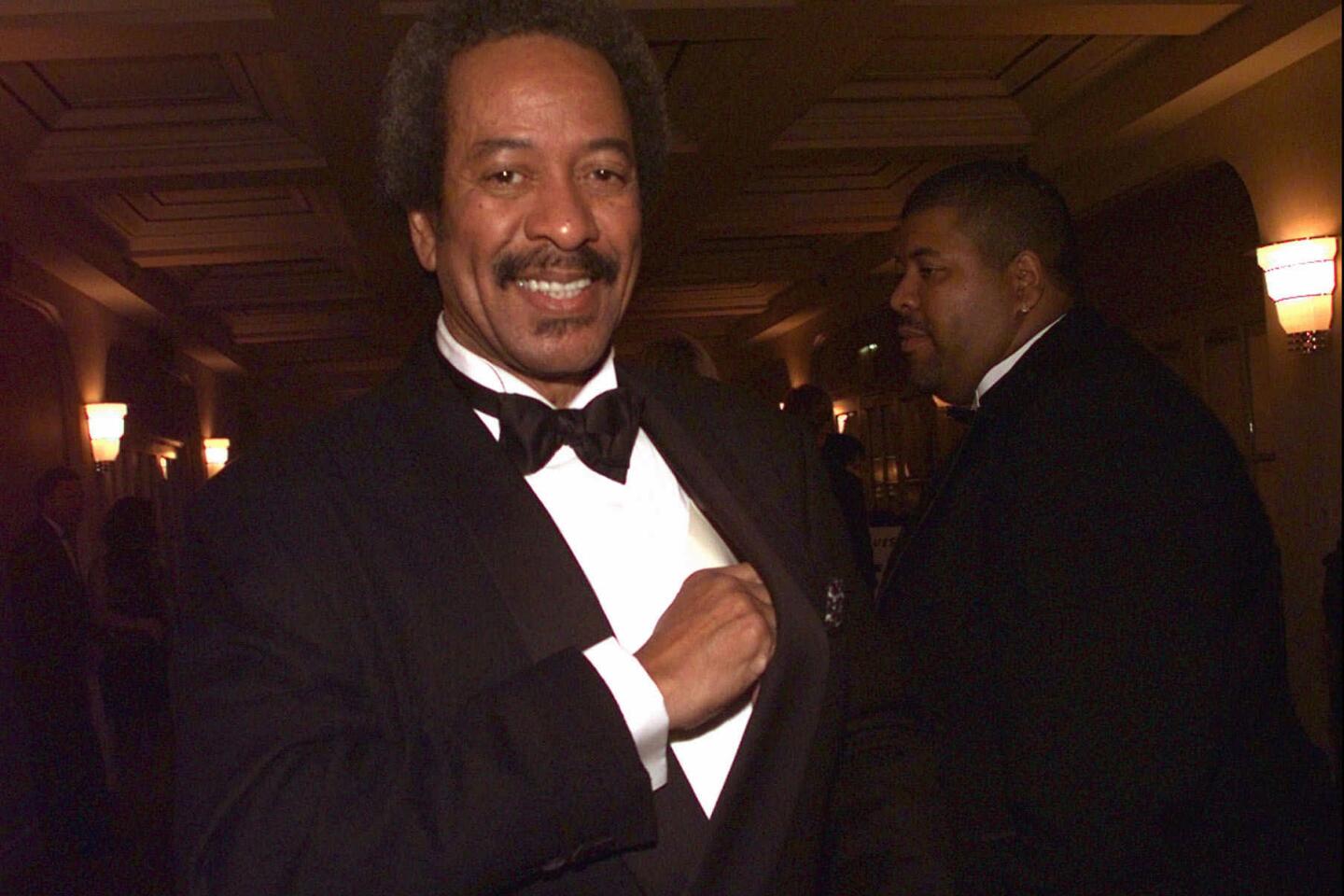

Allen Toussaint, legendary New Orleans musician, dies at 77

- Share via

Like tens of thousands of others driven from their New Orleans homes a decade ago, musician Allen Toussaint had to abandon his beloved hometown in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

Rather than expressing bitterness or anger at all he and others had lost, he remained buoyant. “I know that for anything this bad to happen, there has to be something just as good coming along to balance it out.”

The revered songwriter, producer, pianist and singer — who died Monday at 77 of a heart attack after a performance in Madrid — was a key architect of the early rock and R&B music that flowed from New Orleans to the national stage, an artist whose widespread influence led to his eventual status as a patriarch of the city’s fertile musical mash-up.

Toussaint had a hand in such hits as Benny Spellman’s (and later the Rolling Stones’ and Robert Plant and Alison Krauss’) “Fortune Teller,” Ernie K-Doe’s “Mother-in-Law,” Lee Dorsey’s “Ya-Ya” and “Working in the Coal Mine,” Irma Thomas’ “It’s Raining,” Al Hirt’s “Java,” Dr. John’s “Right Place, Wrong Time,” Glen Campbell’s “Southern Nights,” the Pointer Sisters’ “Yes We Can Can” and LaBelle’s disco hit “Lady Marmalade,” and in recent decades, his recordings have been sampled by a broad swath of hip-hop acts.

