Despite California’s budget surplus, unions eye tax hikes

A group of unions in California are pushing a ballot measure to continue Gov. Jerry Brown’s so-called temporary tax hike 12 years beyond its scheduled Dec. 31, 2018, cutoff.

- Share via

in SACRAMENTO — Here is one thing for California to be thankful for: The state treasury is overflowing with tax money.

Long gone are the dark years of multibillion-dollar deficits — $42 billion in 2008 — and sharp cuts in state services, especially healthcare for the poor and education.

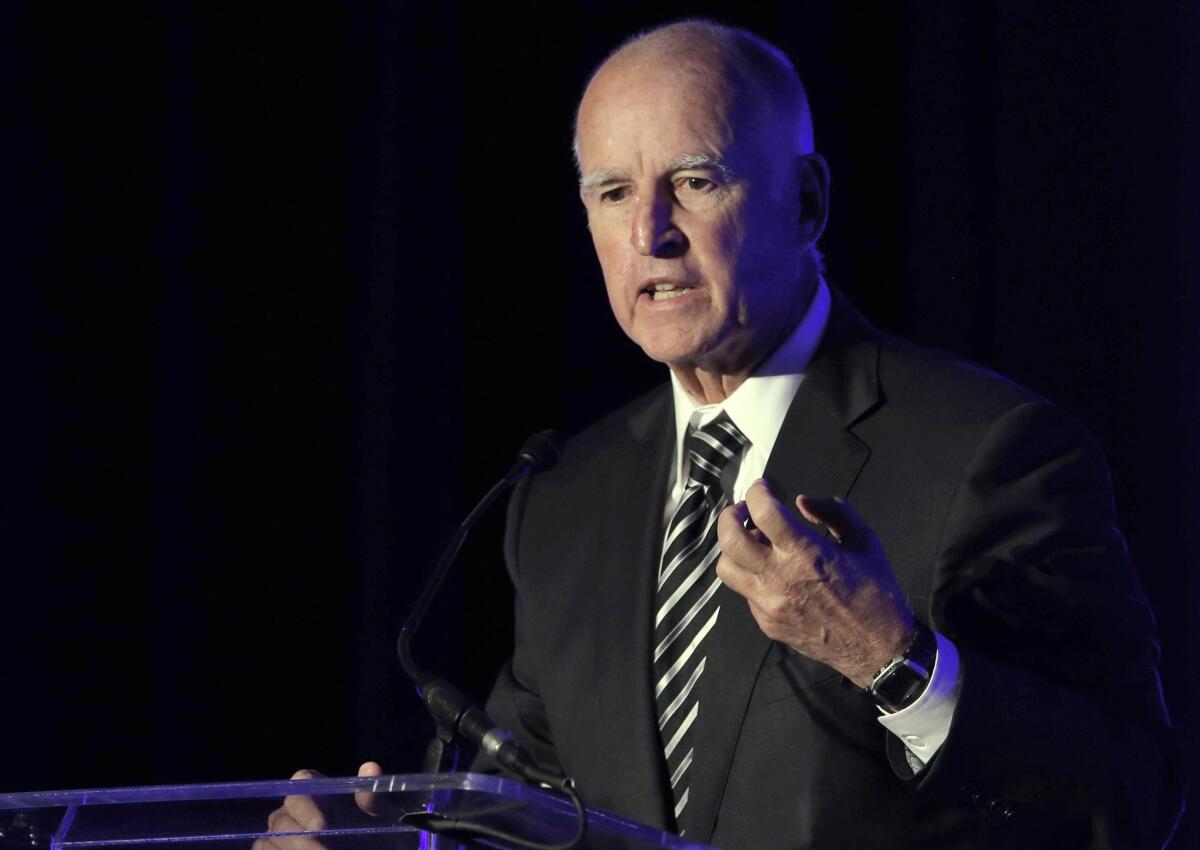

Credit the recovering national economy. Gov. Jerry Brown also gets a high-five for holding big spenders in check. But the governor’s 2012 voter-approved, soak-the-rich tax hike was a crucial budget healer.

