‘Go back to where you came from’: Our readers recall racist taunts from their lives

- Share via

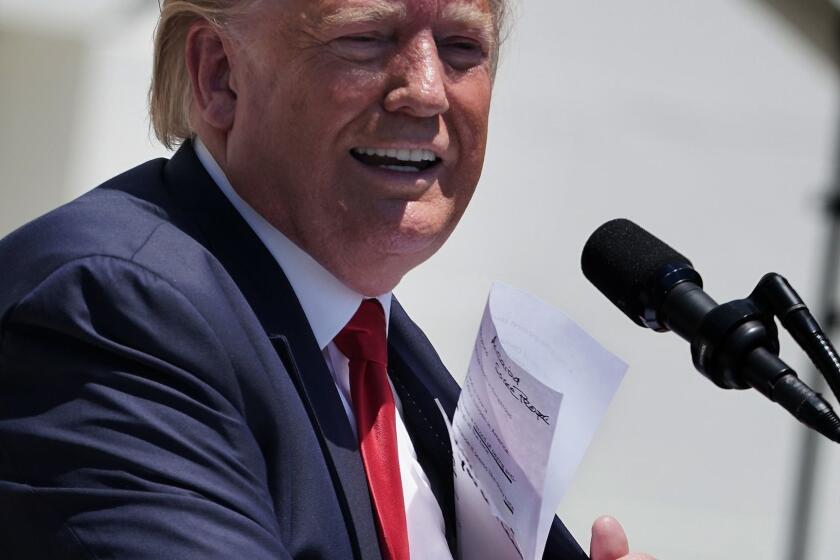

After President Trump’s racist tweets attacking four congresswomen of color, telling them to “go back” to the “places from which they came,” we asked our readers if they had ever been told to “go back” to another country.

Some of the readers who responded were born in the United States; some were not. Some were third-generation citizens; others were waiting to be naturalized. What they shared was the hurt and discomfort that come from the suggestion that they do not belong in America.

Many wrote about how, along with being told to leave the country, they have been on the receiving end of racial slurs and derogatory comments about their name or appearance. And regardless of when it happened, they say the insults stung for years.

We received dozens of responses, and a selection are shown below. To everyone who responded, we thank you for having the courage to share your story.

Moon Alam, Los Angeles

“My senior year of high school in 2001, right after the 9/11 tragedy. I was on my way to work in downtown Los Angeles, waiting for the Dash bus. I had my backpack, and I heard a standard shout: ‘Get her, check her backpack, she probably has a bomb. She is one of them. Go back to where you came from.’

“I don’t think I have ever felt so degraded in my life. I was so afraid. Me, a 17-year-old, among 10 to 15 grown adults, but not one single person spoke up.”

I had just published a story on Sikhs who’d been attacked after being mistaken for Muslims, when the email popped into my inbox.

Richard Samuel Paz, Encino

“About a month ago, I was entering a CVS pharmacy to pick up my monthly medicine…. I am a native of Los Angeles who grew up near Dodger Stadium, 76 years old, and a dark-skinned Latino. I was concluding a conversation in Spanish on my cellphone, when an older white man blurted out, ‘Speak English, you’re in America.’

“I put down my phone and was shocked, but smiled at him and said, ‘I love speaking Spanish, and when I was in the Navy, I spoke Japanese, and Tagalog too.’ He walked past me and retorted, ‘You don’t belong here, this is America.’ I saw two folks who looked like sisters looking at me as I proceeded to the pharmacy shaking their heads, and I was unsure if their gestures were signs of indignation or pity towards me.

“I have always lived in Los Angeles in integrated communities and recently moved into Encino. I was shaken by this insult and later felt angry and questioned myself for not being more aggressive in my response.”

On a good day, I’m almost fluent in Chinese.

Marcus Richardson, Illinois

“In a conversation years ago at my job, I stated that the American dream has yet to extend to every American, especially those of color. My boss told me, ‘If you don’t like it, leave.’ My co-workers all sided with him, adding that I could ‘go back to Africa.’ My parents are from Memphis and I was born in California. I was the only black guy on the crew. This was over 30 years ago and the way they turned on me haunts me still.”