Paul McCartney, the Rolling Stones, Paul Simon, the Band, Fats Domino and Elvis Costello arrived at his door to borrow his signature touch as a producer on their own records. His songs were recorded by dozens, if not hundreds, of musicians.

Many of them quickly lionized Toussaint.

“One of the greatest songwriters New Orleans ever produced,” Rolling Stones guitarist and songwriter Keith Richards said in a statement after Toussaint’s death.

McCartney, who brought Toussaint in to work on his 1975 solo album “Venus and Mars,” posted a statement on his website calling him “a sweet and gentle guy.... His songs will be cherished by people like me who will have fond memories of Allen forever.”

Johnny Cash’s daughter, singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash, called his death “an irreplaceable loss.”

“It makes you wonder what rock ‘n’ roll would be without New Orleans, and what New Orleans music would be without Allen Toussaint,” Greg Harris, president of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, told The Times on Tuesday.

In fact, Toussaint was a key figure in restoring hope in the aftermath of Katrina. He teamed with Costello on the first major recording session to take place after the hurricane, recording the widely praised album “The River in Reverse,” which confronted the issues and emotions that welled up after the disaster.

He also performed at the first big musical event after the hurricane: the 2006 edition of the annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. And 13 months after Katrina, he and New Orleans singer Irma Thomas were invited by producer Ken Ehrlich to sing the national anthem at the first NFL game to be played in the renovated Superdome, which had served as an emergency shelter for thousands of displaced residents.

Ehrlich on Tuesday recalled lobbying for Toussaint and Thomas to handle “The Star-Spangled Banner” even though network executives at ESPN had pushed for an internationally recognized pop superstar.

“You have to realize the emotion of that moment,” Ehrlich said. “People were filing into a place they hadn’t been in almost a year and a half, a place that was such a symbol of Katrina. The roof had fallen in. It was an incredibly emotional moment, and the first thing they heard was Allen and Irma. That was it. It was like, ‘Yes, we’re home.’”

Allen Richard Toussaint was born Jan. 14, 1938, in New Orleans. He was drawn to the piano as early as the age of 6, after his aunt sent an old upright to his family’s house for his sister to study on.

------------

For the Record

Nov. 12, 4:32 p.m.: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Toussaint was born in 1937. He was born in 1938.

------------

The boy quickly made sense of the instrument and began to experiment with everything from Ray Charles to the flamboyant quasi-classical piano music of Liberace. But it was the freewheeling, rolling keyboard style of New Orleans piano master Roy Byrd, a.k.a. Professor Longhair, that inspired him most.

“That just shocked me, to hear the piano go like that,” Toussaint once told Keyboard magazine. “Professor Longhair had another reason and rhyme for everything. His language, his speed of operation, his mobility — everything was just totally different.”

Producer Dave Bartholomew, best known for multiple million-selling hits with Fats Domino, asked Toussaint to sit in on some of Domino’s recording sessions in the late 1950s.

Toussaint’s first album, “The Wild Sound of New Orleans,” did not yield any national hits for him but established his reputation as a formidable pianist and songwriter. It also included two important instrumentals: “Java,” which New Orleans trumpeter Al Hirt turned into Top 5 hit in 1964, and “Whipped Cream,” which another trumpeter, Herb Alpert, did with his group the Tijuana Brass. “Whipped Cream” eventually became the theme song for the TV show “The Dating Game.”

In the 1960s, Toussaint’s multifaceted talent came into play as he wrote, arranged, produced and performed on scores of recording sessions by New Orleans artists.

“He was like a one-man Motown,” said Quint Davis, producer of the New Orleans jazz festival, where Toussaint’s performances were an annual highlight.

“His greatest contribution was in not allowing the city’s old-school R&B traditions to die out … by keeping pace with developments in the rapidly evolving worlds of soul and funk,” states Toussaint’s biography at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

In 1971, the Band’s Robbie Robertson enlisted Toussaint to assemble a horn section to accompany the group for a series of year-end shows, from which the group’s Top 10 live album, “Rock of Ages,” emerged. A quarter century later, Robertson gave the induction speech when Toussaint was elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The work with other musicians often meant he had little time to make records of his own.

Yet the title song of one of his recordings, “Southern Nights,” caught the attention of celebrated songwriter Jimmy Webb, who had written many of Glen Campbell’s career-making hits. He suggested the singer-guitarist-TV show host record it, and it gave Campbell a No. 1 hit.

Campbell’s sprightly version had a different feel than the liquid gentility of the original, which became Toussaint’s signature song. Often in concert Toussaint would stretch the song out for 10 or 15 minutes, sharing stories of his childhood in New Orleans, regaling audiences with his seductive, honeysuckle voice and incorporating old jazz standards and classical piano pieces with his own music.

“I was in Memphis the day that Elvis died,’ said Davis, the jazz festival producer. “It was like biblical Passover, like somebody in everybody’s family there had died, everybody felt it personally. I think on the New Orleans scale it’s a little like that.

“A part of everybody here is lost.”

Toussaint is survived by his wife, Sandra, and children Alison and Clarence “Reggae” Toussaint.

MORE OBITUARIES:

Helmut Schimdt dies at 96; W. German chancellor fought domestic terror

Gunnar Hansen dies at 68; played Leatherface in ‘Texas Chain Saw Massacre’

Howard Green dies at 90; Harvard scientist developed technique for regenerating human skin

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.