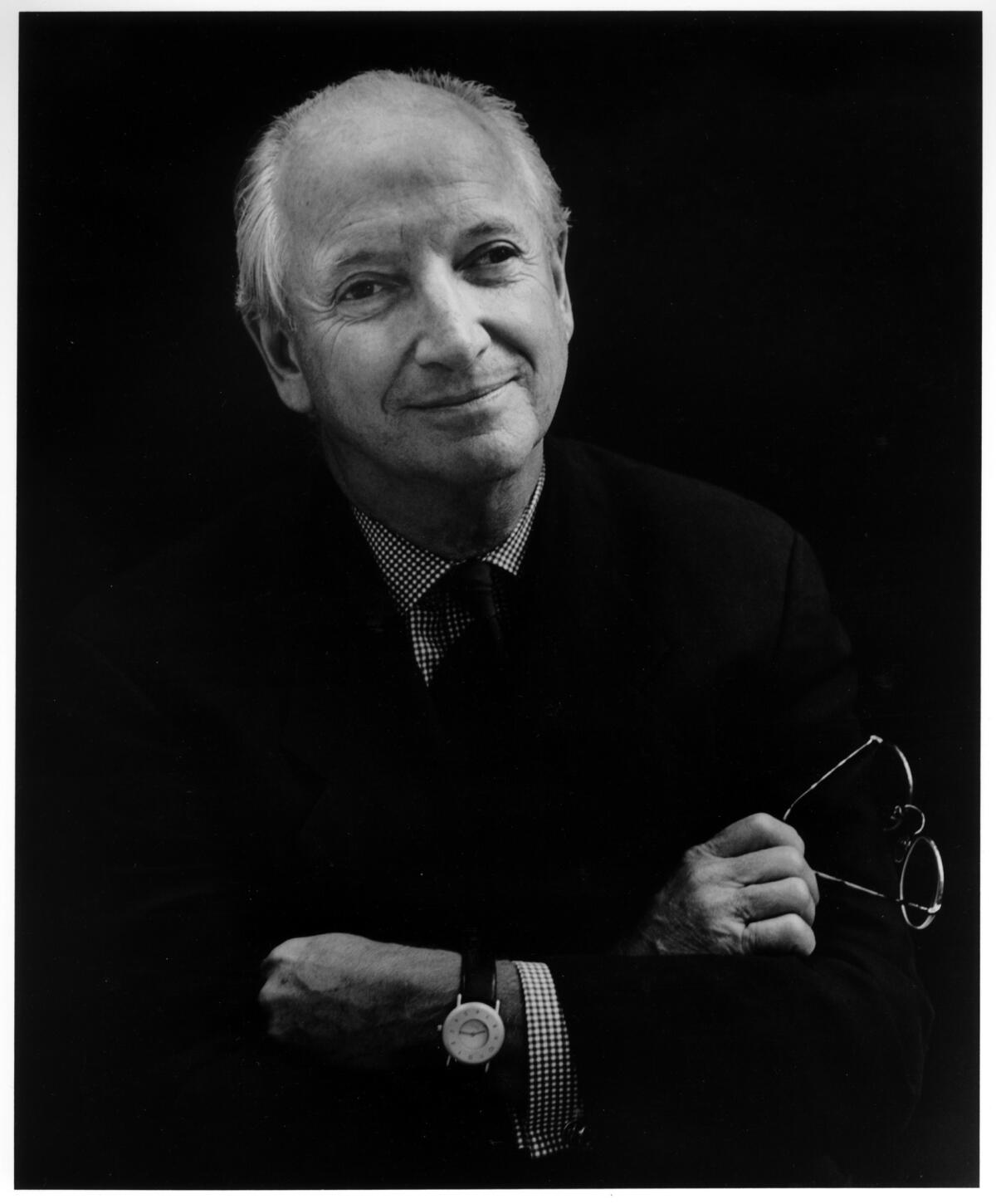

Michael Graves dies at 80; pioneering figure in postmodern architecture

- Share via

Not many architects can claim to have spearheaded a major design movement. Michael Graves played a prominent role in three.

Graves, who died Thursday at 80 of natural causes at his home in Princeton, N.J., was a pioneering figure in postmodernism in the 1980s and ‘90s. He added historical ornament and bright color to prominent and often controversial buildings like the Portland municipal building in Oregon, the Denver Central Library, the 26-story Humana tower in Louisville, Ky., and the Disney Studios in Burbank.

As a product designer, creating chess sets, stainless-steel colanders and dustpans for Target and tea kettles for Alessi, Graves brought high-design housewares to a broad public, paving the way for the later success of Design Within Reach and Ikea and arguably setting the stage for the ascendance of new stars like Apple’s in-house design guru Jonathan Ive.

Late in life, after complications from a sinus infection left him in a wheelchair, Graves became a leading voice calling for reform in healthcare design, arguing that hospitals and medical products were not just thoughtlessly made but often soul-sapping for patients.

If there was a thread connecting that disparate work, it was a deeply felt populism, a philosophy embodied in the slogan Target attached to his products: “Good design should be affordable to all.”

His architecture, similarly, represented an effort to bring back all the crowd-pleasing details — columns, gables, gargoyles — that dour modernist architects, with their emphasis on flat roofs and functionalist dogma, had banished. Though many of his buildings had a limited, scenographic quality — more effective as eye-catching billboards for innovative design ideas than as built space — and haven’t aged well, they were always full of vitality and humor.

