It took 13 years, two trials and an army of accusers to convict Bill Cosby of one sexual assault

- Share via

It was 2005 when Andrea Constand reported that a year earlier, when she was manager of the women’s basketball team at Temple University, she had been drugged and sexually assaulted by her mentor at the school — Bill Cosby.

Prosecutors declined to file criminal charges against the comedian and television icon, citing insufficient evidence.

It would take 13 years, two trials and an army of other accusers coming forward for Constand to be vindicated.

On Tuesday, Cosby, 81, was sentenced to three to 10 years in prison by a Montgomery County, Pa., judge and led away in handcuffs, having been convicted of three counts of aggravated indecent assault for drugging and molesting Constand.

He is the first major celebrity imprisoned in the #MeToo era, in which sexual assault and harassment victims have been emboldened to come forward to hold powerful perpetrators to account.

Such claims, when published in the media, have forced powerful politicians and businessmen to resign their posts and raised the expectations for schools and workplaces around the nation to prevent abuse.

But proving those allegations in criminal court is another story, and Cosby’s conviction shows how difficult that remains.

The case isn’t the only sexual assault story dominating the headlines this week. The #MeToo movement is navigating its most unusual and partisan arena yet, as the U.S. Senate weighs how to evaluate allegations of sexual misconduct by Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh when he was a student in the 1980s.

Senators and media figures have argued over the appropriate standards to use in evaluating the truthfulness of one woman accusing Kavanaugh of attempting to rape her in high school and another accusing him of taking out his penis and putting it close to her face in college.

Kavanaugh has strongly denied both allegations, and some of his Republican supporters have suggested the allegations have been concocted by Democrats for political reasons. Democrats, in turn, have accused Republicans of downplaying the allegations for political reasons.

Kavanaugh critics who argue that the allegations should disqualify him from the Supreme Court have cited the #MeToo movement’s imperative to presume accusers are telling the truth, while Kavanaugh defenders have cited the criminal justice system’s presumption of innocence unless found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

The distinction between the two standards matters a great deal, and Constand’s long journey to secure a conviction against Cosby illustrates why.

The criminal justice system declined to prosecute her allegations against Cosby for more than a decade, until a wave of media reports revealed that at least 60 women had accused Cosby of sexual misconduct.

