Even in a booming economy, L.A. City Hall faces daunting budget challenges

- Share via

Standing outside City Hall, Mayor

Garcetti described the city’s emergence from a recession that, in his words, sapped the public’s morale and “gutted” basic services. “We … got back to work one street tree, one sidewalk, one pothole at a time,” he told the audience last month.

Los Angeles is indeed spending more on its streets, sidewalks and other infrastructure. Yet even in a booming economy, Garcetti faces a daunting set of budget challenges — including a projected gap of more than $200 million in two years, budget estimates show.

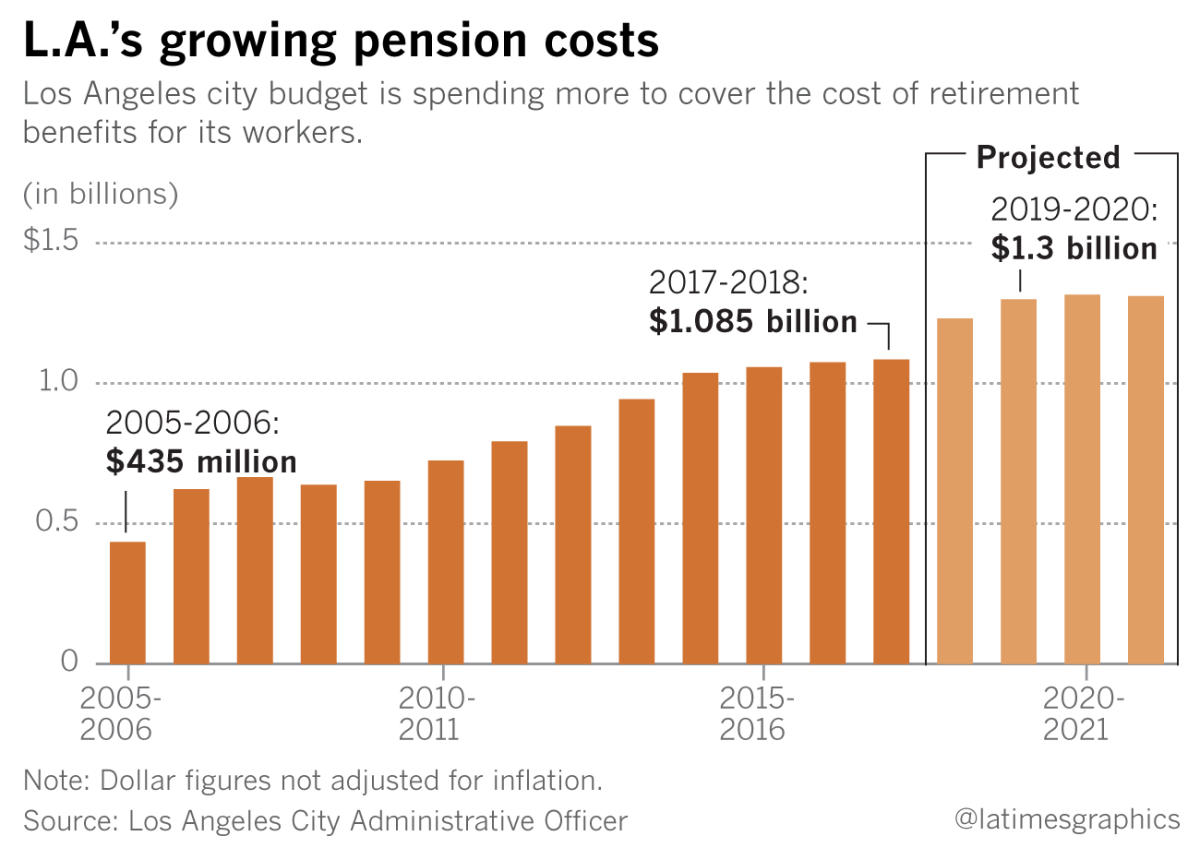

The city continues to face a “structural deficit,” with projections showing expenses exceeding the money that comes in. Retirement costs are poised to jump significantly, consuming funds that would otherwise pay for public services. And if another downturn hits, Garcetti will have less room to maneuver than in the last recession — thanks to decisions he and the City Council have made.

