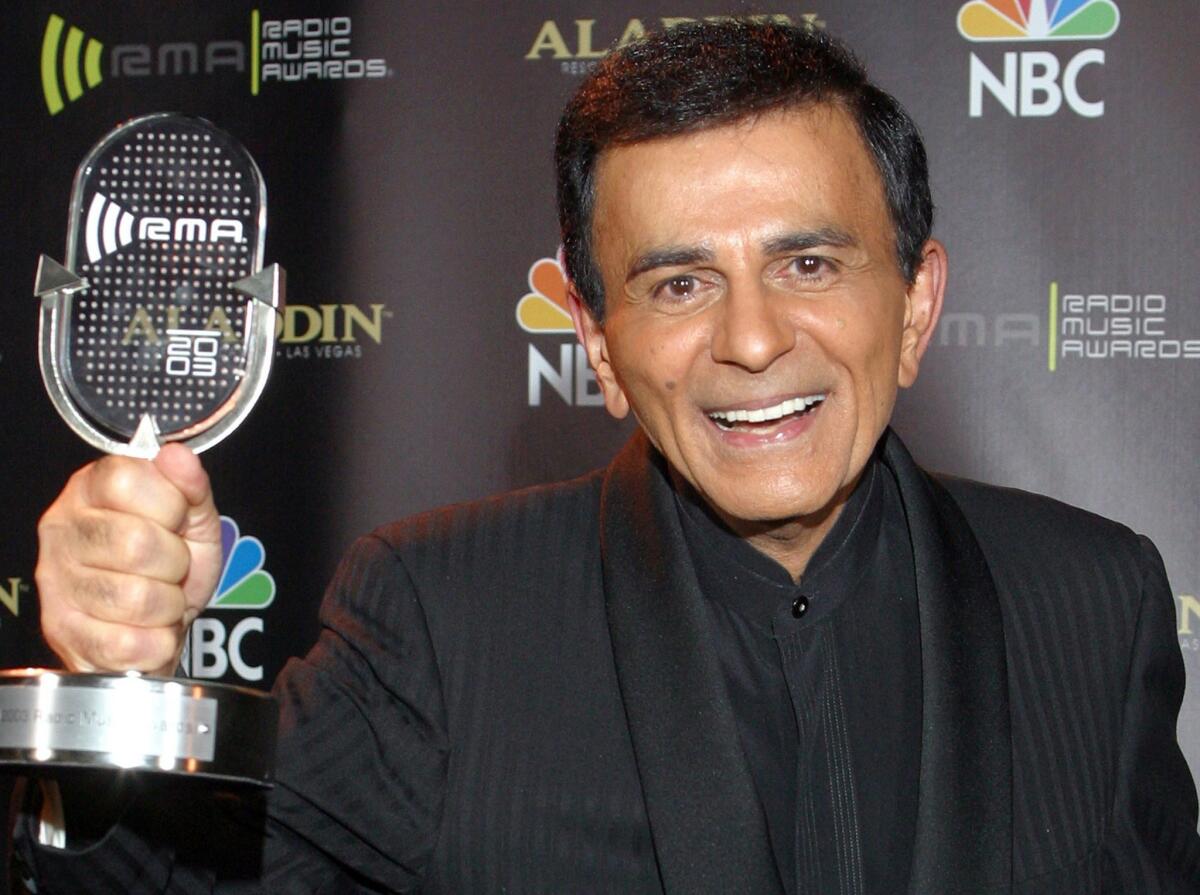

Casey Kasem dies at 82; radio personality hosted Top 40 countdown show

- Share via

For decades, he was among the nation’s best-known — and ubiquitous — radio personalities, hosting the weekend Top 40 programs that carried him “from coast to coast” and into the homes of millions of listeners eager to find out which pop song had made it to No. 1.

Earnest, upbeat and just a little bit square, Casey Kasem counted down each week’s hit tunes, relating personal tidbits about the artists and honing his signature catch phrases — from his greeting (“Hello again, everybody!”) to his sign-off (“Keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars!”).

------------

FOR THE RECORD

June 15, 1:45 p.m.: An earlier version of this post said that Kasem arrived at Los Angeles’ KRLA radio station in 1964. He started there in 1963.

------------

The Los Angeles-based disc jockey pioneered the nationally syndicated countdown-style radio show in 1970 with “American Top 40.” As he hosted the popular program and its numerous spinoffs over the next four decades, his warm, distinctively husky tenor became one of the country’s most instantly recognizable voices.

Kasem, who also lent his voice to popular cartoon characters such as the teenage “Shaggy” on the long-running “Scooby-Doo” TV franchise, died Sunday at age 82, according to his daughter Kerri Kasem’s publicist, Danny Deraney.

Kasem, who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and a form of dementia, died at a hospital in Gig Harbor, Wash.

His death came after a highly publicized battle over his healthcare between his second wife, Jean, and the three adult children from his first marriage.

As he built a national radio audience, Kasem became a major force in American popular culture. His program, with its song lists, bits of trivia and nuggets of music history, all pre-recorded and sent out to stations on reel-to-reel tapes, was aired on the radio the same weekend in cities and rural communities across the country, creating a shared musical and cultural experience.

