Remarkable dinosaur discoveries under threat with Trump plan to shrink national monument in Utah, scientists say

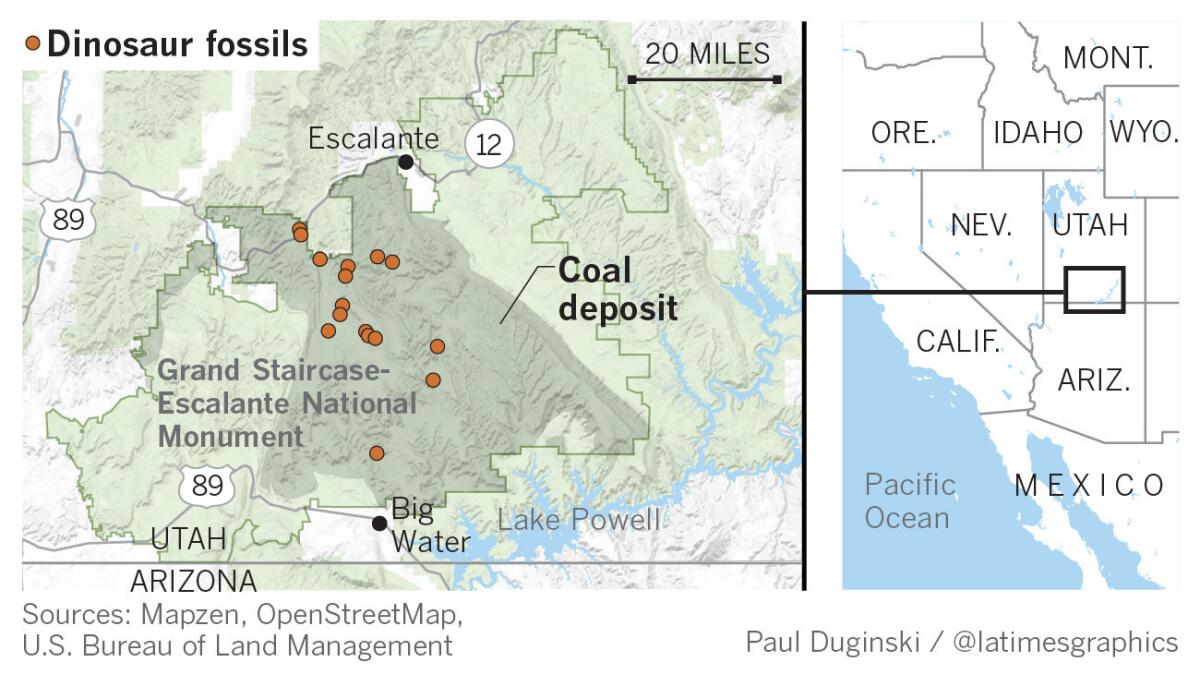

President Trump’s plan to shrink Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah puts one of the planet’s top dinosaur fossil sites at risk, scientists say.

- Share via

The creature looked like a three-ton rhino crossed with a tropical lizard. Ten little horns dangled over its giant forehead like frills on a jester’s cap and two more perched over the eyes. Spikes poked out of each cheek. A blade jutted from its nose.

Paleontologists suspect this freakish beast, named kosmoceratops, was brightly colored to attract mates. It prowled the coastal swamps of southern Utah 79 million years ago.

It is one of more than two dozen new species of dinosaurs discovered in Grand Staircase-Escalante in the 21 years since President Clinton preserved it as a national monument.

The bounty has stunned scientists. Most of this 1.9 million acres of desert wilderness, one of the world’s richest fossil sites for studying the age of dinosaurs, remains unexplored.

But scientists now fear

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, ordered by Trump to reassess the biggest national monuments named since 1996, has proposed shrinking Grand Staircase-Escalante. Whatever area is removed would be open to coal mining, oil drilling and mineral extraction. On Friday, Trump informed Utah Sen.

