Sy Berger dies at 91; father of the modern-day baseball card

- Share via

On a garbage scow off New Jersey, an executive for a powerful organization was getting rid of a costly problem. He watched in silence as a lever was pulled and box after box plunged into the dark waters: Goodbye, Mickey Mantle. Goodbye, Jackie Robinson. Goodbye, Eddie Mathews. Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye.

On a nod from Sy Berger, a vice president of the Topps chewing gum company, the crew jettisoned some 2 million 1952 baseball cards that had been clogging up the company’s Brooklyn warehouse for about eight years. Down went cards that had been released too late in the season to generate interest with the boys who were the company’s lifeblood; down went cards that in later years would have bought collectors the garbage scow, the tugboat that hauled it and a passing yacht or two.

But who knew?

“I’m a gatherer, not a collector,” Berger said more than once.

Berger, who is widely viewed as the father of the modern baseball card and who loved to tell the story of his maritime escapade, died in his sleep Sunday at his home in Rockville Centre, N.Y., said his daughter, Maxine Berger-Bienstock. He was 91.

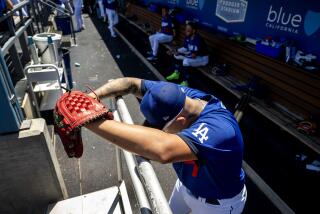

In baseball circles, Berger was as familiar as the seventh-inning stretch. He was a fixture at spring training, the World Series, and workaday games in between. For decades, he waltzed into clubhouses and locker rooms, signing players to contracts for Topps cards and schmoozing with managers, coaches and trainers.

“He was a very savvy businessman but also incredibly loyal and giving,” his daughter said. “He became a confidant for players. If they needed help, he was there for them.”

In a statement, baseball great Willie Mays said Berger “helped me from my first days in the majors.”

“I never could have made it without him,” said Mays, who in later years would accompany Berger to annual Baseball Hall of Fame inductions in Cooperstown, N.Y. “We worked together. We laughed together. We grew up together.”

Berger’s inside-baseball connections were “the stuff of legend,” wrote Dave Jamieson in his 2010 book, “Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Have Become an American Obsession.”

Berger visited minor league parks to sign players at $5 apiece in advance of their hitting it big. When they did, the booty was bigger: $125 a year, sometimes redeemable in home appliances, couches or other goods from the Topps catalog.

Not every player signed on, but most did.

“By 1960, Berger’s relentless networking had helped Topps secure contracts from an astonishing 414 of the major league’s 421 players,” Jamieson wrote. “For a growing number of American boys, the pastime of baseball and the pastime of baseball cards had become one and the same, each hobby fostering the other, as it would for at least another generation.”

Berger also lined up players for trading cards in football, hockey and other sports, as well as negotiating to produce Beatles cards, Michael Jackson cards and a variety of other Topps collectibles.

But he is best known for the cards that Americans — mostly boys — traded, flipped and stuck into their bicycle spokes, sometimes with clothespins, to emulate engine clatter. For years, shoe boxes crammed with cards sat under beds and on closet shelves, almost always meeting the same end: “There isn’t an American boy,” Berger once observed, “whose mother hasn’t thrown his baseball cards away.”

Born in New York City on July 12, 1923, Seymour Perry Berger grew up a baseball-loving boy a few blocks from Yankee Stadium in the Bronx. He studied accounting at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa., where one of his fraternity brothers was Joel Shorin, the son of a Topps co-founder and a future president of the company.

After serving in the Army Air Forces and graduating from college in 1946, Berger returned to New York and sold linens in a department store. In 1947, he took what was supposed to be a temporary job at Topps’ Brooklyn headquarters: helping with sales of Change-ables, one-cent pieces of gum that customers could get at cash registers instead of pennies in their change.

Berger came into his own in the early 1950s, when Topps went after the baseball card market dominated by one of its chief competitors, the Philadelphia-based Bowman Gum Co.

In 1952, Berger and Topps creative director Woody Gelman designed a larger, more colorful card to rival Bowman’s, with player autographs and team logos. At his kitchen table, Berger calculated lifetime and past-season statistics for each player, adding them and brief player biographies to the flip sides.

In 1953, the company produced cards based on oil paintings of each player done by “a little, off-the-wall guy named Moishe,” Berger said. Color photos, often taken at spring practice, soon became the norm.

In 1956, Topps bought out Bowman and, despite legal challenges, was at the peak of the trade for decades.

Berger retired in 1997 but consulted for years afterward.

In addition to his daughter Maxine, his survivors include Gloria, his wife of 68 years; his sons Glenn and Gary; five grandchildren; and two great grandchildren.

“Sy was the face of Topps, so much so that many people out there thought he owned the company,” said Ira Friedman, Topps’ vice president for global licensing.

Topps was purchased in 2007 by Michael Eisner, the former chief executive of the Walt Disney Co., and a private investment group.

“It conjures up an emotional response that has a feel-good, Proustian kind of uplift,” Eisner told the New York Times.

In a 2002 interview with the Associated Press, Berger framed the uplift differently.

“We wanted to make something attractive that would catch the eye,” he said. “And we gave you six cards and a slice of gum for a nickel.”

Twitter: @schawkins

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.