Amaad Rivera, Springfield, Mass.

“I remember how often I heard it in college after 9/11, [when even] fellow students who knew I was born and raised in Massachusetts called me a ‘terrorist.’ While that was a tough experience, my most poignant memory of being told to ‘go back to my country’ was when I was running for city council in my hometown of Springfield, Mass.

“I was knocking on doors during the campaign and was speaking to a voter. He listened to me politely, then told me he would never vote for someone with the last name ‘Rivera,’ as he doesn’t support immigrants. I explained that I was half black and Puerto Rican, and went to school with his son, in this community. He replied that ‘I should go back to my country and run for office’ and slammed the door.

“It made me feel foreign even in the community I grew up in, and that I had no control who decided that.

“That wasn’t the last time I heard that, it was the first time I was unprepared. It still saddens me to this day, and it was 10 years ago.”

The resolution House Democrats plan to pass condemning President Trump for his xenophobic, offensive tweets over the weekend is just that — a resolution, without consequences or punishment.

Rio, Spokane, Wash.

“I was told to “go back where you came from” when I was in the fifth grade, by a group of my classmates, all of whom were white. I was born in the same hospital as many of those white kids were, and I didn’t speak Spanish because my parents were afraid of the harassment I might receive for speaking their native language. My family had successfully assimilated at the expense of their culture, and still it wasn’t enough for my white peers to see me as someone that belonged.”

Frank S. Blair, San Francisco Bay Area

“My wife and I had just moved into majority white neighborhood in the Bay Area when one day we were accosted by a white woman that asked us what we were doing in this neighborhood. Both my wife and I are of mixed race and we were taken back by her odd question. When I asked her, ‘Why would you even ask a question like that?’ she told me, ‘You guys belong on the other side of the tracks. Why don’t you just go back to where you came from?’”

Elleen Pan, Atlanta

“ ‘Go back to where you came from’ and all its variants are words people of color hear and swallow all the time. It’s hard to pinpoint a specific time because the sting of alienation never subsides. It stung when I was a kid on vacation and innocently thought, ‘why does he want us to go back to California?’ And in middle school, when a bully doubly abused stereotypes and told me I was the dumbest Asian he had ever met. Even last year, when I confronted a man who cut me in line and he mocked, ‘Hey, the chink speaks English.’ It’s always a confusing feeling trying to control my anger while justifying their remarks being a result of internalized racism — I was always taught to ignore these comments. I’m a stranger in my own home, feeling smaller and smaller every time my belonging is somehow diminished by the crass insults of people who are no more American than I am.”

David S. Frazier, Ventura County

“The first time I was made to feel less than ‘normal’ was when I was a child of 8. We walked into a drug store in Ventura, Calif. I went straight to the comic books and my mom to the lipsticks. ‘You going to buy?’ questioned an old lady with blue hair. ‘Huh, maybe’ my mom replied to which the old woman said, ‘You and your dirty little Mexican get out my store and go back where you came from.’ I looked down immediately to see if I was ‘dirty’. My mom, flustered, took us out. ‘Mom, why did she say I was dirty?’ My innocence was shattered that day. I did feel dirty, even though I wasn’t. Recently a woman at the local transportation center verbally assaulted me with ‘F— Mexican, go back to Mexico.’ I turned around to see who she was addressing. It was me. I felt very sad that day. This was Trump, I thought. I know I’m brown but I always believed in being judged by my character not the color of my skin.”

Ami Mistry, Canton, Mich.

“During Operation Desert Storm in 1991, I was subjected to all kinds of racial slurs. I was told to ‘Go back to your country, Iraq!’ I am a second-generation Indian American. My parents were both citizens. I told them that I’m not even from Iraq, I’m from India originally. They had a blank look on their face, paused for a second then said ‘same thing! It’s all one country’. Racism is everywhere, I learned that lesson early in life.”