The fossil beds here are scattered across land that also holds an estimated 62 billion tons of coal.

“My fear is that opening up the monument to energy extraction will threaten our ability to uncover the secrets that we know must still be buried in the monument,” said Scott Sampson, a Canadian paleontologist who oversaw much of the early dinosaur research in the monument.

Trump, who has vowed to revive the coal industry, is tapping into Utah’s longstanding resentment of federal control of public lands. The state’s Republican leaders support Zinke’s recommendation. They were furious at Clinton for creating the monument, which killed a proposed coal mine.

Today’s poor market for coal casts doubt on prospects for mining any time soon. No specific proposal has emerged publicly.

Regardless, environmental groups are preparing lawsuits to thwart any attempt to curb protections of Grand Staircase-Escalante and nine other monuments, as Zinke proposed in August in a report to Trump. Hatch said Friday that Trump has also decided to shrink the size of Utah's Bears Ears National Monument. Specific boundary changes were not immediately released for either monument.

Grand Staircase-Escalante is surrounded by some of the West’s most scenic national parks: Bryce, Zion, the Grand Canyon and Capitol Reef. Its dazzling red-rock cliffs, stone arches and slot canyons are popular with hikers.

What sets Grand Staircase-Escalante apart is the explosion of scientific discoveries.

Beyond kosmoceratops and the other dinosaurs found here, scientists have dug up remnants of extinct forms of crocodiles, turtles, lizards, frogs and birds, along with subtropical flora long gone from Utah’s arid badlands.

A clear window has opened on an entire ecosystem of the Late Cretaceous period, from 100 million to 66 million years ago, when dinosaurs went extinct.

The discoveries are raising more and more questions for scientists, most notably about global warming. How did diverse sorts of life survive in an era when the climate was much hotter, the air contained a lot more carbon dioxide and sea level was extremely high?

“The research in the monument, from my perspective, has only just begun,” said Jeff Eaton, a paleontologist who lives in Tropic, just outside the monument. “The shrinking of it for what I would say are fairly petty, shallow and short-term interests will clearly interfere with, and even potentially destroy, aspects of future research.”

When he signed an executive order mandating Zinke’s review, Trump accused his predecessors of abusing their power to preserve public lands. Presidents can designate national monuments unilaterally; creation of a national park requires an act of Congress.

Press aides for Trump and Zinke declined to comment.

Most of Grand Staircase-Escalante is hard to reach. It’s accessible only by dirt roads and punishing treks by foot across dry woodlands with few trails.

The heart of the monument is the 1 million-acre Kaiparowits Plateau, where fossil beds and coal seams abound. The coal is a vestige of dense greenery in swamps where dinosaurs scavenged for food.

Over the last two decades, the Kaiparowits has become a scientific wonderland, with clusters of geologists, archaeologists, botanists and paleontologists setting up camp for weeks at a time to forage in the dirt.

The paleontologist choreographing their work is Alan Titus, who in his spare time plays electric guitar in a rock band called Mesozoic. As an Interior Department employee, he assiduously avoids talk about the monument’s fate, but his exuberance on the topic of dinosaurs is boundless.

On a recent outing, Titus, 53, hiked briskly past gnarled junipers and pinyons to a spot deep in the desert wilderness where two years ago he discovered a rare tyrannosaur skeleton. The giant reptile’s teeth, the size of rifle bullets, have retained their sharp serrated edge. Titus believes it was killed in a violent storm 75 million years ago.

“It wound up in the middle of a river channel and got buried by sand,” he said as fellow excavators chiseled the animal’s skull out of a stone slab.

The group’s campsite was a few miles away. Tents were spread across the landscape near a fire pit where the half-dozen paleontologists and museum volunteers gather at dinner. Scorpions and snakes are a nuisance, but the tranquillity of the deep wilds is mostly a pleasure. On dark nights, millions of stars offer a breathtaking spectacle.