Ryan Seacrest, who took over Kasem’s “American Top 40” show in 2004, said Sunday that listeneing to Kasem’s show when he was a boy triggered his own “dream about someday becoming a radio DJ.”

“So when decades later I took over,” he said in a statement, “it was a surreal moment.”

In 2009, on the 39th anniversary of his first Top 40 program, Kasem quietly retired from his last shows, “American Top 20” and “American Top 10.”

“American Top 40,” which Kasem created with producer Don Bustany, premiered July 4, 1970 on a radio network of just seven stations. Modeled after the 1940s program “Your Hit Parade,” it eventually aired on more than 1,000 stations, including 400 on the Armed Forces Radio Network.

Based on Billboard magazine’s most popular singles from the previous week, the show featured the disc jockey’s biographical storytelling and listeners’ long-distance, often heart-tugging dedications, read on the air by Kasem.

The minutiae-laden, feel-good narratives between songs were grounded in his own Lebanese American background.

“I was drawing on the Arabic tradition of storytelling one-upmanship,” he told the New York Times in 1990. “When I was a kid, men would gather in my parents’ living room and tell tales and try to outdo each other. I couldn’t understand the language, but I was fascinated.... I was doing trivia before anyone was doing trivia.”

Kasem later said he knew the single-song format would win out over album radio. But his program’s longevity may have been due as much to his own regular-guy appeal as to the music he played, some observers said.

Kasem has “always transcended industry trends,” Time magazine said when the deejay stepped down in 2009. “He created American Top 40 in 1970 when the genre was said to be dying, and embraced corniness as Vietnam-era cynicism peaked.”

Kasem explained it this way. “I accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative,’ he said in the 1990 New York Times interview. “That is the timeless thing.”

Born April 27, 1932, in Detroit, Kamel Amin Kasem was the son of Lebanese Druze immigrants. His father ran a grocery store.

In high school, he began using “Casey” as his first name and was bitten by the radio bug when a teacher praised an announcement he made over the school’s public-announcement system.

A student at Wayne State University in Detroit, he was drafted into the Army in 1952 and sent to Korea, becoming a deejay for Armed Forces Radio during the Korean War.

In 1956, he graduated from Wayne State with a bachelor’s degree in speech and English.

After graduation, he briefly tried to make it as an actor in New York, then returned to Detroit to become a radio announcer. He landed disc jockey jobs in Cleveland, Buffalo and Oakland and in 1963 moved to KRLA radio in Los Angeles, partly to further his dreams of an acting career.

He hosted “Shebang,” a short-lived TV music program on KTLA-TV Channel 5 produced by Dick Clark, and appeared in such films as the 1971 horror flick “The Incredible Two-Headed Transplant” and as himself in others, including “Ghostbusters” in 1984.

Kasem forged yet another career in voiceovers for cartoons and an estimated 10,000 commercials. Along with his long-running role as Scooby-Doo’s slacker pal Shaggy (“Zoinks!”) starting in 1969, he voiced Robin “the Boy Wonder” on the animated “Adventures of Batman” in 1968 and had many other roles.

Although he was known for family-friendly radio, Kasem was also a perfectionist who could be tough on his staff. In a 1985 episode, caught on tape and widely circulated, he let loose with a string of expletives after his writers had him read what he felt was an embarrassing letter on the air about a dead dog named Snuggles.

He made light of the lapse in a 2009 Oakland Tribune interview. “I just blew up,” he said. “It was a bad day.”

In 1992, Kasem was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame.

For the past 30 years, Kasem was also politically active but kept that “flip side” of his life, as he called it, carefully separate from his radio persona. He spoke out frequently for Palestinian rights and Arab American causes and politicians. He protested U.S. military involvement in the Middle East, voiced concern about anti-Arab stereotyping and arranged conflict resolution workshops for Arab and Jewish Americans in Los Angeles and his native Detroit.

He said he was moved to activism on Mideast issues after Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon left thousands of Lebanese and Palestinians dead and injured. “All of a sudden, that was really close to home,” he told People magazine in 1990.

He also advocated on behalf of the homeless and for affordable housing, once sleeping overnight on a downtown L.A. sidewalk to draw attention to the plight of street people. He was a longtime vegan who supported animal rights and was an anti-nuclear activist.

Kasem’s first marriage to Linda Myers ended in divorce. In 1980, at a ceremony officiated by the Rev. Jesse Jackson, he married actress Jean Thompson, who had a recurring role on “Cheers.”

In 2013, Kasem’s adult children announced that he had advanced Parkinson’s disease and filed a petition in L.A. County Superior Court seeking temporary conservatorship, alleging they had been barred by Thompson from visiting their father. The parties later negotiated an agreement, but the dispute continued with more court action up to the last week of his life.

On Wednesday, a Los Angeles judge upheld Kasem’s health directive and ordered his caregivers to stop providing nutrition and hydration.

Survivors include his wife, their daughter, Liberty Irene; three children from his first marriage, Julie, Kerri and Mike; and his brother Mouner Kasem.

Some observers likened Kasem’s familiar, mainstream on-air persona to the radio equivalent of comfort food. He didn’t object, positing his own theory about his continuing popularity.

“A lot of people have grown up with me,” he said in a 1989 Times interview. “I’ve sort of become part of the family.”

Trounson is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.