In recent years, the mayor and city lawmakers have signed off on legal settlements that dictate how much the city must spend on sidewalk repairs and on affordable housing for disabled renters.

Garcetti and the council also endorsed a legal agreement that, if approved by a judge, would limit the amount of money sent to the city budget by the Department of Water and Power. And they have reduced business taxes in a way that would be difficult to reverse during a crisis.

Those budget constraints represent more than $100 million per year in lost revenue and additional financial commitments, a Times analysis found. And they will tie the hands of city leaders for years to come, said City Controller Ron Galperin.

“In the next downturn, that means there is going to be very, very little wiggle room” to balance the budget, he said.

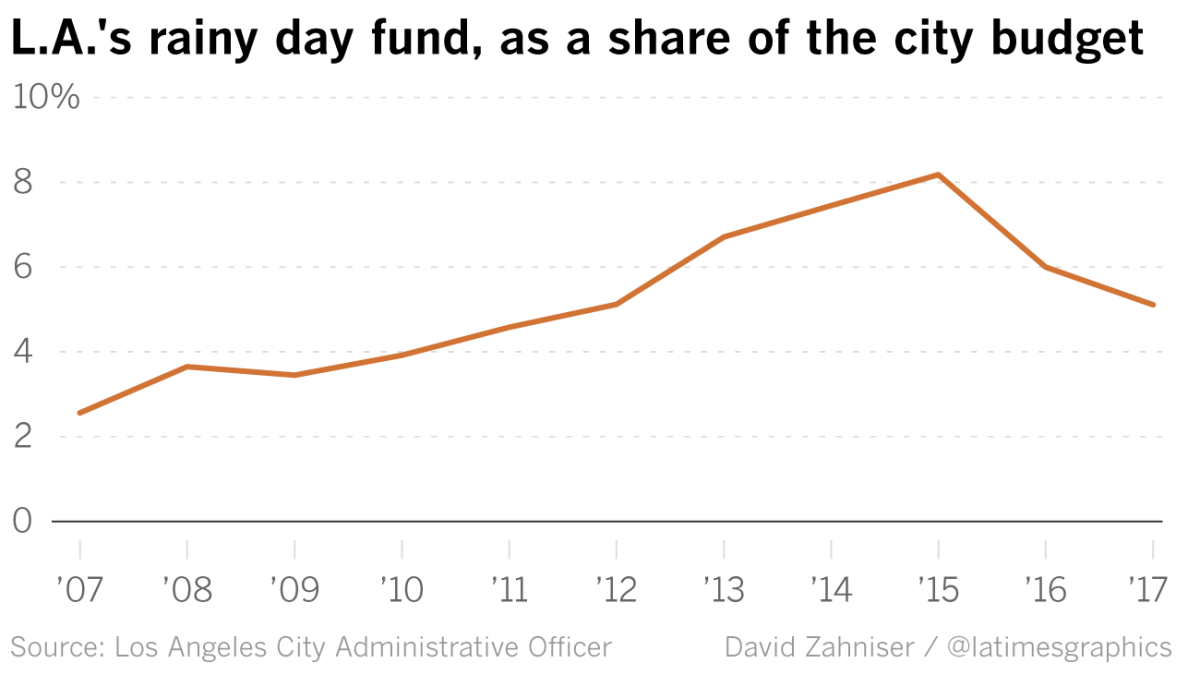

Garcetti, in an interview, argued that the city’s finances are “quite strong.” Since the recession, he said, city leaders have built up more than $400 million in reserves, double the amount available a decade ago.

“There’s no question we’re in a better position than we were in 2008,” he said. “We’re more efficient. We have more in reserves. We’ve been much better at increasing the staff in a prudent way.”

