Hunger striker gives credit to fellow activists fighting racism at University of Missouri

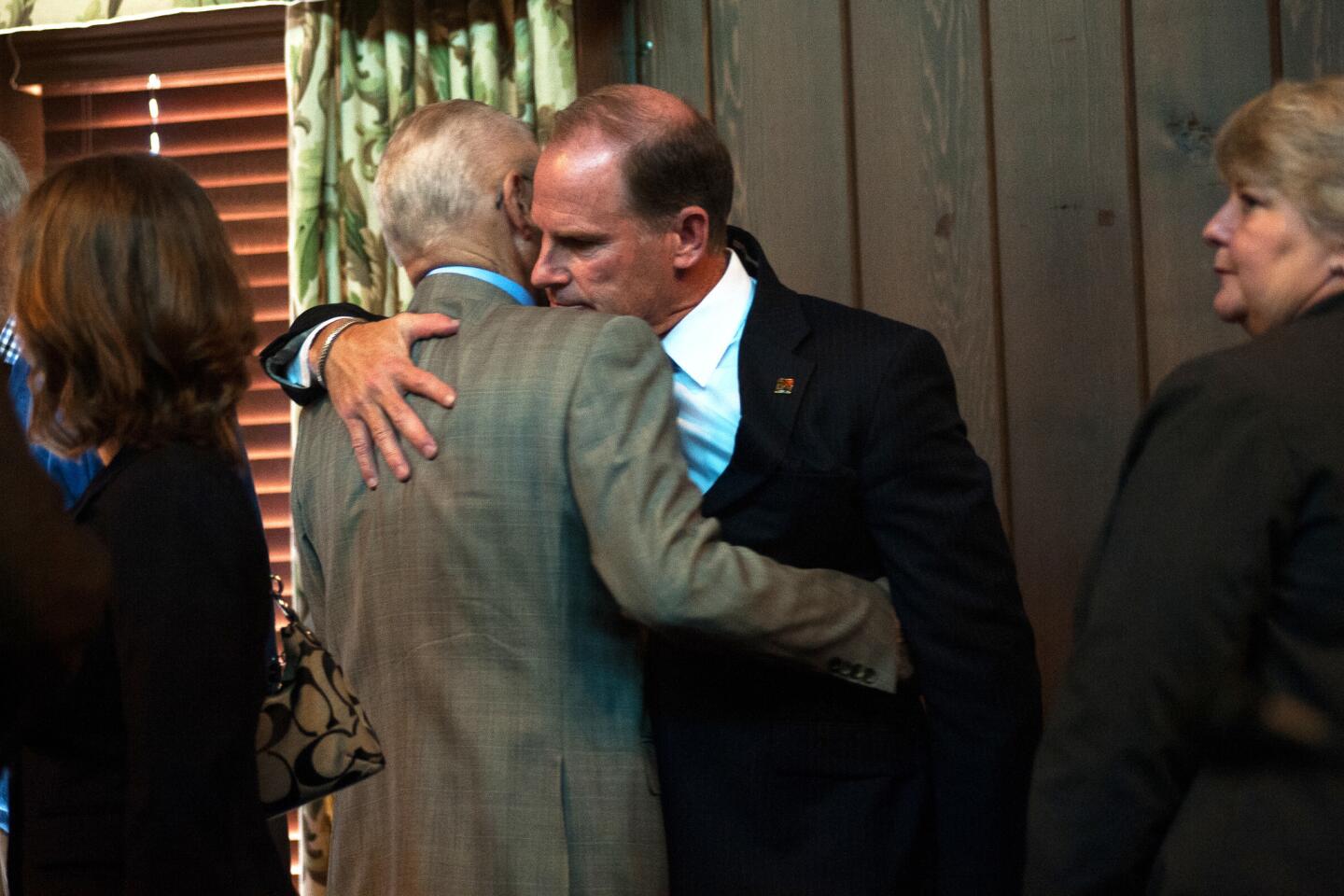

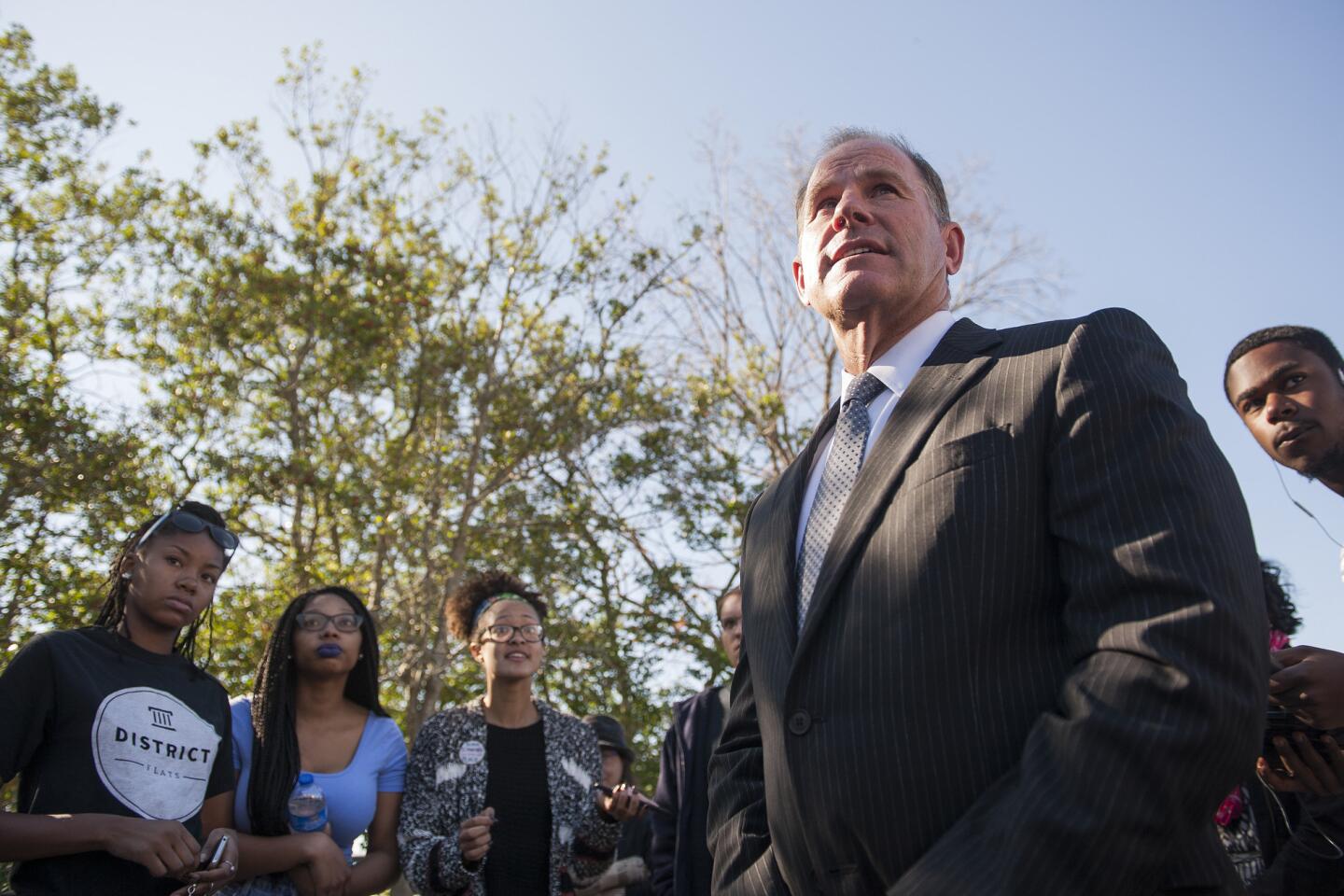

University of Missouri graduate student Jonathan Butler speaks to students Monday after university system President Tim Wolfe announced he would resign. Butler had gone on a hunger strike to force the leader’s ouster.

- Share via

Reporting from COLUMBIA, Mo. — Hauling a laptop in his bag and wearing an expression of tired concentration, Jonathan Butler looked like another graduate student shuffling across the tiled floor of Jesse Hall.

His winter stocking cap and thick-framed glasses might as well be a disguise. Butler is no regular student. On Tuesday morning, Butler, 25, was emerging from a seven-day hunger strike and his central role in the campus drama that upended the University of Missouri this week.

“I feel uncomfortable with the attention,” Butler said as he sat in a chair in the hallway, still waiting to eat his first solid meal since Nov. 2 but now feeling healthier with a temporary liquid diet. “I’m not used to it, and I didn’t do it for the attention. I really just wanted the message to get out.”

For days, students have ringed around him both physically and emotionally — shielding him from strangers and unwelcome journalists like a security detail — seeking to protect him even as he was threatening to starve himself to force the university’s system president to resign.