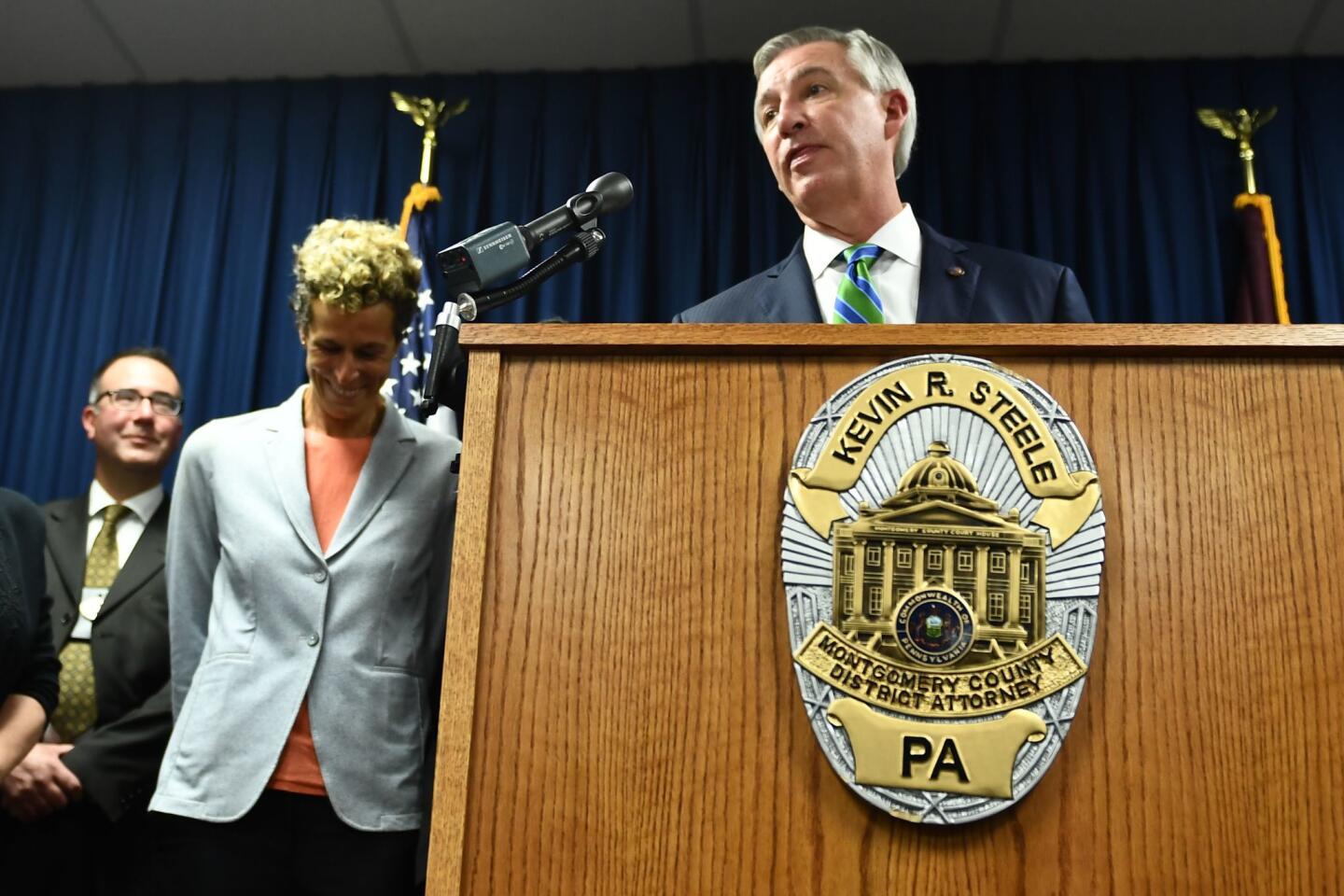

The 2015 election of a new Montgomery County prosecutor, Kevin Steele, brought renewed interest in pursuing charges against Cosby, along with the revelation that Cosby had admitted in a deposition in a civil lawsuit that he had drugged women with quaaludes to have sex with them. Cosby was arrested and charged later that year, shortly before the expiration of the statute of limitations.

A trial in 2017 ended with a hung jury, but in a second trial this year, multiple women were allowed to testify, making allegations that were similar to those by Constand.

Cosby maintains his innocence, and his lawyers plan to appeal his conviction.

The criminal justice system’s standards are often hard to meet for sexual assault victims. Fewer than a third of sexual assault victims report it to the police, and fewer than 4% of victims see their perpetrators convicted and imprisoned, according to statistics from the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, an advocacy group known by the acronym RAINN.

Which would make Cosby’s sentence an extreme exception regardless of how long it took to achieve justice.

“We are grateful that the court understood the seriousness of Cosby’s crime and sentenced him to prison,” RAINN said in a statement. “Let’s hope that the legacy of this case is that victims feel empowered to come forward, knowing that it can truly make a difference in bringing perpetrators to justice.”

In a lengthy statement Tuesday telling her story, Constand described the 2004 drugging and assault and how all the strength and agility she possessed as a 30-year-old former professional basketball player melted away.

“Instead of being able to run, jump and pretty much do anything I wanted physically, during the assault I was paralyzed and completely helpless,” she said. “I could not move my arms or legs. I couldn’t speak or remain conscious. I was completely vulnerable, and powerless to protect myself.”

Timeline: Bill Cosby: A 50-year chronicle of accusations and accomplishments »

She withdrew from her family and friends, stopped eating and was kept awake by nightmares.

Today she is “a middle-aged woman who’s been stuck in a holding pattern for most of her adult life” because of her long-protracted pursuit of justice for what Cosby did to her, she said.

Constand also described the heavy burden of needing to be believed.

“The pressure was enormous,” she said. “I knew that how my testimony was perceived — that how I was perceived — would have an impact on every member of the jury and on the future mental and emotional well-being of every sexual assault victim who came before me. But I had to testify. It was the right thing to do, and I wanted to do the right thing, even if it was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.”

Matt Pearce is a national reporter for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @mattdpearce.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.