Garcetti defended the sidewalk spending agreement, saying he would have pushed for the repairs anyway, and described the DWP settlement as “one we can live with.” But he also argued that city leaders are working to bring in new sources of funding, including taxes on

“There are revenues that make this not a one-sided story,” he added.

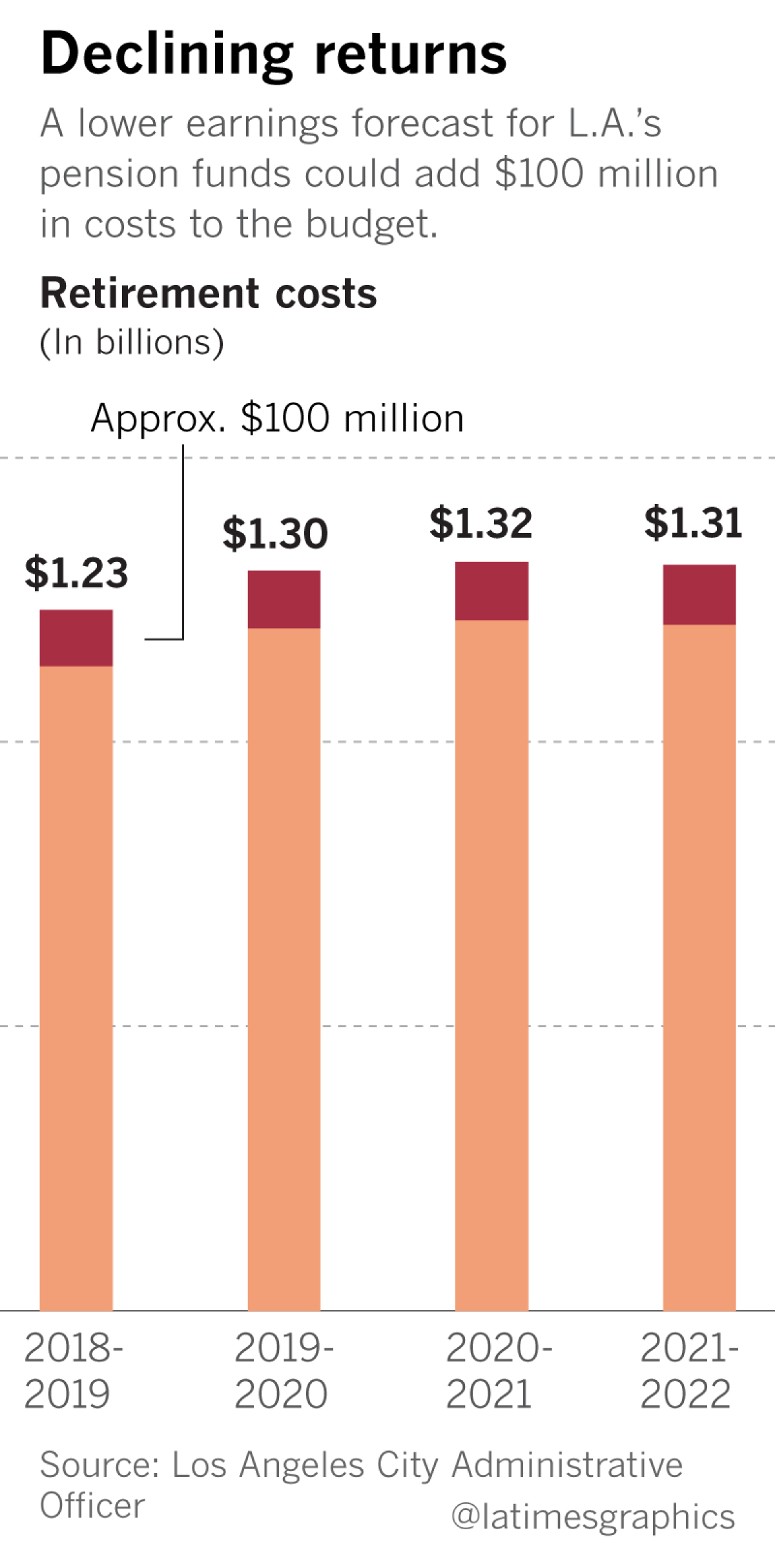

Still, that money might not be enough. An analysis released by the city in April indicated that the general fund budget, which pays for police patrols, firefighter response and other basic services, could see a nearly 20% jump in pension and retiree healthcare costs by 2019.

That would push the city’s retirement costs up to $1.3 billion. Councilman Paul Koretz, who heads a committee on personnel issues, voiced fears about the city’s ability to absorb such an increase in hard times.

“If we had a big economic downturn,” he said, “we’d have to fill [the gap] by reducing services and probably laying people off.”

The last time Los Angeles faced a recession, the city’s elected officials were caught off guard.

When the downturn hit in 2008, they had just approved five years of employee raises totaling nearly 25% for most civilian city workers. They also had hired hundreds of new police officers.

What followed were service rollbacks in libraries, parks, the Fire Department and other agencies — and the departure of thousands of city employees. The crisis was exacerbated by major investment losses for the city’s pension funds, which made the budget picture worse.

The city’s pension agencies have seen stronger returns since the recession. But elected officials are about to confront a new round of challenges.

The looming pension threat

In June, the agency that oversees pensions for retired police officers and firefighters cut its “assumed rate of return” — its yearly earnings projection — from 7.5% to 7.25%. The Fire and Police Pensions board concluded that their investments would not produce returns as strong as previously forecast.

When the pension board reduces its investment projections, taxpayers — and the city budget — frequently make up the difference. But the board also updated its long-range forecast to reflect the reality that its retirees are living longer and will need pensions for a greater number of years.

Those actions are expected to increase the city’s employee retirement costs by $84 million next year, according to recent estimates.

