Sinaloa cartel thrived, whether boss was in prison or on the lam

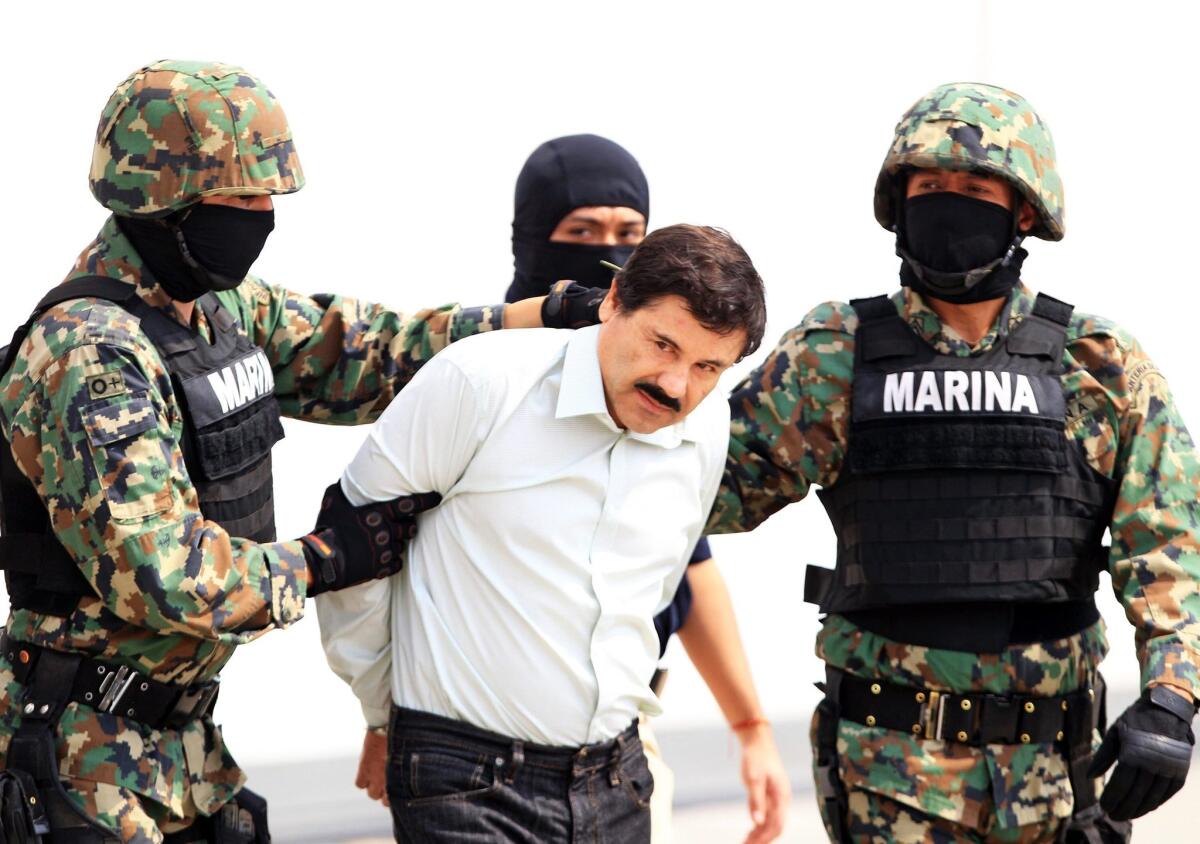

Mexican drug lord Joaquin Guzman after he was taken into custody in 2014.

- Share via

Even as authorities fanned out across Mexico on Monday in search of Joaquin Guzman, the drug kingpin known as “El Chapo” whose weekend escape was straight out of a Hollywood script, Guzman’s cousin was miles away in New Hampshire, facing sentencing in an international cocaine distribution case.

The cousin, Jesus Manuel Gutierrez Guzman, allegedly plotted with the notorious leader of the Sinaloa drug cartel to establish a beachhead in New England, setting up a plan to distribute 1,000 kilograms of cocaine and other drugs to the northeastern U.S.

The fact that “El Chapo” was on the lam after an earlier escape in 2001 seems not to have hampered the plot, which was tripped up by federal informants and finally ended when the Guzman cousins and several associates were indicted by a federal grand jury in New Hampshire.