One of the paleontologists, Scott Richardson, discovered Kosmoceratops richardsoni, the dinosaur’s formal name. Another dinosaur first unearthed in the monument, Nasutoceratops titusi, is named after Titus as a tribute to his pioneering work here.

What Titus calls a “perfect storm” of geological circumstances made Grand Staircase-Escalante a unique treasure.

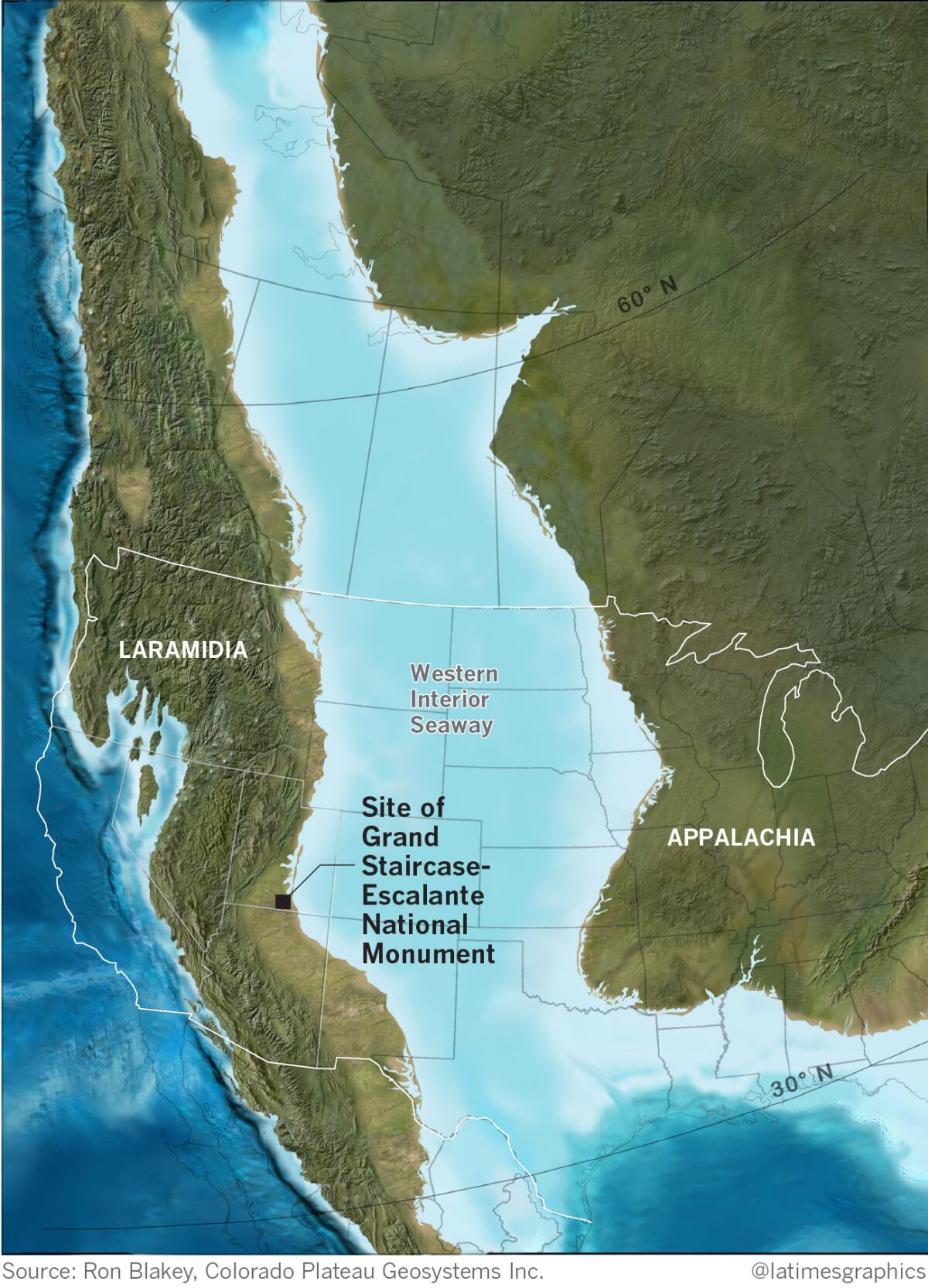

Rising seas flooded North America’s entire Great Plains in the Late Cretaceous. The continent was split in two by the Western Interior Seaway, running between the Arctic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Utah was on the east coast of Laramidia, the narrow western continent. Frequent violent storms washed huge volumes of sediment into the seaway, scientists say.

Dead animals were quickly covered by sand, dirt and gravel that preserved the remains under what eventually became a few thousand feet of earth. They have resurfaced after tens of millions of years of erosion.

“The volume of bone in the Kaiparowits is staggering,” Titus said before reaching for a shard of ancient turtle shell.

The bands of scientists competing for breakthroughs on the plateau reminds Titus of the American explorer Roy Chapman Andrews riding into the Gobi Desert of Mongolia in the 1920s on expeditions that uncovered new species of dinosaurs.

“For the scientist, there’s no greater thrill than to get out and find things that you know are going to push the boundaries of human knowledge,” he said.

Many of the big finds have ended up at the Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City. Visitors can run their fingertips across sandstone rocks with pristine textured impressions of the scaly skin of duck-billed dinosaurs dug up on the Kaiparowits.

“Pretty much every skeleton you see behind me is a discovery made in Grand Staircase since the monument was created,” said Randall Irmis, the museum’s curator of paleontology, referring to kosmoceratops and seven other new species of dinosaurs.

In the far-flung hamlets around Grand Staircase-Escalante, public opinion on the monument is split. The region is populated largely by descendants of 19th century Mormon settlers whose fight against federal control of public lands has shaped local culture ever since.