The nonpartisan legislative analyst’s office reported last week that the state’s tax take for the current fiscal year is expected to exceed earlier estimates by $3.6 billion. And by the end of the next fiscal year, the state is on track to have $11.5 billion in reserve.

“The state budget is better prepared for an economic downturn than it has been at any point in decades,” analyst Mac Taylor announced.

Great. But what happened the next day is the sort of thing that makes so many voters cynical and motivates some Californians to still list themselves as Republicans.

A proposed ballot measure to continue the so-called temporary tax hike 12 years beyond its scheduled Dec. 31, 2018, cutoff was cleared by the secretary of state for signature collection. The initiative’s sponsors are the California Teachers Assn. and the state Services Employees International Union.

That’s right: The treasury is spilling over, but some unions want to keep collecting income taxes at the highest rate in state history.

Gale Kaufman, political strategist for the teachers union, asks, “Why take a chance on who’s right and who’s wrong” about whether the economic recovery will continue?

Brown’s tax hike, Proposition 30, “brought in necessary revenue at a time when we’d seen devastating cuts and teacher layoffs,” she says. “Why would we want to turn back to any of that?

“No one can argue that schools are back to where they were.”

The teachers union contends that $50 billion in education cuts will never be made up, that inflation-adjusted funding still is $1 billion under the 2007 level and that K-12 spending, when factoring in California’s high cost of living, ranks 42nd in the nation.

But it could be a tough sell.

Before the recession hit, K-12 schools and community colleges in 2007 were receiving nearly $57 billion under Prop. 98 guarantees — $42 billion from the state and about $15 billion from local property taxes. That fell to a total of $49 billion the next year. But this fiscal year, the schools are expected to rake in more than $68 billion — more than $49 billion from the state and $19 billion from property taxes.

To put that $49 billion of the state’s money in perspective, the current general fund budget is $115 billion.

Moreover, there’s bound to be yelping from critics who complain that the state and unions are dragging their feet on education reform.

“If you don’t want to do something, like pay more taxes, you can always come up with a reason,” Kaufman says.

Prop. 30 raised the top income tax rate for the wealthiest Californians from 10.3% to 13.3%. It also imposed a token quarter-cent sales tax hike. The initiative would allow the sales tax bump to expire at the end of next year.

This fiscal year, the Prop. 30 take is estimated at $8.3 billion — roughly $6.7 billion from income and $1.6 billion from sales. Under the initiative, revenue from the additional income tax would be split between K-12 schools, getting 89%, and community colleges, 11%.

But stay tuned. There’s a rival Prop. 30 extension being proposed by the California Hospital Assn., the California Medical Assn. and one chapter of the service employees union. It would extend the higher income tax rates permanently, making no pretense of “temporary.”

Under this measure, 40% of the revenue would go to K-12 schools, 5% to community colleges, 5% to universities, 40% to healthcare and 10% to child care and development.

It could be a political disaster to have two competing tax hikes on the ballot. So the two sides are negotiating in an effort to create one compromise proposal.

“There are a lot of moving parts,” says Dan Newman, spokesman for the second measure.

But why is a tax increase justified at all when the state is wallowing in money?

“Pretty simple,” Newman says. “It’s a fundamental moral choice. It’s true that many wealthy Californians are doing great. But millions of other California families will have better lives with more resources for their schools and healthcare.”

Brown probably will be neutral on the measure, having billed his tax increase as temporary.

Actually, given the era, this tax hike may not be such a hard sell after all.

There’s a lot of resentment about the widening wage gap, with the rich getting richer and the declining middle class losing earning power with stagnate pay.

There may not be a lot of money thrown into the opposition campaign. The measure wouldn’t tax the usual big-business donors, only individuals.

There’ll be a relatively large turnout of Democrats in next November’s election to vote for president, and they’ll probably enjoy taxing the rich. Moreover, women — who usually care more than men about education — will probably be turning out in big numbers to vote for potentially the first female president.

So another thing to be thankful for is all the rich people to soak — and especially thankful because they’re not fleeing the state.

Twitter: @LATimesSkelton

ALSO

Perspective: Being black is exhausting, and here’s why

L.A.’s ‘soft targets’ draw more scrutiny in the wake of Paris attacks

While other areas are bone dry, San Diego has too much water

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.