A second pension board, which serves civilian city workers, is set to consider a similar set of costly changes. If it follows the lead of Fire and Police Pensions, the city could see at least $38 million in added costs, officials say.

The increased retirement costs are set to hit the city budget next year, when Garcetti and the council are slated to finalize new contracts with two big employee groups: the Police Protective League, which represents rank-and-file police officers, and the Coalition of L.A. City Unions, which represents civilian workers.

Art Sweatman, a tree surgeon supervisor with the Bureau of Street Services, said many city workers are struggling to keep up with rising rents and home prices.

“We need to keep up with the cost of living,” he added.

For every 1% pay increase given to police officers and coalition workers, the city will need to spend an additional $22 million, according to city estimates. And because pension benefits are based on salaries, those raises will ultimately add to the overall retirement burden.

City budget analysts say their pension cost projections could change significantly depending on hiring decisions, the size of raises and the economic performance of the two funds. But if their figures prove to be accurate and retirement costs grow by nearly 20%, the city would have to cut spending, bring in more money or tap reserve funds.

Scarred by the experiences of the last recession, city leaders steadily built up the reserve over the past decade. But they have also chipped away at it in recent years, using it to balance the budget and pay for programs to address homelessness.

Cutting costs in the next recession

Faced with a crisis, city leaders could do what they did last time — scale back public services. But some of those reductions won’t be as easy next time.

Take sidewalks. When the global recession hit in 2008, city leaders halted funding for repairs, adding to an already sizable backlog of buckled pavement.

Soon after that decision, advocates for the disabled filed a lawsuit arguing that L.A.’s network of broken sidewalks violated the civil rights of wheelchair users. They demanded a citywide commitment to repairs.

Garcetti and the council settled the case once the economy recovered, promising to spend at least $31 million a year on repairs. That obligation jumps to nearly $36 million after five years and to $41 million after a decade.