In the end, Butler won, though he credits the victory to his fellow activists. As the rest of the university woke up Tuesday still figuring out what had happened, he was sitting alone, pondering what comes next.

Butler — who is studying educational leadership and policy analysis — is part of a group of black students who effectively toppled the university’s top administrators, system President Tim Wolfe and Chancellor R. Bowen Loftin, who announced their resignations Monday after an autumn of protests.

For activists, it was about years of racist remarks hurled at black students by people at campus parties and on the streets, and about white administrators’ awkwardness — or silence — in response to protesters’ calls to make a majority-white campus more welcoming to students of color.

The fuse was lit by last year’s protests in Ferguson, Mo., after a white police officer shot an unarmed black 18-year-old. Butler was among the students from the university who made the two-hour drive to the St. Louis suburb to join in.

Butler, an Omaha, Neb., native, said Ferguson was the first time he’d seen black collective action on a mass scale. For a month, he shuttled the 100 miles from campus to Ferguson. “It was monumental in terms of how it influenced me,” Butler said, calling what came next “the post-Ferguson effect.”

Butler began organizing with other students — emphasizing that he was just one player among several — and eventually became one of the 11 students who surrounded Wolfe’s car at the university’s homecoming parade in October. Wolfe didn’t talk to the students as police arrived to force them away.