Nor did the years “El Chapo” spent behind bars, until his second escape on Sunday, appear to have diminished the reach of the Sinaloa organization. Investigators say Mexico’s largest and most lucrative drug cartel has remained active around the world, from Australia to Italy, even after Guzman’s latest capture in 2014.

Whether on the lam or in jail, Guzman continued to run his powerful cartel through a network of business tentacles that stretched to some of the most unlikely places -- including the easternmost town in New Hampshire.

Like many an organized crime figure before him, El Chapo kept a tight rein on the cartel through a bureaucracy of trusted aides and relatives including his cousin, who pleaded guilty in the New Hampshire case and faces up to 33 years in prison.

The New Hampshire plan was hatched, according to Gutierrez Guzman’s plea agreement, to help carry out the Sinaloa leader’s wish to expand the cartel’s trafficking operations into Europe and in the U.S. north of Boston.

Prosecutors say El Chapo personally met with associates to work out details, even though he was in hiding after his first escape from a Mexican prison.

“The deal was consummated by a face-to-face meeting with Chapo and several telephone calls in which he himself discussed details of the intended shipments,” prosecutors said of talks in 2009 on opening the new distribution network.

Gutierrez Guzman had been scheduled to be sentenced on Monday, but the proceeding was delayed in Concord to allow probation authorities to respond to defense objections about how federal sentencing guidelines were being applied.

The New Hampshire case was previously described by acting U.S. attorney Donald Feith as the cartel seeking to establish “a toehold” that could be expanded.

“It’s not just a USA thing,” Rusty Payne, a spokesman for the Drug Enforcement Administration in Washington, told the Los Angeles Times on Monday. Sinaloa drug dealers “operate around the world,” he said, with activities traced to Africa, Europe and Australia.

“They are pretty diverse, a global empire,” he said.

The fugitive cartel leader was one of those indicted in the New Hampshire case, as he has been in proceedings in California, Texas, Arizona, Chicago and New York City.

The most recent charges, unveiled in Brooklyn in October, accuse the drug leader and associates of hundreds of cases involving murder, assault, kidnapping and torture. Guzman also faces a potential death penalty case in Texas.

By that standard, the New Hampshire case is relatively small, carrying a sentence of at least 10 years to a maximum of life in prison. But the case does provide what prosecutors say is a blueprint into how the cartel operates.

The case began in July 2009, when authorities said they discovered “a link” in Massachusetts to the cartel. An unidentified source working for the FBI met Gutierrez Guzman and another person, Samuel Zazueta Valenzuela, in Mexico, according to court documents.

The pair and two others were seeking new cocaine distribution routes from South America to Europe, Canada and the United States, prosecutors allege.

Months after the initial contacts, Gutierrez Guzman and others flew to a mountainous region near Culiacan, Mexico, where they met with El Chapo, according to a plea agreement signed by the cousin.

In early 2010 through about August 2012, undercover FBI agents posed as members of a European organized crime syndicate and met with representatives of the group, including the cousin. Many of the meetings were recorded by audio and video, and portions have been played in open court, according to prosecutors.

The recordings depict meetings in Miami, Boston and in Madrid. Meetings were also held in New Hampshire in Portsmouth and New Castle, a town with about 1,000 people, located entirely on islands in the far eastern part of the state.

At the meetings, the group members said they could bring “thousands of kilograms” of cocaine from countries including Bolivia, Panama, Belize and Colombia to various ports on the northeastern seaboard of the United States, prosecutors said.

On July 27, 2012, the group allegedly delivered a test shipment for the new network: 346 kilograms of cocaine, worth millions of dollars, to a port in Algeciras, Spain. The drugs were in a cargo container in boxes that purportedly held glassware, according to prosecutors.

The FBI seized the cocaine and four were arrested in August 2012. In addition to Gutierrez Guzman, three others -- Zazueta Valenzuela, Rafael Humberto Celaya-Valenzuela and Jesus Palazuelos-Soto -- were taken into custody.

All four were extradited to New Hampshire. They and others, including Joaquin Guzman, were named in a superseding indictment that accused them of conspiring to distribute more than 1,000 kilograms of cocaine and other drugs.

Celaya-Valenzuela was convicted after an October 2014 trial of conspiracy to distribute controlled substances, including cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine. He is awaiting sentencing.

The others, including El Chapo’s cousin, all pleaded guilty before trial. Soto was sentenced to 108 months; Zazueta Valenzuela was sentenced to 120 months.

Follow @latimesmuskal for national news.

Hoy: Léa esta historia en español

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.