Graves was born in Indianapolis on July 9, 1934. After earning a degree in architecture from the University of Cincinnati in 1958, he enrolled at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, a place very much still in thrall to the ideals of strict modernism. After finishing at Harvard and spending two years at the American Academy in Rome, Graves settled in New Jersey, joining the Princeton University faculty, where he would spend his entire teaching career, and opening his own practice.

Early on, Graves’ architecture reflected the influence of his time at Harvard. He was a member (with Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey and John Hejduk) of the so-called New York Five, a collection of young architects who produced abstract designs reminiscent of the French modernist Le Corbusier.

But the group was always a loose-knit one philosophically; they first came together almost by chance, having been invited by Museum of Modern Art curator Arthur Drexler to meet in 1969 to discuss their work and contemporary design. The 1972 book “Five Architects” nearly cemented their reputation as a coherent group.

But only nearly. And it was Graves who broke from the pack — and proved how flexible its bonds had always been — by beginning to look to history and ornament as sources of explicit inspiration. In fact an important early project, the 1972 Snyderman House in Fort Wayne, Ind., was completed the same year “Five Architects” was published, while undermining some of its modernist principles.

The house rejected the open plan central to modern residential architecture, separating the interior into traditional rooms. The house burned to the ground in 2002.

In 1979, when he still had a modest national profile, Graves won a competition to design a municipal building in Portland, Ore. Architect Philip Johnson, a Graves admirer and consultant to the competition jury, recommended him strongly enough to persuade the jurors to overlook the young architect’s limited track record.

The building, completed in 1982, is widely considered the first built example of postmodern architecture, with the hints of a new approach visible in Graves’ early houses now used at large and insistent scale. The building is a broad-shouldered office block set atop a two-story base. Pilasters, keystones and other elements of classical architecture are blown up to almost cartoonish size and used to decorate the exterior of the upper floors.

Controversy greeted the design even before construction began. Graves was denied a bid to handle the office interiors, and as a result always claimed was what finally built reflected a compromised version of the original design.

But some people — and some Portlanders — hated most of all the exterior of the building, over which Graves had much fuller control. Modernist architects saw it as a betrayal; classicists found its historicism flimsy.

In recent years the building has been the subject of a fierce preservation debate in Portland. Graves traveled to Portland to defend the building last October in an onstage conversation with architecture critic Randy Gragg.

“I’ve done 350 building designs,” Graves said, “and I don’t have this controversy anywhere else. I don’t know where the hostility comes from.”

He added that the building’s budget of $24 million had left him hamstrung. “The floor-to-ceiling height is low because of the budget, not the architect,” he said.

In December, Graves told a reporter that officials in Portland had assured him the building would be saved, renovated rather than demolished to make way for a new office tower, as had been rumored.

In the early 1980s Graves fell in with a number of designers, brought together by Italy’s Ettore Sottsass, known as the Memphis group. Many aimed to bring postmodernism to product and furniture design.

Graves’ best-known design for the Italian company Alessi, the 9093 kettle, was first produced in 1985. It is made of stainless steel and has a signature red, bird-shaped whistle.

He began working with Target the following decade. The architect designed a special scaffolding to cover the Washington Monument during restoration work that was funded in part by Target. That connection led to a collaboration that helped change the reputation of designer and client alike.

“They asked me to lunch,” he told the New York Times in 2011, “and said, ‘We’ve been knocking you off for 20 years,’ and said, ‘Maybe you’d like to come and try designing for us, if we can keep the price at a Target range.’”

Full-on kitsch appeared in Graves’ architecture by the 1980s. His Disney Studios in Burbank, now the Michael D. Eisner building, uses terra-cotta dwarfs to hold up the classical pediment that crowns the design. Graves later designed resort buildings for Disney in Orlando, Fla., as well as a 1989 hotel for Disneyland Paris.

In 2003 Graves had a painful sinus infection he couldn’t shake. When he began feeling back pain he went to the hospital, where doctors told him the infection had spread. Within hours he was paralyzed from the waist down.

Graves’ paralysis left him in a wheelchair and turned him into what he called a “reluctant healthcare expert.” He and his firm began designing wheelchairs, furniture for hospitals and even hospitals themselves.

“I want to do as much healthcare as I can before I croak,” Graves said in a lecture last year.

Graves’ death comes as young architects are showing a new interest in the origins of postmodernism. Many of the most outspoken advocates for saving the Portland Building have been young designers.

Architecture today is as eclectic, as devoid of certainty, as the period in the 1970s when Graves and postmodernism emerged. Periods like that always produce a new interest in history, in basics and fundamentals; this one is no different. As a result, both Graves’ designs themselves and their historicist bent have begun to look fresh to designers, architects, critics and curators in their 20s and 30s, many of them raised on a steady diet of flat-roofed, Dwell-magazine style neomodernism, which now can look conservative or dull.

In 2011 the Victoria and Albert Museum mounted a major retrospective on postmodernism in design, music and fashion. Adrian Searle, reviewing the show for the Guardian in London, said that the many kettles in the show, including Graves’, summed up the design movement better than photographs of any building could.

Postmodernism, Searle wrote, was “an epoch in a teapot.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.