It was a signature moment. Informally, the students started calling themselves “the brave 11.” Officially, they became founding members of a movement named Concerned Student 1950, a reference to the year the first black student was admitted to the university.

As Wolfe seemed to stumble when confronted by the students’ demands for some kind of decisive response to racial discomfort on campus, he only became a bigger target. Wolfe stopped tweeting. Activists saw him as uncommunicative and confronted him outside a fundraiser in Kansas City.

Butler decided more drastic action was required.

“We did our due diligence,” Butler said. “We wrote letters. We sent emails. We sent tweets. We’ve been to diversity forums. We’ve attended different organizations. We’ve done rallies. We’ve done all the other things, trying to get our voices heard in other formats.… We’ve been doing these things for the past year, year and a half — no response.”

So on Nov. 2, Butler announced he was going on a hunger strike until Wolfe quit.

“It’s not just racism, it’s not just sexism; there’s so many things happening on campus that have to be corrected. We have leadership that’s not competent enough to even empathize with students,” Butler said Tuesday.

Butler didn’t tell his friends about the hunger strike until the night before, on Nov. 1. The next morning, he prayed with friends and ate his last meal, half a waffle.

The hunger strike proved decisive. A tent city immediately began growing on a university quad. The semester-long protests at the university started getting national attention. Then, Saturday night, black players with the university’s football team announced they were going on strike in support of Butler, and the next day, Coach Gary Pinkel and white players announced their support. Butler didn’t even know any football players.

Journalists who flocked to the tent city in response encountered signs on the public quad telling the media to stay out, calling the site a safe space.

Butler said antagonists had stopped by and taunted him by waving candy bars at him and other activists. He said protesters were disturbed by recurring verbal attacks on campus and by journalists who were intruding on intense debates happening inside the tent area.

“We were having some difficult dialogues there, talking about race,” Butler said. “That’s a very sensitive space to be in and be vulnerable in. It was necessary to keep that space very healthy, a very open space for dialogue, versus it being a space where people are going to cover a story, exoticize people who are going through pain and struggle.”

After Wolfe resigned, protesters formed a human shield around the campsite, where celebrations were happening, and chanted for media to stay away, even shoving some photographers who refused to move.

“For me it’s about respect and understanding, that there are other ways to cover this story,” Butler said, noting that journalists should have reported more on the hostile campus climate. “You saying in that moment, ‘That was the only way to cover the story,’ that wasn’t you doing your due diligence.”

The camp late Tuesday began to look a bit disheveled with just a few demonstrators milling around. There were far fewer people than a day earlier when hundreds had gathered.

Concerned Student 1950 changed its stance later Tuesday after a backlash from media and the university’s journalism school professors. The tent camp remains, but activists yanked out their no-media signs and welcomed reporters back with a conciliatory statement.

“TEACHABLE MOMENT,” the group said in paper fliers handed out at the site. “The media is important to tell our story and experiences at Mizzou to the world.... Let’s welcome them and thank them!”

A communications professor caught on video calling for “muscle” to help remove a student photographer from the tent area apologized Tuesday.

“I regret the language and strategies I used, and sincerely apologize to the MU campus community, and journalists at large, for my behavior, and also for the way my actions have shifted attention away from the students’ campaign for justice,” Melissa Click said in a statement released through the University of Missouri College of Arts & Science.

Butler had continued to attend classes through his protests and his hunger strike, reading Bible verses — particularly from 2 Corinthians — for comfort.

But by this week, he was starting to feel sluggish, faint, exhausted, short of breath, sometimes suddenly feeling hot and then suddenly feeling cold. “By day seven, I was really starting to feel it,” Butler said.

After Wolfe resigned Monday, Butler addressed his fellow students on the quad — and then went to the hospital. “Technically, my first meal was my IV,” Butler joked. He declined to go into details about the impact on his health, but he said Tuesday he was doing fine.

Members of Concerned Student 1950 now say they plan to continue their activism, and they’ve called for a meeting with the board of curators and Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon to talk about what happens next.

In a statement, the group has called for “detailed plans to address issues such as minority student enrollment; faculty, staff and administration recruitment; and health resources for students.”

Butler said he wants to focus on pushing the university system’s board of curators to give “shared governance” to students, teachers and staff at the system’s universities — allowing them to have more input into big hiring and operational decisions.

“The whole idea is you can’t have these eight people at the top who are majority white ... making all the decisions,” said Butler, referring to the University of Missouri system’s board of curators. “We should have checks and balances in place.”

He plans to graduate in May and, after that, will look for a job or maybe start on a doctorate.

“Right now I don’t seek a national spotlight,” Butler said, when asked if he wanted to expand his political reach. “It’s not something I’m desiring at all, because I want to stay close to my community, I want to stay close to my people. Right now, my community and my people are students here at the university.”

Twitter: @mattdpearce

MORE ON THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI:

Video captures Missouri protesters’ clash with media

How college football helped bring down Missouri’s president

Missouri protests echo similar situation at UCLA in 1998, but with a bad outcome for football team

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.