Emmanuel Mauleón, New York City

“I was in a bar in northeast Minneapolis, visiting a friend during my winter break from law school. The declaration to ‘go back’ was preceded by another familiar question, ‘Where are you from?’ A sort of dipping of the first toe to test the waters of racism. ‘I grew up here,’ I responded.

“‘But where are you really from?’

“To which I again replied, ‘Here.’

“The man asking the question identified himself as an off-duty police officer. He became more aggressive, and his ‘Where are you really from,’ quickly turned into ‘I know where you’re from,’ which, coincidentally, he did not. ‘Go back to your f— country you Afghanistani,’ he yelled at me. I did not correct him, because I didn’t think he would be any less hostile upon learning that I was born in Mexico. He proceeded to tell me that he could shoot me in the parking lot, and because he was a police officer, no one would even care. The bar was packed, but no one said anything.”

Alessandro Mannone, Venice, Calif.

“It happened when I first moved to the U.S. from Sicily. That’s to say that as long as I kept my mouth shut, no one would know. I was just a child but I still remember the feeling of sadness. It’s like being put into a bubble that isolates you from everyone else no matter how hard you try to fit in. Just reading or hearing that callous statement today brings it all back. But it did motivate me to lose my accent.

“Unfortunately, to this day I feel as if I don’t fit in, I’m just acting. And the irony is I don’t fit in anymore in Sicily either. These days it’s my learned silence that’s off-putting to people. But how can I explain it to someone that hasn’t experienced it? It’s an isolation to the core.”

Paislig, East Coast, U.S.

“I was in high school when I didn’t stand for the pledge of allegiance. At the time I wasn’t very political and I was just absorbed in rushing to finish my homework last second. My teacher called me out on it and took me to the principal’s office.

“The principal gave me a long lecture on how I was disrespecting the troops, my freedom, and his Italian ancestors who came to this country to make it great, and that if I don’t like it here I can go back to where I came from.

“I was born in a small town in North Carolina. My mother is from California and my father is from Massachusetts. My father served in the military. It had everything to do with the color of my skin, if I was white like my mom I doubt he would tell me to go back to Scotland.”

Thomas Nakanishi, Los Angeles

“I’m a fourth-generation Angeleno and Japanese American and have been told to go back to where I came from throughout my life. It hasn’t happened in L.A. in a long time but I would get confused and ask ‘El Sereno?’ and get puzzled looks in response. When it happened on the East Coast, I would still get confused and ask ‘Los Angeles?’ and get puzzled looks. When it happened in Honolulu, I knew they meant the mainland. When it happens in rural America, I get back in my car and drive. For the most part, I laugh and exclaim that my great-grandparents immigrated to the USA in 1903 before walking (running) away.”

Jennifer Attocknie, Lawrence, Kan.

“I was a freshman at an all-Native American college, Haskell Indian Nations University, but at the time it was called Haskell Indian Junior College. I had moved to a Midwest town, Lawrence, Kan., to attend in 1989.… I was sitting with a bunch of fellow Haskell students [and] a car full of white guys drove up to us and threw beer cans at us and told us to ‘go home.’ They were jeering and yelling.

“After they left, it was silent. Then we all started busting out laughing. We were too slow on the response time, but we said things to each other, like, ‘We are home!’ ‘You first!’ I was a little stunned and hurt, but it wasn’t surprising. Mostly I was thinking it was so ironic and how stupid are they? We are from this land! We may have come from tribes all over, but we had at least that in common. My family is from Oklahoma. I am Comanche.”

Daphne Maria, San Francisco

“It was right before the election and I’m walking down a busy street to catch the train. I have my [headphones] in my ears and was just thinking about getting home. Suddenly a normal-looking man in slacks, with glasses and a backpack runs up to me and starts talking to me. I thought he wanted directions. I stop my music and say, ‘Excuse me?’ And he repeats: ‘It’s your fault. The country’s problems are because of people like you. You’re ruining this country. We’ll be better off without you. Go back to where you came from!’ And then he runs off, and I am left there speechless, trying not to cry.

“I was born in East L.A. My great-grandparents migrated from Mexico around 1918. My Nana was the first to be born in the United States. Her brother served in World War II to gain his citizenship. My father’s side is African American. But it’s never enough because I have brown skin.”