Many residents are unaware of how significant the scientific discoveries are. Regardless, they prefer mining to a national monument.

Live updates from the Trump administration and the rest of Washington »

“We feel like some of our public land was taken away from us,” said cattle rancher Stoney Burningham of Panguitch, Utah, just west of the monument. “We need coal. God put coal on the Earth for a reason.”

Carlon Johnson co-owns a motel, grocery store and gas station next to the monument visitor’s center in Cannonville. As good as the monument has been for business, he too would welcome some mining jobs.

“Yeah, it would infringe on some of the paleontology, but how much?” he said.

With Gov.

Leland Pollock, a Garfield County commissioner, said a lot of it was just rabbit brush and noxious weeds. “Nobody cares about it,” he said.

Still, spending by visitors to the monument has lifted the local economy. During a recent arts festival in the town of Escalante, population 797, Gary Griffin was selling coffee and baked potatoes on his front lawn. He sees no benefit to scaling back the monument in a quest for coal or oil.

“We don’t have to dig it out of the ground anymore,” he said.

A star speaker at the arts festival was geologist and wilderness guide Christa Sadler, author of the book “Where Dinosaurs Roamed: The Lost World of Utah’s Grand Staircase.” Sadler wants the monument kept intact. She also sees irony in talk of extracting fossil fuel from a landscape so rich with lessons about life on a “greenhouse” planet.

“We need to understand where we came from,” she said, “in order to understand where we’re going.”

Twitter: @finneganLAT

ALSO:

Trump plans to shrink two national monuments in Utah, senator says

Trump may strip protections from 10 national monuments

Civil servants charge Trump is sidelining workers with expertise on climate change and environment

UPDATES:

11:55 a.m., Oct. 27: This article was updated with President Trump calling Sen. Orrin Hatch to tell him he had approved the recommendation to cut the size of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears national monuments.

This article was originally published on Oct. 26 at 1:30 p.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.