Even if a downturn hits, the city must spend no less than $25 million per year to remain in compliance with the settlement agreement, according to Garcetti aides. That means they likely would have to look elsewhere for cuts.

They won’t have much success reducing library hours, another area hit during the last recession. That’s because voters passed a 2011 ballot measure increasing the minimum funding for libraries — an initiative placed on the ballot by Garcetti and other city elected officials.

Cuts at the Recreation and Parks Department also wouldn’t make much of a dent, since that agency is also guaranteed a specific share of funding.

The city also has new spending obligations on housing.

Last summer, Garcetti and the council signed off on a legal settlement that requires city officials to spend at least $200 million on housing for disabled renters over the next 10 years. This year, in the first year of that agreement, $11 million is coming from the budget for basic services.

City funds could soon be limited in other ways, thanks to yet another legal fight.

Forfeiting revenue

Like many mayors before him, Garcetti has relied on the DWP to send the city budget what is billed as a yearly “surplus.” But that practice has become the target of legal challenges, with ratepayer activists calling the money an illegal tax.

In an effort to settle those cases, Garcetti and the council cut the size of the payment to $242 million, down roughly $25 million from the previous year.

As part of the proposed settlement, city leaders agreed to limit the amount the DWP can transfer in future years. That would impede the city’s ability to increase the funds taken from the DWP during a crisis, something previous mayors have done.

L.A.’s budget faces new constraints — financial commitments and forfeited revenue

- Sidewalks: $31 million in yearly repairs

- Business tax cut: $45 million per year in lost revenue

- Disabled housing: $20 million in yearly expenses

- DWP settlement (proposed): $25 million in reduced revenue

The city is also scaling back the business taxes it collects from key companies — lawyers, financial planners and other professional service firms. Garcetti secured passage of the reduction, which is being phased in over three years and is expected to remove $45 million annually from the budget.

Garcetti contends that business tax cuts, pursued strategically, stimulate the economy and ultimately produce more money for the budget. Still, if he changes his mind, he and the council would have a difficult time undoing their decision.

Under state law, any increase in the business tax would require a ballot measure and a citywide election, according to policy analysts.

The search for more money

Despite the looming budget pressures, Garcetti and the council managed to boost spending in two major areas this year: transportation and programs to address homelessness. Both were possible because voters agreed to tax themselves in the November election.

Garcetti and city lawmakers have been eyeing other sources of additional money.

In the mayor’s latest budget, the city is expecting a $36-million increase in lodging taxes, almost all of it from Airbnb and other short-term rental services. That assumption has infuriated some housing advocates, who contend that Airbnb disrupts neighborhoods and drives up rents.

The mayor is also looking to generate $12 million this year from placing digital billboards on city property. But that strategy has not yet been approved by the council — and could face opposition from neighborhood groups.

Then there is the biggest windfall of all: an estimated $50 million per year from marijuana retailers, who are looking to operate legally in the wake of recent ballot measures on pot sales.

The city’s strategy drew criticism from Laura Lake, a Westwood resident who fought one of the city’s last big money-making strategies — 50-year leases of municipal parking garages. The city is “desperate” for funds, she said, and is turning to solutions that will seriously affect neighborhoods.

Lake described digital billboards as a form of blight and argued that Airbnb is depriving Angelenos of rent-controlled housing. Marijuana retailers, because they deal in cash, may place an additional burden on police, she argued.

“I’m surprised the City Council isn’t licensing brothels and casinos,” Lake added. “I mean, why not?”

Garcetti contends the city’s work on marijuana, billboard and home-sharing regulations is based on good policy, not a hunt for revenue. At the same time, he made clear he wants those funds to flow into the city budget.

“The voters passed marijuana [sales] and I’ll be damned if the city isn’t going to get some money from those increased sales, period,” he said.

ALSO

A 5% rent increase would push 2,000 Angelenos into homelessness, study warns

Congress takes aim at the Clean Air Act, putting California's limits of power to the test

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.