water.

Last week, the district reported the tests results from two Rose City Park elementary students revealed blood lead levels “that fell within the range recommended to see a doctor” for more testing. No connection to the school lead levels has yet been made.

Using record requests to dig deeper, Willamette Week revealed that high lead levels were found at over half of 90 school sites tested between 2010 and 2012, while the Oregonian reported the district hadn’t done regular, comprehensive drinking water testing in 15 years.

That was despite a 2001 determination that “most schools have at least one location where lead levels are above 15 [parts per billion],” according to then-Supt. Jim Scherzinger.

Last week, the release of district emails threw the swiveling spotlight on the district’s senior manager for environmental health and safety, Andy Fridley, who had participated in the initial testing. Critics say his messages to parents and co-workers portray him as misinformed and reluctant to take action.

If contaminants aren’t found in initial testing, he wrongly told one parent, “there is no reason to believe they will be in the future.” District spot testing, he also inaccurately said, had detected only “lead levels at or below” the action zone.

Appointed by Smith two years ago, Fridley was put on paid leave by Smith last week, along with Fridley’s boss, Chief Operating Officer Tony Magliano. Smith says she’s unsatisfied with their handling of the tests.

On Thursday, the district sent a notice to school families and staff, updating ongoing lead testing. “Congratulations,” it began, “on the completion of another school year.”

Anderson is a special correspondent.

MORE NATIONAL NEWS

‘An act of terror and an act of hate’: The aftermath of America’s worst mass shooting

Victims of the Orlando nightclub massacre: Who they were

A hangar at JFK became the tomb of 9/11. Now nearly empty, its job is done

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.