Margarita, Amsterdam

“I was born in Moscow and my parents were the last of the wave of Soviet refugees allowed into the country. The USSR let us leave under the exemption for Jews sponsored by someone in Israel ... but they left us illegally stateless. We were given green cards and then attained citizenship.

“I grew up in NYC but when my dad moved us down to Florida and I was the only Russian in the school, I was constantly threatened by kids telling me I’m a ‘commie’ and to ‘go back to Russia.’ This made me resent my heritage and culture and rebel against it for years.”

Elle H., Virginia Beach, Va.

“When I was 13, I attended an art program for gifted students. As one of the few African American girls in the program, I felt I needed to try harder to fit in with my peers. Our class was working on an identity project when a male student suddenly shouted, ‘Go back to Africa!’ from across the classroom. He looked at me with a taunting glimmer in his eyes as I stood in shock and embarrassment. I didn’t know the history behind his sentiment but could tell it was an insult.

“My thoughts moved a mile a minute. I thought: ‘What does that even mean? My family has lived here for hundreds of years.’ Before I could respond, our teacher chided him: ‘Did you really just say, ‘Go back to Africa?’ That was the entirety of her reprimand. The class grew silent.

“Perhaps the teacher thought it was just an immature joke with no need for punishment, but his words had an impact on my burgeoning notion of race and identity. This impact was displayed through my artwork: For my identity project, I drew myself as a skeleton, as if to say: ‘See! I’m just as human as you beneath the skin that you ostracize me for!’”

Mona Shah, Oakland

“When I was a teenager in the late ‘80s, I was attending an Indian Hindu wedding in Artesia, Calif., dressed in traditional clothing (sari) and was crossing the street to the community hall where festivities were taking place, when a couple of people in their cars told me that it was not Halloween and that I should go back to my country.

“It made me feel angry, ashamed and very sad that people would feel that about me and how I looked. I always felt out of place growing up and did not consider myself American because I was constantly asked where I was from as if I did not belong here, although I was born in the U.S.”

Alicia San Miguel, San Antonio

“I was 15 years old in pre-AP world history in Amarillo, Texas. The boy behind me … said, ‘Why don’t you go back to Mexico, you dirty Mexican?’ I remember being so frustrated because: My race or ethnicity had nothing to do with the discussion; I’m a U.S. citizen, no different than that boy (my family is of Mexican descent, but I’m a third-generation American); and I was one of a handful of minority students at this campus. His words weren’t an accident.... It was an early reminder that people will use your appearance against you, your race, your ‘otherness’ in their eyes, to punish you for having a voice, for daring to be an equal.”

Christine Lee, Monterey Park

“Over 30 years ago, I attended a mostly white private Christian school in Orange County. I was 5 years old when a classmate told me to ‘go back to where [I] came from’.... She made fun of my “chinky eyes” ... and called me Chinese. As a Korean American, I was a handful of nonwhite kids at that school. She did this for days on end and no teachers, administrators or other students intervened or even noticed what was going on. Never mind that I was born here and the U.S. was the only home I’d ever known.

“It didn’t stop until my dad figured out why I was coming home with lacerations and dirt on my face and tears in my eyes …. [She] was my first bully and not the last time I would hear someone say that racist phrase to me. Never in my lifetime did I imagine that someone in the office of the president of the United States would say those same words.”

M.H., Los Angeles

“I’m African American, and to this day people still ask me, ‘Where are you really from?’ and suggest that I’m probably a new transplant. My family has been here for centuries and generations. We hail from Cherokee and Iroquois nations, the slave trade and immigrants from Barbados.

“When I was younger, ‘Go back to Africa’ was meant as a taunt. And my aunt taught me to respond with, ‘All humankind is from Africa, so you can always go home too.’ But as a young person, that never took the sting out of it.

“As a 49-year-old woman, these phrases say much more about them than it does about me. But their words are clear. I don’t belong here.”

Mary Bernard and Javier Panzar contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.